Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in our World-At-Home series, in which we endeavor to show that one can travel to every country of the world without ever leaving San Diego County – provided that one is willing to attend lectures, visit museums, go to ethnic festivals and take advantage of other diverse and manifold activities and resources within the San Diego region. In our first installment, we “visited” Mexico by attending a Cinco de Mayo celebration at Grossmont College in El Cajon. Our conceptual route now takes us to the nation of Belize on Central America’s Atlantic coast.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—Archaeology Professor Joseph W. Ball of San Diego State University is a man who appreciates both archaeology and tourism. Unlike some of his colleagues, he doesn’t view the two activities as being in conflict, but rather as complementary.

Yes, tourists might sometimes wander off approved paths at archaeological sites, or be less than careful with their litter, but they are not nearly so troublesome, nor malicious, as looters who try to dig up artifacts at unattended sites. A steady supply of tourists prompts the hiring of staff members, who in turn can protect archaeological treasures from such marauders.

Ball recently agreed to an interview at a café near the Museum of Man, where he is an advisor on exhibits about the Maya culture. He said because of the revenues that tourism can earn, countries like Belize are incentivized to develop high-quality attractions such as the archaeological park and ecological reserve at Cahal Pech, which he and his wife Jennifer Taschek, a fellow SDSU archaeologist, helped to restore.

Cahal Pech is a five-acre site sitting atop a mesa near the town of San Ignacio in the Cayo district of Belize, not far from the small country’s western border with Guatemala. Around the five-acre site, the government of Belize now maintains a 60-acre tropical hardwood forest as an ecological reserve, a vestige of the woodlands that once covered western Belize before they were cut down by loggers and then converted into pasture land by ranchers. In the forest, one will find troupes of howler monkeys, numerous varieties of birds, and a field guide’s worth of flora. There is plenty for visitors to see and for knowledgeable guides to explain.

Before Maya civilization mysteriously collapsed in the 9th Century of the Common Era, kings and queens reigned both as political figures and as intermediaries between the people and their ancestors. A king, known as the kül ajaw or holy lord, kept his private residence at Cahal Pech (a decidedly non-regal name given by latter day archaeologists, meaning “place of the ticks”) and held public ceremonies at the Buenavista del Cayo complex, four times as large, that spread along the banks of the Mopan River, about four miles to the west.

The archaeologist estimated that the between 80 and 120 people lived with the king at Cahal Pech, whereas the population of Beunavista was somewhere between 200 and 300. The king and his court ruled over a farm population that numbered somewhere between 6,000 to 8,000 individuals, Ball said.

Ball and his archaeology students from San Diego State University studied the relationship between the large Buenavista del Cayo site and the smaller Cahal Pech site, and found that the royal residential quarters at the two locations were interchangeable—not only built exactly the same, but also decorated in the same manner. The big difference between the two residences was in its garbage pits—where the archaeologists learned that the royal diet varied according to the season.

Because it was up on a mesa 360 feet higher than the river bank, Cahal Pech generally experienced weather that was 12-degrees Fahrenheit cooler than that at Buenavista del Cayo, according to Ball. By studying “visible botanicals, food remains and faunal remains, the bone residue from meal preparation,” his student archaeologists determined that the king spent the dry season up at Cahal Pech and the rainy season from October to February down by the river. “Shielded by low lying hills to the immediate north,” the Buenavista de Cayo site “doesn’t get the heavy rainstorms that usually come during the rainy season and you actually get a kind of toasty feeling there,” said Ball.

In the rainy season, the king and his court typically ate river fish, turtles and tamales, while in the summer, they ate more venison, birds and small animals, said Ball.

By the way, said Ball, if you want a good tamale, you have to try one in Maya country. “It’s a Maya invention, a Maya creation that spread through the rest of Mesoamerica,” he said. “They make the best tamales to this day—with plantain and banana oil!”

*

One of the most important ceremonies that occurred at the Buenavista del Cayo complex was when the king participated in what is called “auto-sacrifice” – that is letting his own blood – in order to induce a vision and communicate with the Maya ancestors. This ceremony typically would occur at the top of the staircase of the ancestor monument, inside which important forbearers were buried. The people, looking up from a large plaza, would watch as the king would take an obsidian knife, and puncture his own penis, so that his genital blood would drip onto bark paper.

The procedure produced a lot of blood but relatively little pain, and “shedding blood is a good way to get to a visionary state without taking any hallucinogenic substances,” according to Ball. When queens ruled, they cut their tongues with thorny thongs to get her blood onto the bark paper. Rulers of either gender would also shred their ears to produce the blood.

Afterwards, the bloody bark was burned and the smoke ascended to the sky, whereupon the king would have a vision, in which the ancestors gave advice concerning whether he should lead his people into war against neighbors, or other such important questions of public policy.

Both Cahal Pech and Buenavista del Cayo have ball courts at which another important Maya ceremony was conducted. To understand the importance of the game, said Ball, a Roman Catholic, it’s helpful to consider the meaning of a Roman Catholic mass, in which the Blood and Body of Christ are served to those taking communion . In the Roman Catholic view, this ceremony is not a symbolic reenactment of the events of the Last Supper, but, in actuality, is a “physical reoccurrence – if you are a devout Catholic, you believe quite literally that what is happening is magical, and that, in fact, there is a literal reoccurrence of the Last Supper.”

The ball game played between a three-member team led by the kül ajaw, and another team, led by a captured (and weakened) king from a neighboring polity, was understood by the Maya to be a reoccurrence of the events surrounding the creation of the world and the production of corn in their centuries-old Creation Tale, according to Ball.

The archaeologist said that in the Maya belief “Lords of the underworld,” killed a man and his brother who strayed too close to the underworld and then hung their heads on a calabash tree. As a young woman passed under the tree, the head of the man spit, causing her to become pregnant. Eventually she delivered twins, who were raised in secret by their mother and grandfather. When they grew, they were told to retrieve their father’s body and avenge his death. Doing this required them to avoid fatal traps and to succeed at a variety of tasks that the lords set out for them.

Fascinated by the ball game that the young men played, the lords of the underworld required the two brothers to play against each other, with the loser to be put to death. However, three days after one brother was decapitated, he came back to life. That prompted a desire among the lords of the underworld to experience resurrection for themselves. They played and lost the ball game to the brothers. However, when the brothers killed the lords, they did not bring them back to life.

According to Ball, this story of good defeating evil explains to Maya the origin of the sun and the moon. When the father’s body was brought home, it turned into corn.

When the kül ajaw played the ball game, it was understood not as a reenactment, but as the actual repetition of the Creation story, a repetition that assured the success of the people of his territory. So that there would be no unforeseen outcomes, Ball said, the captive king was intentionally weakened before the contest, not unlike the way the evil Roman Emperor Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix) weakened Maximus (Russell Crowe), the general-turned-gladiator, before their contest in the 2000 movie, Gladiator.

In a side discussion, Ball dismissed the current popular furor over a supposed Maya prediction that the world is set to end on December 21, 2012. He said the speculation began after a “single fragmentary inscription in which this date is mentioned” was found at Tortuguero, Mexico, which said that on this date “a great event will transpire.” Because the “great event” coincides with the date that the Maya calendar ends one cycle and is about to start another, some people have sensationalized this message into an end-of-days prediction. Ball said the change of the Maya calendar from one cycle to another has happened before and is similar to the odometer on a car changing from 999,999 to 000,001.

*

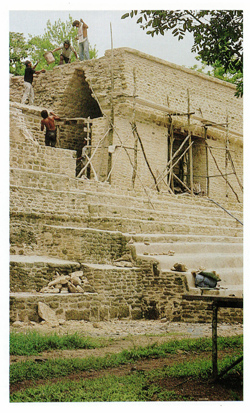

During the course of their studies of the site, Ball and his wife Jennifer, who is an architect and field archaeologist, noted that “Maya foundations are a problem, you have this city on tropical soil, terrible … so we put in a real foundation, with rebar, concrete, etc., and then (after dismantling the site stone by stone and creating a reverse blue print of the structure) we put back what was there,” Ball said. “So what you wind up with is a restoration of what was there, only done with modern materials and safer – safe for the tourists and safe for the site.”

Ball contrasted the Cahal Pech restoration with reconstructions in other parts of the old Maya empire where countries would simply “reconstruct everything whether they knew what was there or not, and they would take out every tree, bush and shrub, so all that would be out there is a series of reconstructed buildings.”

Besides persuading the Belize government to restore rather than reconstruct the site, said Ball, “the second thing that we argued for is don’t take out all the trees, don’t trash the environment. Instead combine eco-tourism and archaeo-tourism in the same place. Treat these as mini-nature reserves, keep specimen trees, and let them provide shade. Don’t pave over the plaza, leave it grassy. People are going to come for picnics, they will enjoy it. Put in trails, mark the trees, have guides who know the local animals…”

When work began on the restoration, Ball said, it was quite controversial, in part because the project was being run by Americans, and Americans would get the credit. Among parts of the population in Belize, he said, there is quite a bit of xenophobia. Outsiders are resented.

Nevertheless, the work proceeded under the protection of the Ministry of Tourism, and over the years, the site gained in popularity. Now, Ball said, it is a top spot for weddings and birthday celebrations, whether the families are from the ruling class or from among the poorest people. San Ignacio has gained sufficient population to become Belize’s second largest city after Belize City, and tourism has climbed from the country’s tenth-most important economic generator to its largest.

To visit the site, one either rents a car or goes by tour bus to San Ignacio, a three-hour drive along the western highway, Ball said. He recommended that tourists proceed directly to San Ignacio and avoid Belize City because of the latter’s high crime statistics. Hotels in San Ignacio, he said, are very nice.

From San Ignacio, one should take a taxicab up to Cahal Pech, a ride that typically costs $5 U.S.. The cab will drop visitors off at a museum, in which artifacts including a Maya skeleton are displayed, and maps help visitors understand the layout of the site. The museum charges another $5. The walk from the museum to the entrance is perhaps 300 yards, and from there visitors go into the main plaza, see the ancestor monuments and the Audiencia, which was similar to a reception hall. They will pass through the reception hall to the living quarters, and will follow a labyrinthine three story stairway by which servants must have delivered food and water to the royal family. Inside the family compound, one will see empty rooms with sleeping benches, but without any artifacts. Eventually, the tour will lead to a burial structure in which bodies date back to 900 years before the common era – “the oldest burials in Belize,” Ball said. There are steles on the site – but unlike those at San Diego’s Museum of Man, which are carved – these are painted without the hieroglyphs. There is also a Maya ballcourt and a sweat bath, which was used after the games.

The tour, with explanations from the guide, takes about 90 minutes, Ball reported. There is no restaurant at the site and no gift shop featuring the work of Maya artisans. Those may be found below Cahal Pech, in the town of San Ignacio.

Ball said he hopes eventually a gift shop and restaurant will be constructed on the site, but he no longer is in a position to greatly influence that decision. The government changed hands, the ministry of tourism staffed with new personnel, and the Balls’ secondary assignment as tourism consultants was completed. For a decade now the couple has been addressing themselves to their first love: archaeology. Ball said he takes students from San Diego State University down to San Ignacio most summers to analze and catalogue artifacts from the Cahal Pech site that are stored there.

The archaeologist said in addition to such “laboratory” work, he continues to study the Maya political system – one which he describes as “segmentary,” meaning that weaker kings could attach their territories to those of more powerful kings, and at times, detach and reattach them to the territories of other powerful kings.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish world. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com