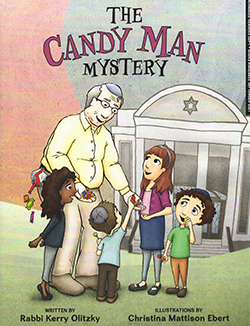

The Candy Man Mystery written by Rabbi Kerry Olitzky, illustrated by Christina Mattison Ebert; Kalaniot Books, 2021; ISBN 9781735-087528; 24 pages including appendices; $19.99.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Rabbi Kerry Olitzky, author of The Candy Man Mystery, is primarily known as a Jewish educator having served as a dean at the Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion and as a vice president of the Wexner Heritage Foundation. Perhaps, however, he was remembering his 15 years at Congregation Beth Israel in West Hartford, Connecticut, when he wrote The Candy Man Mystery, a book likely to intrigue elementary school-aged children about synagogue Judaism.

SAN DIEGO – Rabbi Kerry Olitzky, author of The Candy Man Mystery, is primarily known as a Jewish educator having served as a dean at the Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion and as a vice president of the Wexner Heritage Foundation. Perhaps, however, he was remembering his 15 years at Congregation Beth Israel in West Hartford, Connecticut, when he wrote The Candy Man Mystery, a book likely to intrigue elementary school-aged children about synagogue Judaism.

In this story, enhanced by Ebert’s vivid illustrations, young Josh Stein bolts into the sanctuary of his synagogue, before Shabbat services even start, because he is hoping to sit next to Mr. Sharansky, a grandfatherly immigrant from Russia who never fails to have candy in his pockets for the children. Sharansky is well liked because he tells the children silly jokes, and appreciatively accepts their corrections of his English. When he’s not entertaining the children, he volunteers as the synagogue’s handyman, or as a cook in the kitchen, or as an aide to his wife, who runs the synagogue’s gift shop. He’s a true mensch, in other words.

But for some reason, Mr. Sharansky is not in the sanctuary on this day. So Josh and his older sister Becky run to Cantor Cohen’s office to see if she knows where he is. She doesn’t, but she takes the time to teach Becky and Josh a Russian melody for singing Adon Olam (Lord of the Universe). Next the brother and sister look in the room where the junior congregation is meeting, but Jody Kaplan, the teen leader hasn’t seen him. However, while Josh and Becky are there, she teaches them how to say the Shema (Hear!) prayer in American Sign Language.

The children head for the social hall, where some of Mr. Sharansky’s friends like to have coffee before services, but, no, he’s not there either. Finally, they go to the office of Rabbi Susskind, who is getting ready to start the service. He explains to the children that Mr. Sharansky had taken ill the previous evening and was taken to the hospital, where he was expected to recover quickly. The children decide with their parents, who were awaiting them in the sanctuary, to visit Mr. Sharansky at the hospital. They bring him candy, sign the Adon Olam to a Russian melody, and demonstrate how to sign the Shema. Of course, Mr. Sharansky is touched by their kindness.

At the end of the book, there is a glossary of terms used in the story, as well as a chart showing the signs one would use for the repetition of the Shema, which states: “Hear O Israel, The Lord Our God, The Lord Is One.” In American Sign Language, it is told with six signs: 1) Pay Attention; 2) Israel; 3) God; 4) Our 5) God 6) Is One.

The beauty of this simple tale is that emphasizes the egalitarianism one might find in a Reform congregation, including a female cantor and a female teen leader and a male rabbi. Children also are introduced to Russian Jewish immigrants, to new prayer melodies, and to a new method of communicating: American Sign Language. The story assures children that they are welcomed, and very much loved, inside the synagogue, even if, like Josh, they sometimes run around in their excitement.

All in all, it’s a book that is both warm and inviting for young readers.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com