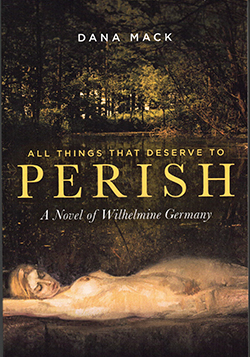

All Things That Deserve to Perish by Dana Mack; 2020; ISBN 9781735-302607; 337 pages including afterword, acknowledgments, and Book Discussion Questions.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — The book cover gives a false impression of the contents of All Things That Deserve to Perish. While there are sexual situations that contribute to the outcome of the story, the major theme of this book is the toxic relationships between Jews and German Christians at the fin de siècle.

SAN DIEGO — The book cover gives a false impression of the contents of All Things That Deserve to Perish. While there are sexual situations that contribute to the outcome of the story, the major theme of this book is the toxic relationships between Jews and German Christians at the fin de siècle.

In particular, the novel paints a story about Elisabeth von Schwabacher, a talented concert tour-ready pianist who is the daughter of a wealthy Jewish banker, and Count Wilhelm von Boening, a member of the landed nobility (Junkers) in Prussia. While his family has plenty of inherited land and is responsible for the upkeep of residents of an associated village, it was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Faced with the choice of either selling off hereditary holdings or marrying wealth, Wilhelm, like other nobles in his class, sets his sights on finding a suitable wife who could bring a large dowry. Elisabeth (Lisi) more than fit the bill because in addition to being an heiress and a talented pianist, she was well-read and towering in intellect.

But what might attract her to him? He was reputed to be one of the most handsome bachelors in Germany, and the woman who married him would automatically gain the title of countess (gräfin in the German language). On the other hand, both fathers were vehemently opposed to such a marriage. Her father knew that to marry a count, Elisabeth would first have to convert to Christianity. His father didn’t like Jews, converted or otherwise.

In fact, Wilhelm’s attitude towards Jews reflected his father’s and his peer group’s unabashed antisemitism. He bought into and often repeated the tropes of Jew hatred and yet he was bedazzled by her. Elisabeth knew of his family’s prejudices, but nevertheless felt herself undeniably attracted to Wilhelm. She excused his anti-Jewish prejudice as relatively unimportant given his apparent love and tenderness toward her.

Throughout the novel, whose author is herself Jewish, one encounters the taunts, the sneers, and the threats from German Christians against the Jewish people, presaging the Nazi era in Germany which would come some 30 years later. We learn from the German perspective how envy, jealousy, and feelings of inferiority lead to Jew hatred. In Wilhelm’s view, for example, “The Jews are always bragging and showing off in some way or other. Always reaching for some performance or feat, always working so zealously to be remarkable. Always searching for the next thing, and never accepting the thing that is. And that is why people hated the Jews … and were even beginning to talk of destroying them. Because everywhere the Jews wanted to be noticed. And the desire to be noticed is, after all, an obnoxious thing.”

There is, of course, a parallel in this late 19th century tale to the situation Jews face today with antisemitism on the rise all over the globe. We must know that when we brag about how many Nobel Prizes we have won, or the great medical achievements credited to our people, or how wonderful is our philanthropy (as testified to by our names on buildings, plazas, and programs), that not everyone will be appreciative or consider themselves better off because of our achievements. Instead, some will feel diminished and resentful.

So, what is the answer? Is it to convert to the majority religion wherever we might live, as characters in this tale did? Is it to stand apart from the rest of the world, move to Israel, and declare “our critics be damned”? Or is the answer in finding some middle ground, including being more modest about our achievements (Maimonides thought that charity is better delivered anonymously, so that neither donor nor recipient would know each other’s identity) while quietly helping others to reach their full potential?

Such questions are of far greater import than what is intimated by the cover designer of this novel.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com