Story by Donald H. Harrison; photos by Shor M. Masori

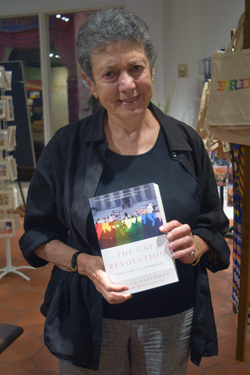

SAN DIEGO – Lillian Faderman, an historian of gay and lesbian progress and struggles in America, is the curator of the San Diego History Center’s newest exhibit “LGBTQ+ San Diego: Stories of Struggles and Triumph,” which will last a year, or more if attendance merits. The biographer of slain San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk, who was the first openly gay candidate elected to high office in California, Faderman says San Diego’s LGBTQ+ community took to heart Milk’s advice to “come out” and has since proved Milk’s wisdom.

Although Milk was a San Franciscan, he knew San Diego very well, having served here as a Navy lieutenant, and making visits thereafter. “Coming out” was one of Milk’s themes in the 1970s, according to Faderman. He taught, “you have to come out, you have to come out to everyone, even to the wait staff in the restaurant where you go and to the people who are the cashiers in the supermarkets where you shop. It is important that people know who we are.”

Faderman said that in the 1990s, “an interesting Gallup Poll was taken across the United States, and San Diego as well, and only 22 percent of Americans said they had a close friend or relative who was lesbian or gay. In 2010, a Gallup Poll was taken asking the same question and three times as many people said they had a close friend or relative who was lesbian or gay. The difference was not that lesbian or gay people had grown in numbers but that we had come out – that made a huge difference.”

“I’ve seen it with the groups I speak to,” Faderman added. “If your son or daughter, or your aunt or your uncle, or your neighbor or coworker tells you that they are gay—or now, ‘LGBT’—you can’t think of those people as lurking in the shadows, ready to pounce on some 14-year-old kid, because you know that it is your son or daughter, or your best friend, or somebody you admire at work. Coming out had made a huge difference.”

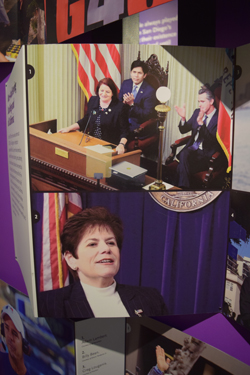

In the political realm in 1993, that advice paid off when Christine Kehoe, who acknowledged being a lesbian, was elected to the San Diego City Council in District 3, and subsequently was elected to the state Assembly and the state Senate. That City Council position, which represented the heavily gay Hillcrest neighborhood and surrounding areas, meanwhile, has been occupied continuously by gay and lesbian office holders, among them Toni Atkins, Todd Gloria, and Chris Ward. Atkins went on to be elected to the state Assembly, then as Assembly Speaker, and thereafter was elected to the state Senate. Today, Atkins is the State Senate president pro tempore – “a remarkable achievement,” Faderman says. Gloria went on to succeed her in the state Assembly, where he currently serves.

Whereas the Hillcrest area was the seat of gay and lesbian success, other districts also elected gays and lesbians to office. Carl DeMaio, today a radio commentator and leader of the statewide effort to roll back gasoline taxes, was elected in District 5, which includes Rancho Bernardo, Mira Mesa, and other suburban communities along the Interstate 15. Currently Georgette Gomez, who calls herself a “queer,” which Faderman said is a more fluid term than “lesbian” or “bisexual,” was elected from District 9, which includes the area around San Diego State University and neighborhoods to the west along such thoroughfares as Adams Avenue, El Cajon Boulevard, and University Avenue.

The popularity of gay and lesbian candidates has also been seen in contests for other offices. Faderman noted that a fellow Jew, Bonnie Dumanis, was first elected as a municipal court judge, later as the nation’s first lesbian district attorney, and today she is running for the position of county supervisor. Kevin Beiser was elected from such suburbs as San Carlos, Del Cerro, and Allied Gardens to serve on the San Diego County School Board, on which today he serves as the president.

Overall, suggested Faderman, San Diego probably has elected more gays and lesbians to public office than even San Francisco has.

Faderman, 78, had resided part-time in San Diego since 1994 with her partner of 46 years, Phyllis Irwin, and made her residence here permanently a couple of years ago.

She commented that it was not so long ago in California generally and San Diego specifically that both law enforcement and the school establishment were outright hostile to gays and lesbians.

The scholar and curator said that she came “out” as a lesbian since the 1950s, but that was only to her friends and relatives and not to the world at large. “I came out closeted,” she said. “I went to graduate school and got my PhD, and of course I was closeted. If I had come out publicly in the ‘50s I couldn’t have gone to a university because there were witch hunts in universities. There was no way I could have survived as a social being coming out in the 1950s and the 1960s.” But in the 1970s, times and attitudes began to change and that is when she came out in a public way.

She recalled, “I started UCLA as a freshman and then I transferred to Berkeley and I did most of my undergraduate work there. I remember very well that at UCLA we were given a battery of tests, psychological tests, and I remember one question kept repeating itself, like ‘Have you ever kissed a person of the same sex?’ and then 10 questions later, ‘Are you attracted to people of the same sex?’ I knew to say ‘no;’ I’m sure all gays and lesbians knew to say ‘no.’ I couldn’t figure out why that question would be on that test, and then I wrote a book in 1991 called Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers,” I did a lot of research for that. I came across an article that had been published in 1954, four years before I started UCLA. It was written by the man who was the dean of students, and another guy who was the associate dean of students, coauthored by them. Their point was that it was the job of the dean of students to ferret out the homosexuals and either assure that they got psychiatric treatment to cure them or expel them from the university lest they spread homosexuality in the university. It was published in a magazine called School and Society that was for administrators of schools. I knew I had to be in hiding in the 1950s, and even when I took a job as a professor in 1968 at Cal State University Fresno, I knew that I could never make any pronouncements. By the 1970s, things had changed significantly. There was Stonewall (a well-publicized gay uprising against a police raid in 1969 against the Stonewall gay bar in Greenwich Village, New York City); the feminist movement, and everything that followed. I started doing lesbian research in 1975.”

As in New York City, police in San Diego—abetted by the news media—engaged in homophobic persecution. “For instance,” she said, pointing to one of the exhibits at the San Diego History Center, “this newspaper article appeared in 1974 about gay men who were arrested at the May Company. It was public shaming. Their names appeared, along with their ages, addresses, and occupations to shame them as much as possible.”

Law enforcement had no mercy on those of their profession who secretly were gay. Faderman pointed to a letter written by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to his second in command Clyde Tolson “saying he met this wonderful young man, just the kind the FBI should hire,” named Frank Buttino. “They hired him, promoted him, he was the head of the San Diego office, and then someone outed him 20 years later. He was fired, and he fought, and he won, so the FBI can no longer discriminate against people because they are gay.”

The exhibition traces some of the outrages committed against the gay and lesbian community, as well as various successes the community had in winning acceptance from the general community.

There is a memorial plaque in Hillcrest, reproduced at the San Diego History Center, for John Robert Wear, 17, who was beaten to death while three of his friends were injured by thugs who had jumped out of their car, called the friends who were walking down the street “faggots” and pounced upon them. Ironically, said Faderman, the young men were not gays.

The exhibition deals with the issue of gay marriages, with one picture showing a lesbian couple at Temple Emanu-El signing a ketuba under the proud supervision of Rabbi Martin S. Lawson. In another area of the exhibition which displays testimonies videotaped by attendees, Rabbi Laurie Coskey told of her time at Congregation Beth Israel when she was one of the earliest rabbis willing to perform for gay and lesbian couples, marriage or “commitment” ceremonies, depending on what was legal at the time. Faderman said that she and her partner Phyllis Irwin have visited a number of synagogues in San Diego, and have been impressed by how welcoming they are to gay and lesbian couples. She particularly mentioned Rabbi Scott Meltzer at Ohr Shalom Synagogue and Rabbi Devorah Marcus, who succeeded Rabbi Lawson as spiritual leader of Temple Emanu-El. Now, said Faderman, she is considering having an adult bat mitzvah, either before or in celebration of her 80th birthday, and Irwin is now considering converting to Judaism.

While together four years shy of a half century, Faderman and Irwin have had a series of legal relationships as laws regarding same-sex couples have changed.

“My partner and I had more legal relationships than anyone in the whole world,” Faderman declared. “We have been together for 46 years. We have a child together. I had a child through donor insemination. He is 43 years old now, Avrom, named after my grandfather who I never met because he died in the old country … Avrom and his wife have a son today, our grandson. … In the early 1980s when our son was six or seven, I was traveling a lot because I had just published a book. I worried that if he got sick, my partner could not take him to the doctor without a note from me. If anything happened to me on my travels, she would have no legal claim to him.

“In those days in the State of California,” she continued, “you could adopt if there was more than a 10-year-difference, and she is 11-years older than I am, so we did an adult adoption. So, we did that until ‘domestic partnerships’ became legal in California. So, we had a domestic partnership, and then it became even more legal: we got all the rights except the right to say, ‘We are married,” so we did that, and then in 2008, there was a very brief period, six months in fact, when same sex couples could get married. We did it in San Diego because we spent the summers here, and it was already June. We got married in 2008 by someone at the county clerk’s office, a woman. That was the first time we got married, and we were permitted to stay married – 18,000 couples in California married, and they could stay married, but that November – the same November that President Obama was wonderfully elected –there was Proposition 8 on the California ballot,” which voters approved, ending same sex marriages temporarily, until 2015, when the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriages are legal.

“In 2015,” Faderman recounted, “The New York Times was doing an article on same-sex couples who first had an adoption as Phyllis and I did, and then got married, and so the reporter asked in an interview, ‘And when did you undo the adoption?’ and I said we never did. We had actually gone to a lawyer here (in San Diego) in 2008, and I think she probably did her research on the Internet 10 minutes before we came in. She probably Googled “same-sex marriages-adoption” and got Michigan where you don’t have to undo the adoption. I said, ‘We never did,’ and he said, “I think you are wrong about that; I think you have to undo it.’ I didn’t pay much attention but when my book, The Gay Revolution, came out, I was invited to speak at the Los Angeles Public Library. After I spoke a lesbian lawyer came up to me and said all the lawyers are talking about that New York Times article: ‘I think you guys have to undo the adoption and get married again.’ And so we undid the adoption by signing some documents and in 2015 we got married again. Phyllis unadopted me. Meanwhile, our son always had called her Mama Phyllis. He is 43 now and has a son who is 12, and he said to her, ‘But you always have been my mother, and now I have no connection to you legally. Can you adopt me? And she did. She did an adult adoption of him. So, we have a lot of legal ties. My point is we had to do so much to have legal ties.”

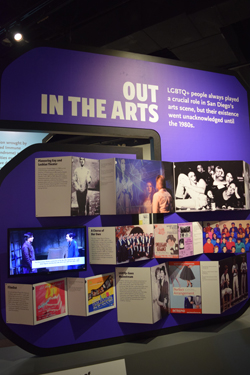

The “LGBTQ+ San Diego: Stories of Struggles and Triumph” exhibition is constructed very similarly to the recently-ended exhibition curated by Joellyn Zollman on the history and contributions of San Diego’s Jewish community, in which Zollman illustrated the thesis that Jews have been both insiders and outsiders since they first arrived in San Diego in 1850. Faderman said that she consulted with Zollman on several occasions as she was designing the LGBTQ+ exhibition. Like the Jewish exhibition, the LGBTQ exhibition utilizes eight 10 by 10 “pillars” in the shape of the letters S-A-N D-I-E-G-O on which to mount photographs, video monitors, newspaper clippings, and other documents. Additionally, both exhibitions had a time line covering much of a single wall, a video station for attendees to record their own experiences, and a family room where people could rest, read, and look at an assemblage of mounted photographs. The Jewish exhibition drew on the collection of the Jewish Historical Society of San Diego, while the LGBTQ+ exhibition drew on the collection of the Lambda Archives.

Although similar in presentation, the stories are different; discrimination against Jews was far more subtle than that against gays and lesbians. The LGBTQ community had to contend against hostile legislation, such as the unsuccessful 1978 Initiative sponsored by State Senator John Briggs that would have banned gays and lesbians from working in the public schools. The military also did what it could to discourage, even criminalize, homosexuality. For example, there was a retired admiral, Selden Hooper, living in Coronado, whom the Navy suspected of having relationships with men who still were in the Navy. “They commandeered the house next door to spy on him and they discovered that there were men going into the house, sitting at the table, and at one point they could see two men dancing,” Faderman related. “So, they forced him back into the Navy so they could court martial him, and take away is rank and pension.” Hooper had commanded the destroyer USS Uhlmann during World War II.

The first Gay Pride march was organized in 1975 in San Diego, and because police would not issue a parade permit, about 200 proud marchers kept to the sidewalk, stopping at traffic signals. But the following year, the Gay Pride parade did receive a permit, and the parade grew each year, to 100,000 participants and observers in 1997 and to 200, 000 in 2016. This year’s Pride parade will begin at 11 a.m., Saturday, July 14, and follow a 1.5 mile route from University Avenue and Normal Street. The parade is one of several Pride events scheduled for this weekend.

Some of the exhibits deal with the AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) crisis, in which numerous homosexual men were stricken fatally with what up to then had been an unknown disease. Some of the vitriol directed at the gay community was depicted by a picture of homophobic protesters wearing Hazmat suits to spread the lie that it was dangerous to even be around gay men. In fact, AIDS was triggered by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) spread by the exchange of bodily fluids. A counter exhibit discussed the creation of a group known as Blood Sisters, a lesbian group that donated blood for men who were victims of AIDS “because the gay community could not give blood, but lesbians (who had the lowest incidence of exchanging bodily fluids with men) could,” according to Faderman.

As the gay and lesbian community matured, it developed a myriad of organizations that not only dealt with internal issues but which also reached out to the larger community. Additionally, there were cultural organizations like the Gay Men’s Chorus and the San Diego Women’s Chorus, and the Diversionary Theatre; political organizations like the San Diego Democratic Club and the San Diego County Log Cabin Club, and chambers of commerce like the Greater San Diego Business Association. A number of these organizations pointedly refrained from identifying themselves as “gay” or “lesbian,” according to Faderman; “they were more conservative.” She said although it was organizations such as these that flourished, earlier protests by radical groups such as the Gay Liberation Front helped spur the community to organize.

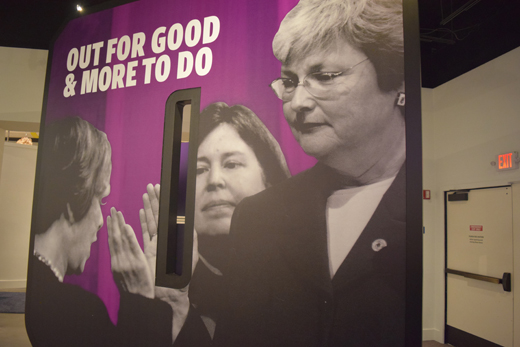

One group that offered a double entendre in its name was “Gay for Good,” whose members proclaimed their everlasting gayness and who also contributed funds and volunteer time for charitable projects in the general community.

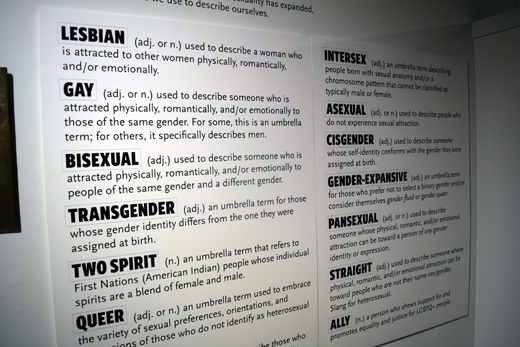

The exhibition features a chart helping people unfamiliar with the lexicon of the LGBTQ+ world to understand who is who.

Faderman said some of the labels have interesting histories. While “lesbian” derives from the Isle of Lesbos, where the ancient Greek poet Sappho wrote of love and attraction between women, the history of the word “gay” to describe homosexual men is murkier. “In the course of my research, I found a cartoon from about the 1880s or early 1890s of two prostitutes standing in front of a street lamp, looking exhausted, and calling themselves ‘gay,’ and the irony of it is very clear,” Faderman said.

“My theory is that the term first came into the heterosexual prostitute community, and then gay hustlers in the late 19th century took the term to describe themselves, and then the term was used to describe homosexual men, not necessarily hustlers, but all homosexual men in the early 20th century. By 1912, it was used to describe lesbians as well, and I know that because there is a book by Gertrude Stein called A Long Gay Book, which talks about both men and women. Stein wrote an essay at that time called “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene” which was about two lesbian friends of hers and she keeps repeating in her inimitable style, “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene were gay; they were gay every day; every day they were gayer and gayer.” The essay, or short story, was published not until 1922 in Vanity Fair and I’m sure most people had no idea except for lesbians and gay men who had an idea what that meant.”

The historian said that when she came out in the 1950s, the term “gay” meant to be “out there, to be loose.” At that time, she said, straight people generally didn’t know the meaning of the word ‘gay.’ “In fact, a way that you could figure out if someone was gay or not was that you could say in a cheery voice, ‘Are you gay?’ and if the person said, ‘I am a little depressed today,’ you knew he wasn’t.”

The chart explains such terms as “bisexual,” “transgender,” “two spirit,” “queer,” “intersex,” “asexual,” “cisgender,” “gender expansive,” “pansexual,” “straight” and “ally,” affording a view into the diversity of sexuality within the community. Faderman said various terms came into vogue as different groups sought to assert their identity. Lesbians, for example, wanted to differentiate themselves from “gays,” who were men.

The debate sometimes heard about whether homosexuality is a matter of “nature” or ‘nurture,” in Faderman’s view is an oversimplification, regardless of how one answers. She said, “it is a matter of who you meet at a particular time. Maybe nature has something to do with it. I think it is very complex; I’m just troubled by attempts to make a sweeping generalization. Some people say ‘I was born that way;’ maybe they were, but not everyone would say that. Some people might say, ‘I was born with the tendency, and my experiences confirmed my sexuality,’ but it is the same for heterosexuals. I think sexuality is very complex. It bothers me when it is reduced to nature or nurture.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com