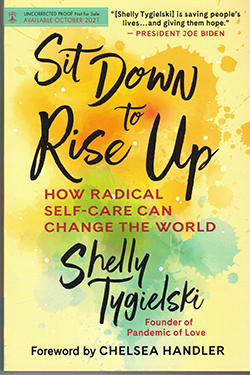

Sit Down to Rise Up: How Radical Self-Care Can Change the World by Shelly Tygielski; Novato, California: New World Library (c) 2021; ISBN 9781608-687459; 223 pages plus afterword, sources and acknowledgments, $25.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Israeli-American Shelly Tygielski is the founder of the “Pandemic of Love” movement, which champions people reaching out to each other, happy to give help and unafraid to ask for it. However, before one can help others, one might need to engage in self-help, getting one’s priorities right, and, as the slang saying puts it, getting one’s head on straight.

SAN DIEGO — Israeli-American Shelly Tygielski is the founder of the “Pandemic of Love” movement, which champions people reaching out to each other, happy to give help and unafraid to ask for it. However, before one can help others, one might need to engage in self-help, getting one’s priorities right, and, as the slang saying puts it, getting one’s head on straight.

For author Tygielski that meant dealing with an eye disease that threatened to blind her, divorcing a husband, readjusting to life as a single mother, and quelling her desire, born of insecurity, to strive for approval by trying to always be the best. To deal with this, she wrote out questions and answers about what she needed to do to improve her life on a course that eventually led to meditation.

She realized that with eye problems, a young son to raise, setting up a new household, and working in a demanding career, she was having trouble doing it all. She gathered together some acquaintances and admitted to them that she needed help. So too, she understood, did every other woman in the group, in one way or another, also need help albeit of different kinds tailored to their individual needs. The women decided they could help themselves by helping each other; that their group — I’m tempted to call it a “chavurah” — could become a community of caring. This led to carpools, shopping for one another, and lending each other an ear when someone just needed to talk.

Tygielski later expanded upon her idea of creating community. Utilizing social media, she asked who might want to join her on a South Florida beach to meditate on a certain day. As it turned out, the day in question was blustery, with rain most likely. But she went to the beach anyway and a cadre of people showed up, undeterred by the weather. Happy with their meditation experience, they told others, and the movement over the months mushroomed. According to Tygielski, as many as a thousand persons at a time plopped their blankets on the beach to participate in guided meditations.

Tygielski was very moved by mass shootings at the Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland and the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando. Her large meditation group had been purposefully apolitical, but after those shootings, she felt she had to say something about the need to keep guns out of the hands of people with mental instabilities, and to ban certain weapons altogether. She feared that speaking out might cause dissension — and some people indeed were upset — but for the most part her decision led her to even greater activism.

She became involved in women’s marches and gun control advocacy. When COVID-19 sidelined many people from their jobs, she conceptualized a pandemic of love, in which people who needed help would receive it from people who had the resources, energy, and willingness to provide it. She asked on social media for people to fill out forms, one indicating what kind of help they needed; the other indicating what type of help they might be able to provide. The response was so massive that Tygielski had to recruit volunteers to handle the volume of participants and to help match recipients with donors.

Tygielski preaches that enmities can be overcome with simple kindness. She tells of a time as a young girl that she got lost in Jerusalem’s Old City, having turned from the Jewish quarter to the Muslim quarter. She was petrified, imagining all the terrible things that might happen to her, but a young Arab man kindly led her through the maze of streets back to the Jewish quarter. Later in her life, she accompanied some United Nations officials to an Arab village, fearfully anticipating that she would be among people who hated her, especially when she saw a portrait of Yasser Arafat on the wall of one home. Then two small children in the house sought her attention to play with them, and acceding to their wishes, she realized how very much alike all people are, no matter their ethnicities, religion, politics or backgrounds.

Kindness can overcome, she taught one wealthy volunteer from New York, a liberal Jewish woman who was matched via the Pandemic of Love with a white woman living in rural poverty in Alabama. At first the Jewish woman demurred. She thought their differences in background and politics would be too great to form a bond. But by sending books to the children of the woman from Alabama and providing other aid, barriers were broken down and false assumptions demolished. The two women even became friends.

Action is the key to Tygielski’s world. She asked for help when she felt she needed it. She put her idea about a meditation group up on social media. She organized a movement for good people to help each other. Perhaps none of that could have been accomplished if she hadn’t overcome her insecurity and willed herself to take the initiative in reaching out to others.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com