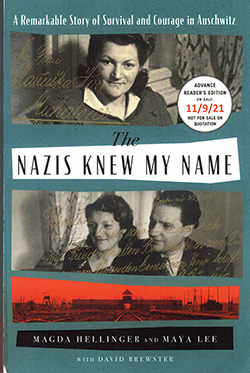

The Nazis Knew My Name by Magda Hellinger and Maya Lee (with David Brewster); Atria Books, (c) 2021; ISBN9781982-181239; 310 pages; $27

SAN DIEGO — If you hear of a Jew appointed to a position of authority at one of the Nazi concentration camps, what word comes immediately to mind?

SAN DIEGO — If you hear of a Jew appointed to a position of authority at one of the Nazi concentration camps, what word comes immediately to mind?

Is it “collaborator?”

In The Nazis Knew My Name, the late Magda Hellinger tells of her experience being appointed first as a block leader and later as a camp leader by the Nazis during her three-year incarceration in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp complex. She relates that it was never her choice to be a block or camp leader, and that had she refused, she most likely would have been severely disciplined or sent to the gas chambers. As a leader, she was expected to keep order in the block, and later in a full camp — or else. Rather than being a collaborator, Hellinger — a former Zionist youth leader and kindergarten teacher — portrays herself as an ever-alert intermediary, trying to better and prolong the lives of as many concentration camp victims as possible.

She and her daughter Maya Lee offer numerous testimonies from other prisoners about her kindness, which frequently manifested itself in calls for everyone to help each other to survive and arranging, through organized theft, for extra food and clothing for the prisoners. She helped save the lives of some lame women by assigning them to details — such as kitchen duty — which would excuse them from the interminable roll calls of which the Nazi guards were so fond. People who obviously were sick or crippled often would be pulled out of the roll call formations and sent to the gas chambers.

Among those whom she protected and found safer jobs for were numerous members of her Slovakian Jewish family, so many that it would be hard for her to defend against charges of favoritism.

Nevertheless, her kindness to many others was well documented.

Hellinger relates incidents in which she had to slap prisoners for their own good. One example was a woman who unwittingly volunteered for a promising-sounding “assignment” that Hellinger knew was a Nazi trick. Anyone who went on the assignment would be sent straight to the gas chambers. She pulled the woman away and pretended to scold her for deserting her current situation, slapping her for emphasis. The woman had no idea that her life had just been saved, and held the incident against Hellinger for the rest of her life, even taking her to court over it. The judge ruled in favor of Hellinger and chastised the complainant.

As a leader, Hellinger tried to assure fair distribution of the meager portions of soup that were allotted to the prisoners. When a woman crashed into a line and dipped her bowl into the pot, thus disrupting the distribution, Hellinger slapped her. That woman too brought complaints against her, again to no effect.

Hellinger came into contact with some notorious Nazis, among them the SS Guard Irma Grese, to whom she had to report. Grese, who was executed after the war for her sadistic and murderous conduct, was nicknamed “the beautiful beast.” Whenever she lost her temper, which was often, she would use her whip on prisoners. Somehow Grese, who was younger than Hellinger, took a liking to her, telling her about her personal life and asking for advice. According to Hellinger, that enabled her from time to time to appeal successfully to Grese in behalf of prisoners. Alas, she could help some, but not all.

Another Nazi SS Guard was Luise Danz, who like Grise used to whip prisoners. But whereas Grise did it only when she was angry, Danz did it on a regular basis, victimizing random prisoners. Hellinger said she devised strategies to keep Danz from patrolling the camp. She had one prisoner with a background in art make a portrait of her, requiring many sittings. Another prisoner pretended to read Danz’s palm, telling her that her brother on the Russian front was very worried that she would be punished at the end of the war for the way she treated prisoners. According to Hellinger, Danz softened after that. After the warDanz was tried and sentenced to life imprisonment.

This memoir provides a different view than most of life in the notorious Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps. As a result, it adds to our collective knowledge of the Holocaust.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com