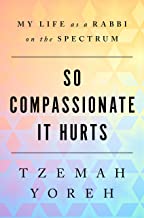

So Compassionate It Hurts: My Life as a Rabbi on the Spectrum by Tzemah Yoreh; Modern Scriptures (c) 2022m ISBN 9798836-444075; 153 pages; $19.99.

SAN DIEGO — Tzemeh Yoreh is a rabbi of the Jewish Humanism movement who leads the City Congregation of New York City.

SAN DIEGO — Tzemeh Yoreh is a rabbi of the Jewish Humanism movement who leads the City Congregation of New York City.

By his own assessment, being a rabbi who must give sermons before a congregation and empathize with congregants during times of their loss or emotional stress is a challenge that others might believe insurmountable given his high-functioning autism.

Yoreh is book smart–I’m tempted to write “brilliant”–having earned doctorates first in biblical criticism from Hebrew University in Jerusalem and later in Ancient Wisdom Literature from the University of Toronto.

In addition, Yoreh is a poet able to compress abstract ideas into structured formats.

Structure and routine are very important to Yoreh but as anyone knows who belongs to a Jewish congregation, change can come from many sources — the pressure of events outside the synagogue, clashes of personalities within it, as well as rabbinical innovation which may or may not be acceptable to the congregants.

One facet of Yoreh’s autism is difficulty understanding social cues whether they be verbal or expressed through body language.

He has no tolerance for falsehoods — “white lies” or otherwise–and he is practically incapable of modulating his voice. People may think he is screaming, while he is simply trying to communicate.

Yoreh is keenly aware of all these traits and works hard to moderate them. What apparently makes his congregation so accepting of him is his strict emphasis on fairness towards all people and the intellectual honesty with which he presents his thoughts.

The rabbi became art of the Humanist movement because he cannot believe anything for which there is no proof — an unknowable God for instance.

He wavers between atheism and agnosticism.

He is unafraid of taking political positions. Trimming the sails of his opinions simply is not in his makeup.

The rabbi has a child who is “deeper” on the autistic spectrum. At the time of publication, his elementary school-aged son hadn’t spoken a word for years.

This has prompted deep reflection on Yoreh’s part. He knows how he himself likes to be treated by others, but just as neurotypical people don’t quite understand his way of thinking, nor his needs, he intuits that neither can he know for certain the desires and needs of his son.

Yoreh’s memoir challenges readers to think deeply about issues, emotions, and human interactions. One reason the book is appealing is that the rabbi is uncompromisingly honest about himself.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com