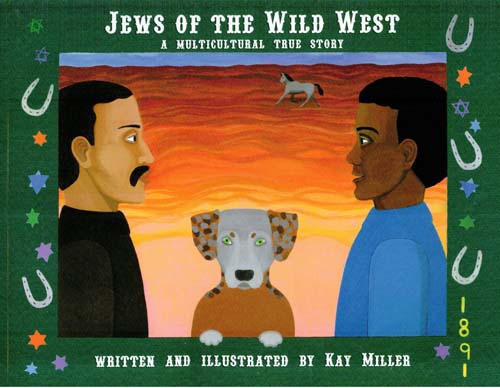

Jews in the Wild West, written and illustrated by Kay Miller; Paint Horse Press © 2012, ISBN 978-0-615-55388-7; 29 pages, $9.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—Although this book for juvenile readers was published in 2012, I know from lecturing about Jews in the West that the story it tells so very well is hardly known in the Jewish community, much less inthe larger general community. So it is worth sharing and dwelling upon.

In writing about the experiences of two great merchant families of New Mexico—the Staabs and the Ilfelds—Miller relates stories that vary considerably from what many consider to be the template of Jewish experience in America — immigration, struggle, and exploitation in the sweatshops and factories of the East Coast.

Miller explains for a young audience, both through her words and her illustrations, how people who owned general stores –selling all kinds of goods in sparsely populated areas—often prospered, expanded, became involved in civic affairs, in banking, and in some cases politics.

Abraham Staab’s general store catered to the needs of the people in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He became president of the Santa Fe Chamber of Commerce. He and his wife Julia built a mansion on Palace Avenue that became a social gathering place. Their guests included U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, and Rev. Jean-Baptiste Lamy, the first archbishop of New Mexico. Among his wife Julia’s friends was a nun, Sister Blandina, whose presence with her on a stage coach very possibly may have saved her life, and certainly part of her fortune. The stagecoach was held up by none other than Billy the Kid, a mean desperado. But after realizing that Sister Blandina was one of the passengers, Billy didn’t bother them – remembering the Sister’s kindness to him in the past.

Julia’s storied life had an unhappy ending. After one child died in a third-floor fire, Julia became depressed, withdrawn, and eventually she died of heartbreak at age 52. Some say that Julia’s ghost is still there at the mansion, anguishing for her lost child.

Abraham and Julia had a daughter, Bertha, who on one occasion went with the territorial governor, Herman James Hagerman, to visit the Hopi Indians, where they witnessed the Hopi performing a snake dance, which was their prayer for rain. Bertha married Max Nordhaus, and their son, Robert, grew up to be an athlete, skier, and rock climber –skills that served him well during World War II while fighting the Nazis in the mountains of Europe. Later Robert became an attorney and represented the Jicarilla Apaches before the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote the opinion finding for the Jicarilla against oil companies that wanted to drill on their lands without paying for the rights. With a partner, Ben Abruzzo, Robert developed the Sandia Peak Ski Slopes in 1960, constructing a tramway that climbs 4,000 feet up Sandia Mountain.

Anna was another daughter of Abraham and Julia Staab. She married Louis Ilfeld, thus uniting the two Jewish merchant families. The Ilfelds had made their fortune in Las Vegas, New Mexico.

Louis’ uncle, Charles ilfeld, had traveled by ship from Germany to New York, and then by train, ferry, and ox wagon to Santa Fe to join his brother Herman in the general store. Eventually Charles knew the business well enough to start his own general store in Las Vegas. That required transporting pots, pans, kerosene lamps, and various other products to Las Vegas on the backs of 75 mules. Initially, Charles slept under the counter of the Las Vegas store to protect it from robbers. But he gradually prospered, and eventually built a large building that became known as Ilfelds on the Plaza. Today, the space is occupied by the Plaza Hotel, but some of Ludwig’s goods are still displayed there.

Among Charles’ friends was Montgomery Bell, a freed slave, whom he initially employed to manage the stables, and who later became an agent for the company. Eventually Montgomery started his own business, prospered, and built one of the first two-story buildings in Santa Fe.

Louis’s brother, Ludwig, tried his hand at many jobs. He sold bicycles, worked as a fire chief, owned a hardware store, started a radio, and a ranch. Along the way, he met Theodore Roosevelt, who loved to go exploring in the West. Ludwig attended Roosevelt’s inauguration. He also was a lay leader of the Montefiore Synagogue in Las Vegas, which was the first Jewish house of worship in New Mexico. When the rabbi was away, he knew how to lead Shabbat services.

So what is it that this story about the Staabs and the Ilfelds (two families to whom author Miller is related) teaches young readers and listeners? It correctly paints the West as a place where amidst the majority white Christian culture, others could also flourish, among them Jews, Native Americans, African-Americans. Not only that, but social classes were so permiable that common folk could rub elbows with Presidents likes Hayes and Roosevelt, and socialize with Catholic prelates like Lamy.

In the Wild West, life could be difficult, and lawlessness and tragedy could strike, but for those who worked hard and understood that in America people’s prospects were limited only by their imaginations, places like New Mexico were the fabled melting pots of the American dream.

I recommend this book highly for children, as well as for the parents who might want to read it over their shoulders!

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. Your comment may be posted in the space provided below or sent to donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com