By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – One of the nicest things that one can do for other people is to remember their names, especially after they have died. Just by saying or writing people’s names is to testify to their existence, to the fact that, as individuals, they walked the face of the earth and that their time here mattered.

The San Diego Museum of Man, in its permanent exhibition about the lives of the indigenous Kumeyaay people, paints a picture in text and artifacts about where the Kumeyaay lived, the foods they ate in different climate zones, their patterns of trade and military alliances, their life cycle stages, their gender roles and occupations, their art and their entertainment. It is a comprehensive exhibit from which students can learn much simply by reading the panels.

The exhibit is enlivened by photographic peeks into the lives of such Kumeyaay as the shaman Cinon Mataweer, the potter Wass Hilmawa, the ritual dancer Manuel Lachapa, and the basketmaker Carmalita La Chappa.

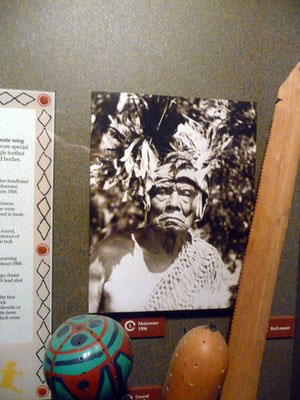

Pictured in 1906 in ceremonial costume in an exhibit case that also includes gourds and an instrument known as a bull-roarer, the visage of Cinon Mataweer attracts the attention of passersby. What is this old man doing here?

The answer is provided in a panel that says “ceremonies and dances were marked by elaborate song cycles, accompanied by rattles. Ritual leaders wore special costume, including feather head plumes and eagle feather skirts, and all participants painted their faces and bodies.”

In the photograph, Mataweer “wears the traditional headband and owl feather plumes of a Kumeyaay kuseyaay (shaman) along with an eagle feather skirt worn as a bandoleer.”

As for the gourds, they were “obtained in trade” and were commonly used in the ceremonies. “The bull-roarer, whirled to make a loud humming sound, announced ceremonies, and was hung over the entrance of ceremonial enclosure to guard its contents.”

The museum legend also reported that the “bullroarer is from Capitan Grande, 1908,” which today is under the lake created by the construction of the El Capitan Reservoir. For the most part, the Kumeyaay who lived there moved to an area near Lakeside known today as the Barona Indian Reservation.

Manuel Lachapa is shown dancing the “whirling dance” in 1910 at Mesa Grande, which is a Kumeyaay village in the Cleveland National Forest.

The exhibit tells visitors that “shamans were individuals who had the ability to make contact with the spirit world through trance states and dreams, gaining supernatural power to use for the benefit of the people. The Kumeyaay had many shamans. Some had power over the weather, others over big game, finding lost objects, curing rattlesnake bites or bringing good crops.

“In early historic times the Kumeyaay received from the north a new religion centered on the use of toloache, a vision-producing plant. The toloache religion superseded many older beliefs – it is probable that many characteristic ceremonies, including the whirling dance with its eagle feather skirt, were introduced at this time. “ With the eagle feather skirt (shown in the exhibit), the dancer could “imitate an eagle’s flight.

A series of photographs show Wass Hilmawa demonstrating the Kumeyaay methods for making pottery in 1928. It was a process that required skill and patience, according to the storyboard.

The clay was dug out with digging sticks, dried, pulverized, sifted, and kneaded with Yerba Santa leaves. Thereafter, “the base of a vessel is begun on the bottom of an old pot rubbed with ashes. Thinning is done by paddling. New clay is rolled between the palms into long coils and bonded to the unfinished pot by pinching. The vessel is turned upright and a small anvil is held inside to support the wall while the paddling continues. The anvil may be a small pot, a cobble, a mano or a specially made clay anvil.”

Once the pottery is put into final shape, it is smoothed with wet hands, sun dried, and painted with red ochre. Often a broken piece of pottery would serve as the paint palate. After more drying, the pot is fired in an open kiln using oak bark. “Potters state that the pots will break if anyone watches the firing.”

Basketry was another art at which the Kumeyaay excelled, with weavers making “effective use of their environment as a source of varied raw materials.,” the exhibit states. Among favored materials is juncus, which grows in marshes.

“The stems are split into 3 or 4 pieces. Color gradation on the stem gives a variegated appearance to the basket,” the exhibit panel informs. “Split juncus was dyed black for basketry designs. The pulverized acorn caps of Canyon Oak contain tanning which reacts with iron in water from certain springs to produce the black dye.”

The slide show below this article includes a basket with deer motif that was made in Campo, approximately in 1900. The deer was created with dyed juncus. Also shown is a larged coiled tray, featuring a rattlesnake design in dyed juncus that was created between 1932 and 1942 by Carmalita La Chappa in Campo. A photograph of her holding the tray is included in the exhibit.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World, a publication covering San Diego, the Jewish community and the world.