By Sam Litvin

SAN DIEGO–I’m home, far from the weary roads of travels. But as I listen to the new CD by Damike and Bete-Avraham, the beats transport me far away, far off to Africa more than a year ago..

SAN DIEGO–I’m home, far from the weary roads of travels. But as I listen to the new CD by Damike and Bete-Avraham, the beats transport me far away, far off to Africa more than a year ago..

I remember how on the flight over there, the plane broke through the thick, gray blanket of clouds and a green carpet lay below. The houses and cars bellow the wings were like the cars I would imagine when I was a child, sitting in bed, driving them through the curves of the orange wool blanket covering my legs.

“It’s a lot greener than I expected.” I said to Claudia, intern to the Italian Embassy, who was on her way from Bologne to Nairobi. Her thin, straight features beneath the black frames fascinated me as much as the hemp pants and blue tank top covering an elegant form.

Coming out of the plane into the main airport a large expansive window uncovered a view to a gray Addis-Ababa. The airport was white with marble yet with an air of a lack of refinement. There was no internet and I had no phone. A worker let me call my couch surfing host after I tipped him a few burr. I bought a glass of tea and as I waited for Tesfah. Suddenly a spasm gripped my stomach. I walked quickly back to the bar and asked for a shot of vodka. Bartender placed a hazy glass half filled with clear liquid. I gulped down glass and felt the heat of the alcohol go down my esophagus and extinguish the spasms like water on a fire.

As relief came over me, an older British man came up to me to ask if I was alright. I must have looked odd being the only Westerner in the airport. Peter was an aid worker and had apparently missed the family he was supposed to pick up. His wife is a founder of schools in Addis and he was a travel writer for Lonely Planet. He waited with me until Tesfah got there with a paper and my name in big capital letters. I always wanted someone to pick me up from the airport with a sign. We got into Peter’s old Toyota pickup, worth a fortune here, and headed towards Bole where Tesfah lives. We drove slowly through potholes, past women in colorful tunics and men herding goats, past self made sheds of Addis, around the Bob Marley roundabout where steel wires await their statue of the Rasta. Rastafari culture, Tesfah tells me, was invented in Ethiopia, and colonies of Rastas live in the south. Arriving, we walked past people buying roosters for the New Year, to the compound, a small home painted blue bordered by a fence with glass shards at the top and a crescent and star on the gate.

“I rent from Muslims,” Tesfah told me. Inside were women covered in colorful tunics, little girl of about two walking around in cute little dress. In his home, you had to walk down a corridor past the communal toilet and shower, a modernized version of an outhouse. Inside their one bedroom apartment walls were painted light blue like my childhood room, in the living room was a nice flat screen TV in the corner, a portable electric stove by the entrance on a cupboard, a coffee table and two sofa chairs. The other room had one window, a bookshelf against one wall and a dresser against the other. Besides the books on the bookshelf, there was a picture of Barack Obama. The bed was against another wall and there was a mattress on the floor. On the wall in pink was a drawn outline of Tesfah’s girlfriend. Tesfah seemed proud and embarrassed about it at the same time.

His roommate, an engineer and I sat down with Tesfah for a meal. The made ingera (a soft flatbread made out of a seed of a plant called Teff, used in place of utensils) and lentils and spoke about God and religion and then I took my rest.

I woke up from my nap and walked into the living room. Tesfah was reading on a sofa chair. I dressed slowly and we took off on a long road, going from taxi bus to taxi bus across Addis to the Jewish ghetto, the village of Kechene. As we drove, posters and pictures of Ethiopia’s President were everywhere, as was the slogan “Yes We Can.” He died only a day or two before I arrived but the country did not seem to be in too much mourning. “He was a dictator.” Tesfah smirked.

We arrived into the village to throngs of crowds walking the streets, cars moving slower than people navigating the rough human waters. The village was a brown place beneath the haze of smog that envelops the hills of Addis. The brown huts were divided by wide brown paths. Kids were everywhere, they ran around and ran after me saying “Hello! What’s your name!?” One, about age eight, stood in front of me on one leg smiling in a Yoga stance. We asked for a synagogue at an intersection and we were directed in two perpendicular directions. We took the straight path and I after a couple blocks, I saw it.

The Synagogue was on a windy and narrow cobblestone road. On the side of the road were deep trenches and front doors of every home had a mini draw bridge. Behind a metal fence, the synagogue was just a small building marked by a spire with a three-dimensional star of David composed of two pyramids in front of the building. Tesfah and I went inside. It was a small room, maybe 5 by 10 meters with a large carpet on the floor and dark red upholstered seats set up in a U-shape facing the wood-paneled Ark. In front of it was a small short table with food, candles and a glass of wine. Four men wearing jackets in varying shades of brown sat in front of me. “Hi, I am from California. Can I take pictures?”

“It’s Shabbat.” One of the men answered.

“What time does it start?”

“Eight” He replies

“So can I take pictures?”

“Candles are lit.” Said the man in a red jacket and a white eye. I took that as a no. Another man walked in; curly haired wearing dark rimmed glasses, it was Samuel or Sintayehu. I told him about my project. He smiled and said “May Hashem guide you and your project.” He told me that this is the first official Synagogue, earlier they rented space for Shabbat. They have one school for the entire ghetto. There are 80,000 people living there and for all intents and purposes, abandoned by the government, even more than usual for Ethiopians.

It was time to start. They read the siddur in Amharic, the language of the region. After prayers from the siddur, one by one they read from the Torah in Hebrew and what seemed to be Amharic as well, or maybe it was just their accent. When they sang in Amharic, the poetic rhythm seemed to match the rhythm of Hebrew. They finished Shabbat prayers with an Ethiopian song of Shabbat and a song for Jerusalem. The singer or cantor was Demeke. His voice took on inflections of Amharic, coloring old Jewish songs. After songs, they brought out the Ethiopian Challah and we each ripped off a piece. It was a thick pita-like bread the size of a large pizza, covered in olive oil and sesame seeds.

As we ate and I talked about my project, a black woman with a French accent came in. She was a Togan, living in France and had converted to Judaism. Her name was Rachel and her sister had been to the community before and asked Rachel to bring an Israeli flag that she got in Israel for the Shul. The young men unrolled the flag and held it beneath their chin looking down, their faces beamed with smiles. The woman was a UN political analyst here in Addis. As we left, Rachel offered us a ride home. As we drove, I learned of her work as well as a bit more about Samuel, the engineer and community activis.

Two days later, we came back to the Synagogue, this time with Peter, the aid worker. At the synagogue we met with Sintayehu again. We sat and quietly listened to their tale of the Ethiopian Jews.

The inhabitants of Kechene are the Bete-Avraham, they are the original Jewish community of Addis-Ababa, having been in Addis since the end of the Jewish Kingdom in north Ethiopia. The kingdom began when Jewish traders made their way from Yemen. They slowly captured more and more land and as they multiplied and converted their slaves, they soon had a large kingdom in the North. For nearly a thousand years they lived with the Christians until the 1400’s when Arab Muslim armies began to invade. They joined the invaders in a battle against their Christian neighbors, but the gamble did not pay off and they lost. Angered by their switch of allegiance, Christians destroyed the Jewish empire, dispersing the Jews as they were dispersed from Israel.

Some Jews stayed in the mountains of the north, while the Jews of Bete-Avraham escaped heading south, rather than remain living in an area where they would face constant war. They instead chose the capital where for hundreds of years, they would be forced to pretend to be Christian. Like conversos of Spain, they practiced mostly in secret, inside clandestine synagogues. They worked in crafts and blacksmithing. Sintayehu told us that in the community, there are no beggars, and the elderly and orphans are cared for by the community through a fund. According to him, there are two messianic and two pre-talmudic synagogues in the area. The main synagogue is the only one which practices in open, but for that reason, they have a small following. Others, too afraid, choose to practice in secret in the fifteen secret synagogues. This fear comes from the government’s repression, loss of jobs, loss of schooling and sometimes, even loss of burial rights. There are very few synagogues today due to the high conversion rates. As Israel focused on the North, the south faced increasing numbers of evangelists. As a sign of their dwindling numbers, twenty years ago there were 44 synagogues and today, there are none, all shut down by the Church.

However, Synagogue or not, on Saturdays, the entire village rests, just as they have for thousands of years. These are not the Falash Mura, the converts; what I felt was that these Jews are the Bet Israel, the forgotten ones.

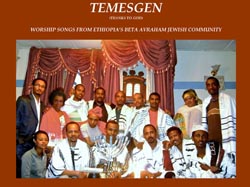

Today, as they struggle for their independence, they fight not with sticks and stones, but with music. They just released an album that is truly something. You can feel their hope, their sorrow and their fight as well as the mix of Hebrew and the Ethiopian rhythms. It is things like these that remind me what a special global community of people I am part of.

You can purchase the CD on Amazon for $8.99.

For more information about Bete-Avraham and Kechene village as well as how you can support the people there, go to http://www.enszo.org/ or follow them on their facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/groups/infoenszo/

*

Sam Litvin, originally from Ukraine, is a traveler, writer, photographer and engineer living in San Diego. His articles may be found on the website “Sam the Jewish Guy”

Beautifully written! Congrats on a job well done

Mr Litvin:

A small research would go a long way.

You wrote: ”Bete-Avraham, …, having been in Addis since the end of the Jewish Kingdom in north Ethiopia”

There hasn’t been no Jews in Addis for hundreds of years. Simply because there was no capital city called Addis Ababa for hundreds of years. Addis was only 120 years old. And that would have given you some clues as to the authenticity of their claim.

Besides, “Bete-Avraham” are from north Shawa, and shaw has been an independent kingdom since 16th century, until the time of King Theodor in the 19th century. So making hard any effort to link them to northern Ethiopia Jewish kingdom.

On the Jewish kingdom in Ethiopia itself, I have a few things to say. Just because you can’t find the facts about the origin of Jews in Ethiopia doesn’t mean you have to invent one. For sure your story about Yemen Jewish and their Slaves makes me laugh. It is typical among white skinned people to believe in their own myth, where whites own blacks as Slaves, never any other way. Well, as a Ukrainian you should have known this better, as a Slav. Which to this day declares your humble origins as properties of the Romans.

The truth is, the only mass arrival of Yemeni Jewish to Ethiopia happened in the 6th century, when the kingdom of Dha Nuwas was destroyed by Ethiopians. Many of the survivors were sold in to slavery and many, no doubt, were brought back to Ethiopia as domestic slaves or food soldiers. We don’t know if their descendants survived or not, but centuries latter, we would here of a people who profess Jewish faith.

Thank you Rahel for your kind words.

Knox, while I did due research into the Bete-Avraham, Ethiopia and Bete-Israel, I am not a historian by profession and thus much history is naturally unknown to me so please forgive me for any errors. I simply relay what I learned while I traveled. While your comments make me ponder and want to look more into the claims, your arrogance makes me doubt them and your insults even more so.

Thank you kindly,

Sam Litvin

To address your claims Mr. Knox.

While the city was chartered in 1886, it had been settled since ninth century.

Jews have been in the area since 1400’s although maybe not in the city itself but in the area. Currently most live in the city as Jewish people often tend to concentrate in urban areas.

-James Quirin, The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews, p. 48

A trailer for a documentary by Irene Orleansky who went to record the Beta Avraham only a couple months before I went there shows the community and their struggle.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=qtHsRUnLxK0