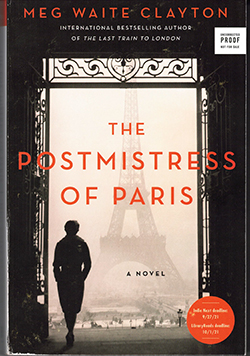

The Postmistress of Paris, a novel by Meg Waite Clayton; HarperCollins (c) 2021; ISBN 9780062-946980; 416 pages, $27.99.

SAN DIEGO — “Postmistress” is a euphemism for “messenger,” which was the role that Nanée, an American heiress, played while in Paris, prior to the German invasion. Initially, she and her compatriots focused on getting well-known artists and intellectuals — many but not all of them Jewish — out of Nazi Germany and into safety in France.

SAN DIEGO — “Postmistress” is a euphemism for “messenger,” which was the role that Nanée, an American heiress, played while in Paris, prior to the German invasion. Initially, she and her compatriots focused on getting well-known artists and intellectuals — many but not all of them Jewish — out of Nazi Germany and into safety in France.

After the invasion but prior to U.S. entry into the war, Nanée’s next efforts were to get herself and her friends out of German-occupied France to the southern part of the country controlled by the Vichy government, where it was thought her friends might be safer.

But such was not universally the case — particularly not for Edouard Moss, a Jew who was a well-known photographer. He subsequently was imprisoned by the Vichy government. At the risk of her reputation and self-respect, Nanée set out to persuade the commandant of the local prison to let Edouard go. The episode raises the issue of how society should judge a woman who prostitutes herself for a noble end, a question that is examined more than once in this novel.

Edouard was a widower, the father of Luki, a charming daughter of pre-school age, for whom Nanée felt unexpected maternal affection. Helping the Moss family, along with other refugees, was an affirmation for Nanée that her life could have importance; that the dull, meaningless, routines of her previous life as a moneyed daughter from Evanston, Illinois, were in her past, not in her present nor future.

After renting a large home in rural Vichy France, Nanée was able to host continuously a network of intellectuals and American rescuers led by Varian Fry, head of the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC). Although non-governmental, the ERC was able to arrange U.S. passports and visas to high-value refugees.

Eventually, however, the Vichy government, prodded by the German Gestapo, began tightening the noose around Nanée and her guests. With her American passport, could she help them flee to Spain en route to Portugal?

In an afterword, author Clayton reveals that while Nanée is a fictional character– as are Edouard and Luki — parts of Nanée’s story were inspired by the real life Chicago heiress Mary Jayne Gold, who worked with the real-life Fry to secret artists and intellectuals out of France.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com