Story by Donald H. Harrison; Photos by Shor M. Masori

SAN DIEGO – Trina Robbins is known in the comic book industry as the first female artist to draw Wonder Woman, back in 1986 for D.C. Comics. She went on to become a mentor for other women comic book artists, and that was apparent on Thursday, July 20, at the ComicCon convention when a panel on a recent book that she had compiled featured four women artists and one “token male” as illustrators.

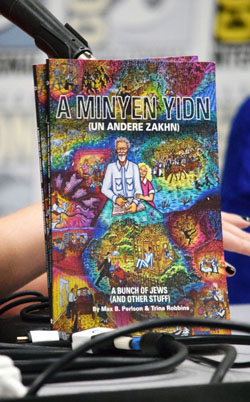

The book under discussion was A Minyen Yidden, which Robbins candidly described as her “atonement” for ignoring her father’s Yiddish language stories, published in 1938, the year of her birth. Her father, Max B. Perlson, was a writer for such Yiddish language newspapers in New York as Der Tag (The Day) and Forvitz (The Forward). When she was a child, Robbins was embarrassed by Yiddish, explaining on Thrusday: “As a kid I wanted to fit in. We were the only Jews in a Catholic neighborhood and I felt that all the Christian kids were Americans, and we weren’t because we were Jewish. I felt like we didn’t belong. I didn’t want anything to do with my father’s Yiddish.”

The book under discussion was A Minyen Yidden, which Robbins candidly described as her “atonement” for ignoring her father’s Yiddish language stories, published in 1938, the year of her birth. Her father, Max B. Perlson, was a writer for such Yiddish language newspapers in New York as Der Tag (The Day) and Forvitz (The Forward). When she was a child, Robbins was embarrassed by Yiddish, explaining on Thrusday: “As a kid I wanted to fit in. We were the only Jews in a Catholic neighborhood and I felt that all the Christian kids were Americans, and we weren’t because we were Jewish. I felt like we didn’t belong. I didn’t want anything to do with my father’s Yiddish.”

However, nearly 80 years have elapsed and as Robbins grew older, she grew wiser. When her daughter found a copy in Yiddish of A Minyen Yidden, Robbins, now an accomplished story teller, read it in translation and was delighted with the verbal sketches her father had composed about life in the shtetl of Duboy, in modern-day Belarus, and in Brooklyn, where he had immigrated. She decided “it would make a good graphic novel.”

She went through the stories that she liked best and parceled them out to various artists, including those who were with her on a panel moderated by Hope Nicholson, the Winnipeg, Canada, publisher of Bedside Press. The artists, both Jews and non-Jews, included Barbara “Willy” Mendes, Elizabeth Watasin, Steve Leialoha, Miriam Libicki, and Jen Vaughn.

Mendes, who has a nearly half-century long working relationship with Robbins, grew up in a secular home despite being the great granddaughter of a Sephardic rabbi who served New York City’s Shearith Israel congregation. However, in more recent years, she has become an Orthodox Jew as well as a painter, muralist, and owner of the Barbara Mendes Art Gallery on Robertson Boulevard in Los Angeles. Mendes drew the cover of A Minyen Yidn (which the panelists translated as “a bunch of Jews), which depicts a smiling Perlson and an adoring Trina in the center of a tableau of scenes illustrating some of the short stories in the book. As a real child, Trina may not have been so admiring of her father, but on the cover of this anthology, which one hopes will have some permanence, she dotes on him.

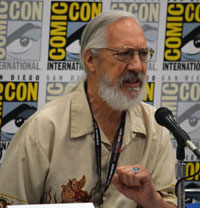

The opening story, “Bizness,” was drawn by Leialoha, who has drawn comics ranging from Star Wars to Howard the Duck. He described himself as coming from a multi-ethnic family. His father is Hawaiian, and his mother a Sephardic Jew, so perhaps, he quipped, he and Willy are related. In “Bizness,” the character Perlson sets the scene for the rest of the book. He is in Brooklyn telling children about his life in Duboy. For Leialoha, this was an opportunity to draw in two styles – the Brooklyn parts of the story in his own modern style; the Duboy portion of the story, an homage to cartoon great Will Eisner, who would have been 100 years old this year. The gist of the story is that in Duboy, everyone was so busy with the “bizness” of praying, they didn’t have time for anything else. That’s probably why they were all so poor.

Watasin, a quiet-spoken Buddhist whose own book Medusa: A Dark Victorian Penny Dread was the winner of the 2015 Rainbow Award for Best Lesbian Fantasy, illustrated “Reb Smuel-Khayim,” the story of a man who was quite poor, but who acted as if he deserved all the honors due the rich and powerful, and more. A short episode pictures him as the rich man he imagines himself to be, on a train, counting out money to an oxen trader. The problem was that he counted the money into his own hand, instead of into the trader’s.

The two other panelists, Jen Vaughn and Miriam Libicki, illustrated Perlman stories that were set in America.

Vaughn drew “Faydo,” a story of a German Shepherd raised from puppyhood by a family whose mother had a heart ailment and whose daughter had incurable cancer. When they both passed, Faydo really had no one left to live for. So he closed his eyes and died too.

Vaughn’s own works include such titles as Adventure Time: 2013 Spooktacular and Avery Fatbottom: Renaissance Fair Detective.

Libicki, who grew up an Orthodox Jew but whose life, including a stint serving in the Israeli Army, has become more secular, illustrated what she described as one of the most non-Jewish stories in the book, “How Mr. Remson Lost His Pension.” There was no mention of Remson’s religion in the story, but for the record, Robbins believes the man her father wrote about was in fact Jewish. Remson had worked all his life for the railroad, and was an exemplary employee. However, his friends got him to celebrating his retirement, with many an alcoholic drink, with a day too early.

Publisher Nicholson, in leading the panelists through a discussion of the book, laid particular emphasis on the amount of research that goes into a graphic novel in order to draw the wardrobes, buildings, furnishings, and transportation modes correctly. Whether it was photos of German Shepherds for Vaughn, New York City buildings for Leialoha, railroad cars for Libicki, or shtetl life for Watasin, appropriate models were needed to provide the stories the necessary verisimilitude.

There were some interesting sub-themes throughout the panel discussion, and following questions and answers, such as how to draw a Jewish woman. In Duboy, most of them wore sheidels and scarves over their heads, or as Robbins put it: “None of them were babes.”

A questioner from the audience asked the panel what they thought of Gal Gadot’s current movie portrayal of Wonder Woman.

Robbins said the minute that she saw Gadot, who is Israeli, “I thought this is the real Wonder Woman, who is Greek, Mediterranean. Gal Gadot is Mediterranean; this is what Wonder Woman really looks like. So now we know!”

Mendes, however, had a much different take: “Someday the world will discover a truly womanly definition of courage, a feminine definition of heroism, and it is not punching people,” she said. “We are at the tiny beginning of learning about women, learning what is important to us, learning about what is holy about us, learning what we have to say, learning what we like. We are at the early, early dawning knowledge of women.”

Nicholson, who besides publishing comic books is a historian of the genre, commented that the character of Wonder Woman has changes so much. “She wasn’t always a warrior princess,” she noted. “She was a character devoted to peace keeping, devoted to sisterhood, feminism. That is something that seems to have changed.”

*

Harrison is editor and Masori is a staff photographer for San Diego Jewish World. They may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com and shor.masori@sdjewishworld.com