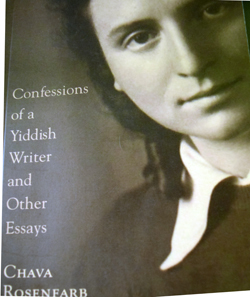

Confessions of a Yiddish Writer and Other Essays by Chava Rosenfarb, McGill-Queens University Press © 2019, 282 pages including appendix and index.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Chava Rosenfarb was recognized as a novelist and essayist of substance by those of the post-Holocaust, shrinking, Yiddish-speaking world, but it remained for her daughter, Prof. Goldie Morgentaler, to bring her works to life in English.

SAN DIEGO – Chava Rosenfarb was recognized as a novelist and essayist of substance by those of the post-Holocaust, shrinking, Yiddish-speaking world, but it remained for her daughter, Prof. Goldie Morgentaler, to bring her works to life in English.

Morgentaler, a professor of English and Yiddish literature at the University of Lethbridge in Canada, had already translated her late mother’s three-volume work, The Tree of Life, which detailed life and death in the ghetto of Lodz, Poland. To that monumental work, she now has added this book of essays, in which Rosenfarb reflects on her post-war life in Canada, her mourning for the increasingly less influential Yiddish language, her observations as a literary critic, and her joy as a travel writer set loose in Australia and the Czech Republic.

From the outset of the book, I found myself cheering her felicity of phrase and the depth of her intellect.

Just two paragraphs into the title essay, I grabbed my marker pen and underlined the following: “No matter what the subject, all literary roads lead back to the self. The writer descends like a miner into the deepest shafts of her soul in order to unearth the blackest coals of her torment, or to retrieve the most glittering diamonds of her memories, and bring them back to the surface in the form of fictions that she wishes to share with the world.”

Confined to the Lodz Ghetto until she was transported to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, she recalled that “in the ghetto, along with tuberculosis, typhus and dysentery, there raged the epidemic of writing. The drive to write was as strong as the hunger for food. It subdued the hunger for food. Each writer nurtured the hope that his or her voice would be heard. It was a drive to raise oneself above fear through the magical power of the written word, and so to demonstrate one’s enduring capacity for love, for singing praise to life. Even in the concentration camps, even by the glare of the crematorium flames, there were those who wrote.”

This led her to conclude that “as long as there is life, the human heart will never cease singing of its joys and sorrows. Up to the brink of the grave, man clings to his songs, just as he clings to life.”

One of Rosenfarb’s great disappointments was that the world failed to recognize the moral imperative of the Holocaust.

“When we were in the ghettos and the concentration camps, it seemed to us that we were the collective Isaac; lying on the sacrificial altar of the world, and that with our sacrifice we were ensuring a better future for our people and for humankind as a whole; after us would come a breed of men and women who would be good and would have it good. We hoped that after the storm the world would be cleansed of hatred, and that there would be brotherhood between the peoples of the world. This hope helped us live –and it help us die. How naïve we were and how bitter has been awakening … After the horrendous cataclysm, everything reverted to business as usual, as if nothing had happened.”

After some chapters about her life and about those of the writers Paul Celan, Stephen Zweig, Sholem Asch and Isaac Bashevis Singer, there came Rosenfarb’s essay on feminism and Yiddish literature.

“The Jewish male, so exalted and praised in the Scriptures as the son of God’s chosen people, suffered terrible blows to his manhood at the hands of his hostile non-Jewish neighbours,” she wrote. “Although heroic in his perseverance and determination to protect his existence and his way of life, he was for the most part deprived of any effective possibility for doing so. In order to save his soul and often his life, he was forced to surrender, to submit in a way usually associated with women.”

The only masculine pursuits available to the Jewish male, under such circumstances, were learning and being the head of the family. “Excluded from the brotherhood of those who studied God’s word, the Jewish woman was reduced to being a kind of benign, resourceful golem – a workhorse with a tender, ever-loving heart, a never-resting womb, and hands that were never idle. In the sphere of Jewish social life, it was she who assumed the role of oppressed Jew vis-à-vis the Jewish male—and was thus burdened with a double load of suffering.”

In another chapter, dealing with the rigors of literary translation, she observed that “English frowns on redundancy; Yiddish thrives on it. Nobody ever just cries in Yiddish; they cry with tears, they cry out their eyes, they cry so as to sink a ship with buttermilk. Curses are never short and cutting in Yiddish, they are long, involved, and often very funny. The curse is deliberately made fantastical, because it is never meant to come true. For instance, ‘a thunder should enter you through the ears; it should polish your intestines until they shine and leave through your feet, after which, you should swallow an umbrella and it should open inside you.’”

Every page, it seems, is imbued with Rosenfarb’s love of writing and her equal love for learning.

I was delighted by her description of Jewish audiences in Melbourne, Australia. “In the past,” she wrote, “a lecture had to last two hours, with a break in the middle. Now the audience sits still for no more than an hour and a half, with a break in the middle. A friend of mine, a naïve New Yorker, who was invited to Australia for a series of lectures, told me that, accustomed as he was to impatient New York audiences, and wishing to find favour with his Australian listeners, he made his first lecture short, no more than one hour. After he finished speaking, the audience stayed put, awaiting the second part. When it became clear that there would be no second part, they were bitterly disappointed. The lazy speaker was invited to a meeting, at which he was appropriately reproved, and thenceforth adjusted the length of his speeches accordingly.”

When Confessions of a Yiddish Writer and Other Essays came to its end, I felt much like that Australian audience. Perhaps I had no right to it, but I would have liked the book, already substantive, to have offered more and more.

Kudos to Goldie Morgentaler for resurrecting in English her mother’s Yiddish brilliance.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com