Story by Donald H. Harrison; Photos by Shor M. Masori

STANFORD, California – The signature landmark on the Stanford University campus is the Hoover Tower, named for one of the students in its very first class, Herbert Hoover, who in 1929 would become the 31st President of the United States.

Whereas today, admission to Stanford is accorded only to the very upper elite strata of high school students, Hoover, himself, had never attended high school, and failed all his entrance exams, save mathematics. However, the mathematics professor who administered the test, Dr. Joseph Swain, saw potential in the 16-year-old, mostly self-educated, fellow Quaker, and arranged for Hoover to go to the Stanford campus, which still was being built, ahead of the other pioneer students who entered in 1891 and would graduate in 1895. Over the summer prior to the start of his first semester, Hoover was tutored in a variety of subjects, and although he never was considered a top student, he distinguished himself in many other ways.

Because he was there ahead of the other students, “Bert” Hoover was the first student to sleep under the roof of Encina Hall, a dormitory. It’s fairly well known on campus that he lived in Room 38. By his second year, however, he moved off-campus to less expensive housing more in line with his meager budget.

Herbert Hoover: A Public Life by David Burner and Herbert Hoover: A Biography by Eugene Lyons tell how Hoover supported himself by organizing a newspaper delivery service, and later a laundry service, in which he arranged for dirty clothes to be picked up from students every Monday morning and returned clean to them the following Saturday afternoon. Among the snobbish sorority and fraternity members of his day, impoverished entrepreneurs like Hoover were considered socially inferior. Eventually, Hoover became one of the leaders of the “Barbarians,” who challenged the Greek letter organizations for control of Stanford’s student government. Successful in the revolt against elitism, Hoover was elected treasurer of the student body, a position akin to serving as general manager of all the school’s extra-curricular enterprises.

The students, under Hoover’s tutelage, were responsible for funding construction of the grandstand, baseball field, and track. At one point, Hoover played shortstop for the Stanford team, but an injury forced him to retire to behind the scenes of athletics. It was Hoover who arranged the first football game between Stanford and Cal Berkeley, which Stanford won. Not all his enterprises were so successful. A lecture he arranged for Populist orator and presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, failed to attract a crowd, and a similar fate awaited a concert arranged by Hoover for pianist Ignace Paderewski. Needing to make certain that the student body had sufficient revenue, Hoover arranged for associates to stand along all sides of the ball field, lest anyone gate crash. On two occasions, he challenged very distinguished men to present their tickets after other students were too embarrassed to make such a demand. In both cases, Hoover collected the ticket prices, respectively from former U.S. President Benjamin Harrison and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Hoover years later was to reminisce: “Justice must occasionally be done even to ex-Presidents.”

Academically, Hoover was mentored as a geology student by Professor John Branner, who became a lifelong friend. During one summer vacation, Branner arranged for Hoover to map outcroppings on the northern side of the Ozarks for the Geological Survey of Arkansas, and the following summer to serve as an assistant in the High Sierras to Dr. Waldemar Lindgren, who also became a good friend.

During the school term, Hoover served as an assistant to Branner, and reportedly was so smitten he could do nothing but stammer when introduced to a new student in the department, Lou Henry, daughter of a Monterey banker and an excellent equestrian. Notwithstanding the fact that she immediately had been snapped up by a fashionable sorority, and thus was subject to the snobbish attitudes of her sorority sisters, she found the shy, but well-organized and politically astute Hoover exactly to her liking. They waited three years for her to graduate from Stanford, and then a year after that, to be married in Monterey. Like her future husband, the future First Lady had served as president of Stanford’s Geology Club.

After his graduation in 1895, Hoover initially was hard-pressed to support himself. He applied in San Francisco to the offices of Louis Janin, a mining engineer affiliated with the Rothschild interests in America. Janin told him there was a long line of aspiring geologists ahead of him, and that in any event there were no positions available, except one as a clerk typist. Hoover astutely accepted the position on the spot, intuitively understanding that if he could be near Janin in the office, he could learn from him. For his part, Janin soon recognized Hoover’s aptitude and training, and assigned him to the Sierra Mountains as a mine scout.

It was a brief association with Janin, because Hoover soon was recruited by the British firm of Bewick, Moreing, to evaluate and administer mines in Western Australia, and later China. Eventually he traveled to various locales all over the world in behalf of the British firm, developing such a solid reputation for rejuvenating mining operations that he was able to open his own London-based independent consulting company. Having become a wealthy man, Hoover returned on occasion to Stanford to deliver lectures, and also to present the university library with books and papers that he had gathered during his travels.

Biographer David Burner wrote that “No other President except Woodrow Wilson so closely identified himself with his alma mater in later life. During his business career, Hoover brought for the library many hundreds of books, especially on Australia and the Far East. In a letter of 1908 to Theodore H. Adams, who then taught history at Stanford, he announced he would give complete sets of several publications of scientific societies ‘in relation to Asiatic matters, particularly early Jesuit publications’ and he wrote Adams in 1912 that he was sending some shelves of books on China.”

Hoover became a trustee of his alma mater in 1912, later donating $100,000 for a Student Union, and helping to found after World War I both the School of Business and the Food Research Institute.

Wrote Burner: “His most impressive achievement was to salvage quantities of fugitive literature from Europe in the same era and house it on campus at the Hoover War Library, later renamed the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace.”

Hoover’s association with the Rothschild family enterprises was tangential, but somewhere along his life’s journey, he developed a sympathy for other Jews. As head of the American Relief Administration, in the immediate aftermath of World War I, Hoover was instrumental in having Henry Morgenthau appointed as a commissioner to investigate the slaughter of 280 Jews in Poland in April 1919. As U.S. President in 1932, he appointed Benjamin Cardozo to the U.S. Supreme Court, the second Jew so named. Justice Louis Brandeis, with whom Cardozo served, was the first Jew to become a Supreme Court Justice; appointed by Woodrow Wilson.

*

The 285-foot Hoover Tower was completed on Stanford University’s 50th anniversary in 1941. Inside it and around it are various reminders of Hoover’s career, including engineering memorabilia, his bust, and a seal of the President of the United States. A sign informs visitors that “the carillon of thirty-five bells in this tower was originally cast by Marcel Michiels in Tournai, Belgium for the New York World’s Fair 1939 and 1940. The carillon is a gift to Stanford University from the Belgian American Educational Foundation with which are associated the Belgian universities and educational foundations recipients of endowment funds from the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1919. Dedicated on June 20, 1941.” Subsequently 13 more bells were added to the carillon, and the largest bell in the assemblage was inscribed Uno Pro Pace Sono, Latin for “For Peace Alone Do I Ring.”

The 285-foot Hoover Tower was completed on Stanford University’s 50th anniversary in 1941. Inside it and around it are various reminders of Hoover’s career, including engineering memorabilia, his bust, and a seal of the President of the United States. A sign informs visitors that “the carillon of thirty-five bells in this tower was originally cast by Marcel Michiels in Tournai, Belgium for the New York World’s Fair 1939 and 1940. The carillon is a gift to Stanford University from the Belgian American Educational Foundation with which are associated the Belgian universities and educational foundations recipients of endowment funds from the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1919. Dedicated on June 20, 1941.” Subsequently 13 more bells were added to the carillon, and the largest bell in the assemblage was inscribed Uno Pro Pace Sono, Latin for “For Peace Alone Do I Ring.”

In the early years of World War I, while the United States still was neutral, the decimation of the Belgian countryside by German troops, and the embargo on shipping to German-occupied Belgium imposed by Great Britain and its Allies, created a Belgian hunger crisis. Hoover from his consulting offices in London, with the permission of President Woodrow Wilson, organized the Commission for Relief in Belgium, which arranged shipments of millions of pounds of food to that country. The Germans permitted this activity because the U.S. at the time was a neutral party, and the British also acceded. Once the United States entered the Great War in 1917, President Wilson appointed Hoover to head the U.S. Food Administration, to assure the nutritional needs of this country and those of the Allies. When the war ended, numerous European countries were destitute, prompting creation of the American Relief Administration, with Hoover at its director general.

It was in 1919 during the Paris Peace Conference—one full century ago—that Hoover sent a message to Stanford offering $50,000 for the university to build a collection of materials documenting the war. According to the Hoover Institution’s 2018 annual report, he was “planting the seeds of a remarkable enterprise that stands today as the nation’s center for public policy and archival research: the Hoover Institution.” True to this purpose, a current exhibit at the Hoover Institution is a collection of photographs taken by American journalists during the Vietnam War, showing not only warfare but also outreach efforts to Vietnamese civilians by American soldiers.

“This institution supports the Constitution of the United States, its Bill of Rights and its method of representative government,” Hoover would declare many years later, in a statement that has become the Hoover Institution’s credo. “Both our social and economic systems are based on private enterprise from which springs initiative and ingenuity … Ours is a system where the Federal Government should undertake no governmental, social or economic action, except when local government, or the people, cannot undertake it for themselves. … The overall mission of this institution is, from its records, to recall the voice of experience against the making of war, and by the study of these records and their publication, to recall man’s endeavors to make and preserve peace, and to sustain for America the safeguards of the American way of life. This institution is not, and must not be, a mere library. But with these purposes as its goal, the Institution itself must constantly and dynamically point the road to peace, to personal freedom, and to the safeguards of the American system.”

Following World War I, so popular did Hoover become that he was encouraged to launch a Republican bid for the U.S. Presidency in 1920, but ultimately withdrew and endorsed Warren Harding, who appointed Hoover as Secretary of Commerce. In 1920, Hoover had a house built on the Stanford campus for himself and his family – a house which subsequently became the residence for Stanford’s presidents.

Hoover served as Commerce Secretary and in numerous ad hoc positions through the presidencies of Harding and Calvin Coolidge. When the latter declined to run for reelection in 1928, Hoover was able to gain the necessary support for his own bid. He formally accepted his nomination in 1928 in a ceremony conducted at the Stanford Stadium.

Anyone who has seen the musical Annie knows that President Hoover was blamed—perhaps unfairly—for the Great Depression. As stocks plummeted and banks failed, people were thrown out of work, with many losing their homes. Ersatz townships with temporary shelters were derisively described as “Hoover-villes,” while cries for the federal government to employ massive amounts of people were rejected by Hoover, following the precepts outlined above. In the 1932 election, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who promised various public works programs to get America working again, defeated Hoover, and was subsequently reelected three times. After Roosevelt took office, the Hoovers returned to their home on the Stanford campus. Hoover remained there until after the death in 1944 of his wife, whereafter he relocated to New York City, residing there until his own death in 1964.

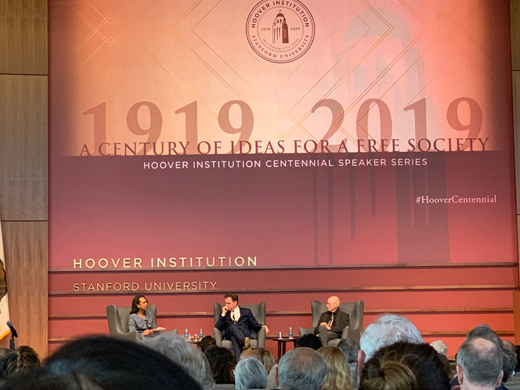

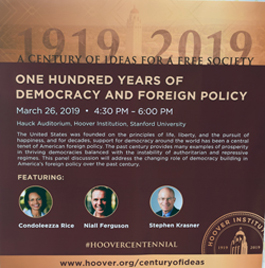

The Hoover Institution over the years gathered a group of Fellows, who proposed, analyzed, and critiqued public policy generally from a similar Republican perspective as Hoover. This year being the 100th anniversary of the Institution’s founding, an 11-part speaker series, titled “A Century of Ideas for a Free Society,” has been arranged, with the first occurring on March 26th. It featured former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who had served in George W. Bush’s administration, and who currently serves as the Denning Professor in Global Business and the Economy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, as well as a professor of political science at Stanford University. She conducted a trialogue with Niall Ferguson and Stephen Krasner, who both are senior fellows of the Hoover Institution. In the audience was Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State, George P. Schultz. A capital campaign for a new building associated with the Hoover Institution is being conducted and will be named for Schultz.

The panel’s topic dealt with “One Hundred Years of Democracy and Foreign Policy” in which Rice probed the issue, among other questions, whether the establishment of democracies in foreign countries should be a U.S. policy objective. Krasner said after World War II, when Japan was under American administration, the creation of democracy was a top objective, and it was successful. Ferguson said that the U.S. had continually put pressure on the Soviet Union to democratize, contributing to its break up into a collection of former Soviet states, some of them pro-Western. He said the U.S. must continue to stand on the side of individual freedom. Both men indicated that the next great test for democracy will be whether China can survive as an authoritarian regime.

When it came time for questions and answers, a member of the audience asked how the United States could claim, on the one hand, that it supports human rights and on the other give a pass to the leaders of Saudi Arabia after the Oct. 2 murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi embassy in Turkey. Rice took that question, saying that was the kind of dilemma that makes a U.S. Secretary of State want to go back to bed. The U.S. has values, but it also has interests, she said. If the U.S. had cut off relations with Saudi Arabia following Khashoggi’s murder, it would have weakened Saudi Arabia, but at the same time would have greatly benefited Iran, which is a prime U.S. adversary.

In a brief discussion about the Middle East that ensued, Ferguson asserted that Israel’s development of improved relations with Saudi Arabia and a number of Gulf States can be considered, in part, one of the successes of U.S. policy.

The next panel, on April 18, will feature Schultz, who is a Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow at the Hoover Institution, along with panelists Terry L. Anderson, John F. Cogan, and Lee Ohanian in a scheduled 90-minute discussion on “A Century of Prosperity: Improvements in the Standard of Living, 1919-2019.” Subsequent panels will deal with “threats to free and open societies”; “Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill during the Second World War;” “Changing the Education Debate,” “New Regional Orders,” “Tax and Monetary Reform; “ “Hoover’s One Hundred Years of War, Revolution, and Peace,” “Labor and Capital Market Policy,” and “A Century of Citizenship and the Constitution.”

The 2018 annual report of the Hoover Institution makes reference to the Middle East, noting that its Herbert and Jane Dwight Working Group on Islamism and the International Order publishes the online journal The Caravan, which analyses Islamic movements in Iran, Syria and Southeast Asia, and suggests ways that the U.S. might recalibrate its Mideast policies in response.

At its Washington D.C. branch, Hoover Institution Fellow Adam J. White last year hosted U.S. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) for a panel discussion with Rabbi Meir Soloveichik of New York City’s Congregation Shearith Israel “that focused on the proper relationship between religion and government and the contribution that Judeo-Christian ideas have made to American political thought.”

Tad and Dianne Taube Senior Fellow Peter Berkowitz is quoted in the 60-page annual as declaring “The real protection of or freedom is the prevention of abuses of power.”

*

Harrison is editor and Masori is a staff photographr of San Diego Jewish World. They may be contacted respectively via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com and shor.masori@sdjewishworld.com