-65th in a Series-

Exit 54, Kitchen Creek Road, Cleveland National Forest, California

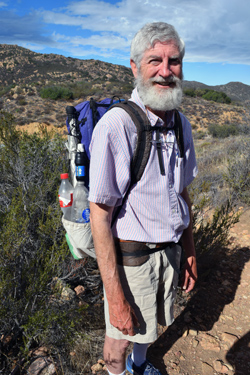

By Donald H. Harrison

CLEVELAND NATIONAL FOREST, California – The Pacific Crest Trail intersects with Kitchen Creek Road about 30 miles from where the trail begins on the U.S.-Mexican border and about 2,620 miles from where it ends on the U.S-Canada border.

CLEVELAND NATIONAL FOREST, California – The Pacific Crest Trail intersects with Kitchen Creek Road about 30 miles from where the trail begins on the U.S.-Mexican border and about 2,620 miles from where it ends on the U.S-Canada border.

Barney and Sandy Mann agreed to meet me there and answer some questions about the thrills and challenges of hiking a trail that is roughly equivalent to the driving distance between San Diego and New York via Interstate 40. Nothing about the Kitchen Creek Road crossing is extraordinary, except that it is easily reached by car. There is one part of the trail, up north, where one hikes some 200 miles without crossing a road.

The Manns are veterans of the Pacific Crest Trail, having hiked it in its entirety in 2007 on the occasion of their 30th wedding anniversary. As they tried to average between 20 and 25 miles per day on their hike, they reached Kitchen Creek on the second day of their five-month long backpacking adventure. They didn’t go that distance every day; on some days they rested and those were called “zero” days. Other days, they walked fewer than ten miles, and those were called “nearo” days. “Nearo,” it rhymes with “zero.”

Since their 2007 odyssey, the Manns have been active in the protection, preservation and promotion of the long, meandering pedestrian and equestrian trail that not only passes through the states of California, Oregon and Washington, but also traverses 25 national forests, 6 national parks, 5 California State Parks, 3 National Monuments in addition to other federal, state, local and private lands.

The Manns are members of Temple Solel in Encinitas. Barney, a retired real estate attorney, sings bass in the temple’s choir. Sandy, a PhD in molecular biology who taught advanced placement high school classes, has a brother who is a Presbyterian minister, while Barney, thanks to his sister, has a brother-in-law who is a rabbi. Sandy is a member with her husband of Reform congregation Solel’s chavurot. (friendship groups.) She became a Jew by choice while pregnant with the first of their three children.

Together the Manns are known as “trail angels,” who often pick up thru-hikers at San Diego’s airport at Lindbergh Field, provide them with food and overnight lodging at their home in the University City neighborhood of San Diego, and drive them the next morning to the U.S.-Mexico border at Campo to begin their treks. Barney recently served for three years as president of the Pacific Crest Trail Association (PCTA) and still serves on its board of directors. Additionally, he frequently writes about the trail’s history and customs in a variety of publications, including the quarterly of the Pacific Crest Trail Association, The Communicator. Remember the second word in the trail’s name, it is the Pacific Crest Trail—so named because it goes over mountain ridges. It is not the Pacific “Coast” Trail; in fact it is considerably inland from the beaches.

The Manns, like many thru-hikers, have “trail names” by which they introduce themselves and are known by other hikers whom they meet along the way. Their fellow hikers call Barney “Scout” and Sandy “Frodo.” There are stories behind each trail name, although Sandy’s is more esoteric. Barney was a Boy Scout who completed his first 50-mile hike when he was 13. He reached the “Life” rank, forever regretting that he did not continue on to “Eagle,” and later in life served for five years as a

scoutmaster. As much as he loves the Boy Scouts, Mann credits Temple Akiba in Culver City, where he grew up, for entrusting him with leadership positions. The temple operated a summer camp, and while a college student, Barney was its head counselor. The temple’s ruling board of directors trusted him to make decisions about the activities at the sleepover camp with little or no interference. Anyone familiar with temple or synagogue boards knows that is remarkable. Maybe someone should have given Barney the trail name “Akiba,” which no doubt would have identified him quickly to fellow Jews. Akiba was a martyr in the Bar Kochba revolt who was executed by the Romans. Executed? Maybe “Scout” is a better name after all! Barney likes to slip fitting Yiddish words like shlep and plotz into his trail conversations, so you don’t have to be an Einstein to figure out he’s Jewish. Moreover, Barney wears a Magen David on a chain around his neck.

Sandy’s brothers were Boy Scouts who also went on 50-mile hikes, but because she was a girl she didn’t get to go. She resolved early in life she would do it anyway, and became a backpacker. It was serendipitous that Sandy was a counselor for a public school’s outdoor school program that rented a San Gabriel Mountains camping facility at which Barney served as the director for three years between his college graduation and law school entry. Impressed by how well Sandy worked with youth, Barney hired her as a counselor for the upcoming summer camp session. Eventually, they fell in love and were married in 1977.

Before the Manns began their 2007 journey, Barney had a gold ring fashioned for Sandy on which were engraved the logo of the Pacific Crest Trail as well as depictions of some of the sights they were bound to see along the way. People who have seen or read J. R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy would instantly get the joke of Sandy’s trail name. Frodo was the inheritor of the One Ring who traveled to Mount Doom to destroy it. There, of course, the analogy breaks down. Notwithstanding her trail identity as “Frodo,” there’s no way that Sandy would destroy her keepsake ring – ever!

While Sandy good-naturedly accepted the Frodo name, she wished she would have been offered “Fleet Foot” or some other honorific. She explained that during a vacation from teaching duties, she read a lot of trail journals that thru-hikers had posted on line. Some of the people whom she read were of the opposite gender than what their names implied. “Girl Scout” and “Hot Sister” turned out to be guys, and “Cucumber Boy” was a girl. Annoyed, Sandy hoped for a trail name that wouldn’t cause gender confusion. But then came her ring, and “I said ‘no, Frodo is a guy’ but it didn’t work. … I was not thrilled but it made sense, so I accepted it.”

What were some of the more interesting trail names that they have encountered along the Pacific Crest Trail?

Barney told of a professional cellist, who was a first chair with his symphony, who one day was sitting around with other hikers and didn’t yet have a trail name. “He started a sentence with ‘wouldn’t it be awful if you got a trail name like’ – and here the creative side of his brain kicked in, but the other side was still resting –‘like Cuddles?’ And he is still ‘Cuddles’ today.

Sandy recalled the story of two male hikers who were resting at Warner Hot Springs, when the resort was open and welcoming to hikers. “There was a little 5-year-old girl birthday party going on and the girls were arguing: ‘I want to be Rainbow Sparkles,’ said one. ‘No, I want to be Rainbow Sparkles’ and one of the fellows turns to his buddy and says, ‘No, I am Rainbow Sparkles’ and he still is.

Warming to the subject, Barney told of a journalist who thru-hiked the trail in 2006. “One of the first places where you can go and get non-trail food is the Mount Laguna store, which is at PCT Mile 43, and the best he could do there was microwaved burritos.” In a scene reminiscent of the campfire scene in Blazing Saddles, the hiker felt the burrito gas roaring through him. A gal asked “what was that?” and he responded “that would be rolling thunder.” The man today remains “Rolling Thunder.”

For a thru-hiker, matters that are taken for granted in day-to-day life at home – drinking, eating, going to the bathroom, what clothing to wear, what supplies to keep near—all have to be thought about anew. In response to the trail, thru-hikers dramatically must change their life styles, so why not their names too? It’s not only the physical challenge and the ever changing scenery that attract the Manns and other thru-hikers; the opportunity to experience a kind of metamorphosis on the trail also beckons to them.

For Sandy, one call of the trail is “the community, the people. We have lots of friends that we still stay in touch with, who help us help hikers and whom we go to visit.” At the stage of life when their children are grown and they are hoping they soon will have grandchildren, the Manns delight in serving as mentors to young hikers. “We have some ‘trail children,’ a couple of trail daughters, a couple of trail sons,” Sandy said. “We get to hang out with young people. It’s a different kind of hanging out than in class; on the trail you are peers.”

“I am my best self when I am outdoors,” Barney says. Agreeing, Sandy says. “I tell people that it feeds my soul. It meets a need inside of me, just a real primal need. In science, we call it ‘biophilia,’ a love of nature.

Comments Barney: “There are so many things about it I love. I am around people who are feeling the same thing. If I love one thing in the world it is being kind. The default position on the trail is that in every interaction you are going to be looking out for each other. When I am out there at any time a small miracle can happen. They happen in our lives daily but we don’t see them because we are so busy, and out there we have the time. I might be at a pass, and an eagle might swoop by within touching distance and I can feel the displacement of air. That doesn’t happen in the city. I am walking in a place with no guard rails; there is something primal about that. I walk 25 miles a day and I can look back and see something in the far distance and the only thing that brought me from there to here was my feet. I look at objects in the distance, and my first thought is to approximate how long it will take to get there: two hours, half day, a full day. You get a sense of tremendous accomplishment. I feel special and important out there in a way that is entirely different than in the city. How often in your life do you get to do something that is extraordinary? By the mere fact of walking, twice now (the Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail), I have gotten to do something that is extraordinary.”

Sandy adds that on the trail “everyone is looking out for everyone else, everyone is eager to meet other hikers; they are wonderful people and that is a big part of it. A lot of it is you come to the top of a pass and there is new stuff ahead. It is amazing. I love seeing the trail snaking out ahead, and knowing that I am going to walk that and see what is around that bend. I am going to meet that challenge.”

While the trail can carry its lovers to the sublime, it also makes many a gritty demand upon them. Water, for example. The first 20 miles of the northbound trail has no water; hikers must carry their own, through a semi-desert climate. Water is heavy; the more you carry, the greater your load. The less you carry, the greater the risk of dehydration, maybe even sickness and death. Where is the balance? Barney carries on his back two 2-liter bladders, from which he can straw-sip while he is walking, and another two or three 1-liter plastic bottles in the side netting of his ultra-light backpack. “It is one thing to say 5-7 liters, but what that means is 10 to 15 pounds of water,” Barney cautions.

Besides for drinking, water is used for rehydrating lighter-to-carry dehydrated foods. Sandy says after she eats she will add water to her cup or tin, swirl it around, and then drink the remainder. Water must not be wasted! Most thru-hikers don’t carry soap; it requires water to lather and can be detrimental to the ecology. Instead they used alcohol-based cleansers like Purell to sanitize their hands.

Hiking 20-25 miles per day will burn 5,000-plus calories, and trail food will replenish about 1,500 to 2,000 calories of that, according to Barney. One result is that thru-hikers can burn off a lot of body fat. Another is that in those places where the Pacific Crest Trail passes near a restaurant, hikers tend to eat ravenously.

Bears eliminate their body waste in the woods and so do thru-hikers. Following the maxim of “leave no trace,” the hikers pack out their used toilet paper, carrying it in a Zip-Loc bag until they can safely dispose of it in a trash can. This may not sound pleasant, but even more unpleasant would be to find the trail strewn with used toilet paper. Some 1,800 thru-hikers registered for the Pacific Crest Trail in 2015; imagine how disgusting it would be if they all just left the paper where they pooped. Even burying it doesn’t solve the problem; animals will dig it up. So packing it out is the solution.

In their role as trail angels, Barney and Sandy sometimes pick up at the airport hikers who they can tell are not properly prepared for the journey. Sometimes they come wearing jeans and cotton shirts, neither of which will dry easily after a rain. Polyester clothing is recommended. There was one hiker who didn’t bring a sleeping bag; she figured she’d just sleep on the ground. Sandy told her she wouldn’t drive her to the starting point unless she borrowed a sleeping bag from the Manns. It can get freezing cold in the mountains, especially toward the northern end of the trail. Whenever they see a would-be hiker who is ill-prepared, the Manns quietly pass the word to other hikers: “Keep an eye on so-and-so; don’t let him get into trouble.” The beauty of the hiking community is that they will take the admonition to heart.

Although they had joined the Pacific Crest Trail Association before their 2007 hike, it was during their odyssey that Barney decided that he would become more active in the association. He became the association’s fundraising chair, and in 2008, he was invited to join the board. Eventually, he became the board chairman, carefully developing in association with the PCTA’s executive director a comprehensive strategic plan.

About 90 percent of the trail is in public land, with the other 10 percent in easements across private land. To protect the trail for posterity, Barney and the Association would like to eventually have as much of that private land as possible to be acquired by the public. Financed with public funds and private donations, the trail needs continuous maintenance, additional signage, and the benefit of educational outreach. With fewer than a score of paid staff, but with some 1,500 volunteers and 10,000 members, many of them drawn to the Pacific Crest Trail as the result of Reese Witherspoon’s portrayal of Cheryl Strayed in the 2014 film Wild, the PCTA is made up of people who like nothing better than to overcome challenges.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com