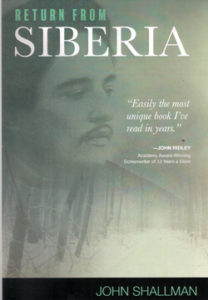

Return from Siberia by John Shallman, Skyhorse Publishing © 2020; ISBNB 9781510-763371; 220 pages including acknowledgments.

SAN DIEGO – Author John Shallman is a Los Angeles-based political consultant and commentator, and one of the protagonists in this novel is John Simon, a political consultant. There is no coincidence here; the book is a thinly disguised memoir with elements of fiction thrown in.

SAN DIEGO – Author John Shallman is a Los Angeles-based political consultant and commentator, and one of the protagonists in this novel is John Simon, a political consultant. There is no coincidence here; the book is a thinly disguised memoir with elements of fiction thrown in.

The plot runs something like this: the family of John Simon finds a book in Yiddish that was written by John’s great-grandfather, Yosef Rakow, which told how Russian workers were oppressed during the time of the Czar. Even as a young teenager, Yosef understood the injustice of it all, eventually becoming involved in revolutionary politics, which led to a 10-year term of imprisonment in Siberia, far from his family members, who meanwhile made it to freedom in America.

Shallman juxtaposes this story with a modern one: a campaign in Texas in which John Simon serves as a consultant that pits Patti Alvarado, a former undocumented immigrant from Mexico who became a U.S. citizen by virtue of marriage, against a White racist congressman. The incumbent utilizes many dirty political tricks in an attempt to demonize Alvarado along with other immigrants.

Shallman draws parallels between the czarist oppression of the underclasses with today’s racism and economic exploitation of minorities in the U.S.

As the story proceeds, we learn of Yosef becoming infatuated with Rosa, a fiery socialist who also was exiled to Siberia. In the roughly parallel story, Yosef’s modern-day namesake, Joseph, studying for his bar mitzvah, is all agog over a beautiful classmate whose bat mitzvah is scheduled the same day as his, and who, thus, will share the bima with him on their big day.

Meanwhile, another of John’s children, his daughter, has fallen in love with a gentle Iranian Muslim, who suddenly is deported under draconian immigration laws promulgated during George W. Bush’s administration and enforced zealously by Donald Trump’s.

Eventually, Yosef completes his ten years of exile, where he learned from an indigenous Kaldean woman that “the only way to survive the merciless Siberian winters was to embrace them fully, to become deeply present, even curious about the darkness, biting cold, the stillness, absence of color, the monotony, and the boredom. Redemption came from accepting all of it as the grace and rhythm of nature, rather than wasting mental energy longing for the thaw.”

In contrast, as Yosef proceeded to his home in Pinsk, and thence to London, New York, and Chicago in an effort to find his family, what he could not “embrace fully” was early 20th century Western European and American capitalism in which laborers were exploited by business owners. He became a union organizer, and, one day he learned that one of the construction companies exploiting workers was owned by none other than his long-lost brother.

How the family is both bound by love and riven by rivalries – similar to young Joseph’s Torah portion about Jacob and Esau – is an important part of this memoir/ novel.

Along the way, Shallman drops the names of many historical figures who Yosef allegedly met during his travels, among them, Josef Stalin, Rosa Luxembourg, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and Clarence Darrow.

Overall, the book made for fast reading. In my opinion, the memoir/ novel had too many subplots, allowing Shallman too little time to fully develop his characters. This possibly was the result of Shallman wanting to put nearly every member of his family, or a counterpart, into the book, and also his desire to construct the plot to make political comparisons between the early 20th and 21st centuries.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com