-Thirteenth in a series-

By Donald H. Harrison

BUTTE, Montana – In this old west city where the very first mayor was Jewish, Montana’s oldest synagogue may be on the verge of dying. Meanwhile, at the city’s annual Montana Folk Festival, the klezmer music of Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews is periodically reincarnated.

Thus summer visitors were able to experience mental snapshots of Jewish life in the 150 years since Montana Territory was created in 1864, a quarter-century before Montana became the U.S.A.’s 41st state.

The brick home of Henry Jacobs is a landmark in downtown Butte’s historic district. A native of Baden, Germany, he served as mayor from 1879 to 1880, having also won distinction as a school trustee and as president of the Hebrew Benevolent Association.

Jacobs and his wife Adele were in the shmata business, having established the H. Jacobs and Company clothing store in 1876. Jacobs, who was a Confederate Army veteran who survived the siege at Vicksburg, Mississippi, also served as president of the local chapter of the International Order of Foresters.

According to local historian Richard I. Gibson, stucco has been applied over the bricks and a vintage wrap-around porch was not part of the original architecture.

The City of Butte treasures its historic architecture which is one reason that Pam Duncan Rudolph is confident that whatever happens to the tiny and aging Jewish congregation that occupies the distinctive Temple B’nai Israel building, the edifice itself will be protected as a national historic landmark.

Like other structures of the period, the synagogue was built in 1903 in brick, which, along with stone, was a mandated building material after a devastating fire in 1879 burned down many of Butte’s wooden structures in the central business district.

A Reform congregation, Temple B’nai Israel was initially one of three Jewish houses of worship—the other two being Orthodox—in a city where copper mining brought such economic prosperity that shortly after World War I, Butte was considered one of the richest cities in America. Copper had numerous uses, from pennies to bullets, and the miners who dug the metal out of the mountains surrounding Butte in turn needed to buy clothes, furniture and other goods, which attracted other Jewish merchants.

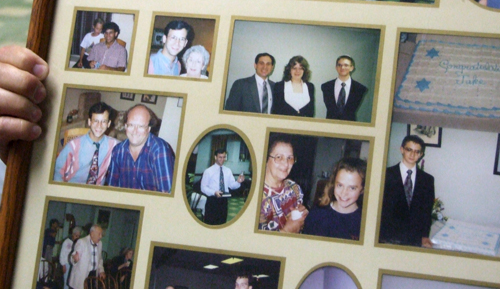

Among them was Kalman Rudolph, who two years after arriving in Butte, opened a junk business in 1919 that evolved into Rudolph’s Furniture that today, 95 years later, boasts a 28,000-square-foot show room and a 7, 000-square-foot warehouse. Kalman’s son Lewis, born in 1922, became the next operator of the business, and Lewis’s son, Michael, is the current owner. But whether the business will survive to the fourth generation is an open question, says Michael. His and Pam’s son, Max, helps out at the store, but “he’s not interested. He is passing time, while he goes to school,” said the father.

In the 1930s, the Jewish community of Butte was large enough to host a large regional convention of the B’nai B’rith, but as the copper industry switched from deep hole mining to strip mining, desecrating the environment in the process, jobs began to dry up, and the economy began to change.

Many Jews moved away in search of better economic opportunities, and this was reflected by the fact that the three Jewish congregations eventually were consolidated into one. By 1968, when Michael Rudolph, was scheduled to have his bar mitzvah, the last full-time rabbi had moved away from Butte because the congregation could no longer afford to pay him. Michael had a lay-led ceremony.

Since then, services have been lay-led, and they have become fewer and fewer in frequency. Unable to sustain weekly Shabbat services, the congregation now holds High Holiday services and some other occasional celebrations, including a gala weekend in 2003 marking Temple B’nai Israel’s centennial.

Temple B’nai Israel today has the distinction of being the oldest temple or synagogue in continuous use in Montana. However, Pam Rudolph, a former president of the Temple who still serves on its board, doesn’t see a very long time horizon for the congregation, perhaps no more than 10-15 years, unless some unforeseen positive development once again swells its membership rolls.

“There are so few of us,” she explains. “I think we are now down to 14 family units and that includes my in-laws who are in their 90’s. During the High Holy Days, a good turnout for us might be 35 people.”

Since 1968, student rabbis have been imported from the Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles to lead High Holy Day services. Of interest to San Diegans, one of those rabbis was Scott Meltzer, who today is spiritual leader of the Conservative congregation, Ohr Shalom Synagogue, in the former Temple Beth Israel building at 3rd and Laurel Streets in San Diego.

Mike Rudolph grins at the mention of Rabbi Meltzer, who clearly was a favorite visiting rabbi. “He did have a way of going on long in his sermons,” Mike confided. “I always gave him a bad time, urging him to keep the Friday night services to an hour. He said ‘I always do’ and I said ‘no you don’t.’ One night I snuck up on the pulpit and put an alarm clock up there, set for an hour. He wasn’t even close to finishing when it went off, and he said, ‘you got me!’ He was in Butte not so long ago for a funeral, and he said, ‘I still remember that, it was the funniest thing.’”

Pam Duncan Rudolph said she grew up Christian, but became familiar with the temple at an early age because a girlfriend was Jewish. Little did she know that someday she herself would convert to Judaism and eventually be called upon to participate in interfaith discussions on behalf of the dwindling Jewish community or to be among the congregational leaders who worry how the temple can be preserved after the congregation can no longer be sustained. She said various options are under consideration, including selling the building to a church, or having it converted into a museum.

We noted in our conversation that Chabad had established outposts in other Montana cities, and perhaps would be interested in having a shaliach rebuild the Jewish community in Butte.

By fortuitous circumstance, grandson Shor and I came to Butte during the July 11-13 Montana Folk Festival. Several stages were erected through the city, and folk music of every description competed for attendees’ attention. But there was no question which performance Shor and I wanted to see. Alicia Svigals, formerly of the Klezmatics, was performing with her new group, the Klezmer Express, and I was anxious to see how the rhythms and Yiddish lyrics would go over in this land of cowboy hats and baseball caps.

We were barely into the concert featuring Svigals on violin, Patrick Farrell on accordion, Brian Glassman on bass and Steve Weintraub as the leader of crowd-participating horas and other dances, then the crowd was whistling, stomping and cheering to the rhythm of “Chittibim, Chittibum,”a Yiddish folk song about a hapless rabbi, who gets drenched in a storm while his followers stay dry. “It was written by non-religious Jews,” Svigals explained.

Another crowd pleaser was “Oy Tata” which Svigals said “means ‘oh daddy’ and in klezmer language when we sing ‘oh daddy,’ we’re talking about the daddy way above. So, for those of you so inclined , you may sing along ‘oy, mama’ or if you want to be gender-neutral you can just sing ‘oy yo.’

Weintraub, who often performs with Svigals, invited members of the audience to come up to the front of the tent to dance with him, and, he said later, “people go where the fun is. This is about dancing as a community, this is about seeing each other having fun. Considering that these were wedding dances in Europe and people often married outside of their community, you had two families who had to meet each other, so these dances fulfilled that.”

Betsy Miller, visiting from Orlando, Florida, was impressed by the positive energy. “I thought they were awesome getting all those people up dancing, all unified,” she said. “It was a beautiful thing.”

Roy Curet of Missoula had heard Svigals former group, the Klezmatics, play in Missoula, Montana, and drove over to Butte for the day to hear klezmer and other varieties of folk music again. Susan and Greg Morgan of Missoula accompanied him, with Susan commenting: “We are a very supportive folk music community in Montana. Music from all over gets tremendous receptions.”

The Manhattan-based Svigals, whose performance was arranged by the National Council for the Traditional Arts, said she enjoyed the enthusiasm of the Butte crowd. “I loved them, wanted to give each of them a big hug, they were so great,” she enthused.

“These are people who respond to music, clearly, and I have been going around to the various shows and they have been whooping it up, and what a great audience – awesome!”

She now is looking forward to playing at the Ashkenaz Festival in Toronto, where she will perform a score that she wrote for a silent film.

I couldn’t resist asking her if she knew Yale Strom, the klezmer musician and documentary film maker, who is an artist in residence with San Diego State University’s Judaic Studies Department.

She said she knew Yale and his wife, Elizabeth Schwartz, very well. “They are my buddies. I love Yale and Elizabeth. They are my homeys,” she said.

About San Diego, she said, “I would like Yale to hook up a gig for me!”

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IF YOU GO: We stayed at the Best Western Plus Butte Plaza Inn at 2900 Harrison Avenue, which provided free shuttle service to the Montana Folk Festival. Rate also included wi-fi, cable television, breakfast, and use of the indoor swimming pool. Next door is Perkins Restaurant, which offers hotel guests a discount on meals.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Love the article! It was such a pleasure to meet you and share our history. Come back again soon!

Very interesting article, Don.

I just got home from Montana. I went by the Temple several times. So happy to see all the fine articles. I want to be a member, even if I only come up 2x yr. thanks to all the members. My best to Nancy and Pam.

My grand parents lived in Butte with the Stoll family(Stolpensky) from 1914 until 1932 or 33

Kalman Rudolph was my grandfathers brother(Louis) brother-in-law. My grandfather and his brother

Louis had used furniture store(Stolpensky Brothers)

David Stoll

73 Old Course Dr.

Newport Beach, Ca. 92660

949 719 9636