Story by Donald H. Harrison; photo by Shor M. Masori

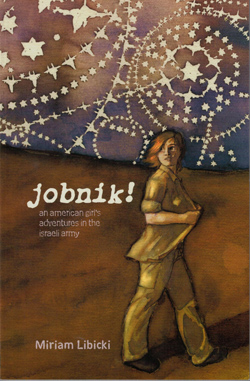

SAN DIEGO – Miriam Libicki, whose graphic memoir about life as a clerk in the Israel Defense Forces was on sale at the annual Comic-Con Convention, has been plunging into issues of personal identity: hers and those of Russian-born friends.

She grew up in Ohio as an Orthodox Jew, made Aliyah to Israel, served in the Israel Defense Forces, returned to North America for university, and now is completing a master’s thesis at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

Since writing the autobiographical Jobnik, she has published a book of graphic essays, Towards a Hot Jew; has married Mike Yoshioka, a Buddhist, and became the mother of two children, ages 5 and 2, who are being raised Jewish, and has interviewed numerous Russian Jewish immigrants to the United States and Israel about their cultural and religious adaptations. Her thesis will be completed as a graphic novel, one of a handful of theses to be submitted in such a format.

“Jobnik,” is a name given by Israeli combat soldiers to those soldiers who hold down desk jobs far from the action. After making Aliyah, Libicki says she wanted to prove herself to be a true Israeli, not just an American tourist, so she signed up for a tour in the IDF. She was sent to a remote base in the Negev, about a half hour from Eilat, where her duties were principally make-work assignments. In the absence of any true purpose, and as part of her coming of age, she and other young soldiers experimented sexually, going up to but not past the limit of her virginity. Libicki draws herself at that time as plump, and not particularly attractive.

“There are some really beautiful women in Israel, so when I was there, I felt pretty unattractive,” she commented during an interview, specifically mentioning Wonder Woman actress Gal Gadot. “I was also very shy and wasn’t comfortable with my command of the language, so I would say that my self-portrait is as emotional as it is a physical documentary.”

Although she occasionally pictures herself in Jobnik as nude and/ or engaged in various kinds of sexual foreplay—which she says was an important aspect of learning who she was—she still follows some Orthodox ritual. Notwithstanding her rejection of the standards of Orthodox modesty, she is shomer Shabbos. In fact, our interview could be scheduled only well after sundown on a Saturday night. Libicki told me that she can candidly draw sexual episodes of her earlier life because today, “I feel like I was a different person, so I could deal with it in a literary way.”

Although she occasionally pictures herself in Jobnik as nude and/ or engaged in various kinds of sexual foreplay—which she says was an important aspect of learning who she was—she still follows some Orthodox ritual. Notwithstanding her rejection of the standards of Orthodox modesty, she is shomer Shabbos. In fact, our interview could be scheduled only well after sundown on a Saturday night. Libicki told me that she can candidly draw sexual episodes of her earlier life because today, “I feel like I was a different person, so I could deal with it in a literary way.”

Perhaps Libicki’s struggle with Orthodoxy began when she learned as a child how much she loved to draw. It was a source of frustration for her that she could not draw on Shabbat. Drawing on other days was one way her parents could keep her calm and well occupied.

“I don’t know that I subscribe to any ideology right now,” she reflected. “Orthodoxy imprinted itself on me, so I don’t feel comfortable unless I am observing certain things. Yet there are aspects which make me uncomfortable, especially the status of women, so I can’t live an Orthodox life either. I guess as far as Orthodox Judaism goes, I can’t live with it and I can’t live without it.”

She added that cultural identity is an important issue in her thesis. “The Russian community is largely secular atheist, and yet they have a strong sense of Jewish identity,” she said. “Cultural Judaism can be a strong identity.”

Although many Americans saw Jobnik as a fairly negative portrayal of the IDF, according to Libicki, it was a source of amusement for the writers of an IDF Magazine. They saw her book as a humorous “outsider’s view” of life in the Defense Forces.

While many of the assignments she received in the IDF were meaningless, in the final analysis, her experience “gave me fodder for comics,” she said. Creating the memoir to explain to North American friends what she did in Israel, the experience of illustrating it made her realize that she could become a cartoonist.

Her IDF experiences occurred in 2000 during the so-called “second intifada” also known as the al Aqsa Intifada, which occurred after Ariel Sharon, then a member of the Likud opposition, made a well publicized visit to the Temple Mount, with results eerily similar to what is currently going on following the murder of two Israeli soldiers and the installation of metal detectors outside the grounds of the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque.

In her book, Libicki pictures herself and other soldiers listening to accounts of the ever more tense situation on the radio or on television. They were as far removed from the action as one could be and still be inside Israel. Asked if being in the deep Negev at this time was a source of frustration, or relief, she answered candidly, “Both.”

What did she hope readers would take away from her book? She responded that she adheres to the theory that the purpose of literature is to create empathy. By telling stories and reading each other’s stories, “you can gain more sympathy for people, more understanding.” Whatever other people’s images of Israeli soldiers might be – heroes, demons – she said she wanted to present them as “just human.”

“The more stories, the more perspective, the more understanding we can have of the world,” said Libicki, who while finishing her thesis teaches art at the Emily Carr Institute, where she earned her bachelor’s of fine art degree.

After Libicki finishes her thesis on the relationship of Russians immigrants both to Judaism and to their new countries, she anticipates returning to her experiences in the IDF. She said she’d like to recapitulate her career in graphic art through her discharge from the service, and her decision to return to North America for her college career.

Libicki also contributes to other graphic works, including A Minyan Yidn in which she was asked by cartoonist Trina Robbins to illustrate one of the stories written by Robbins’ father back in the 1930s about Jewish life in Brooklyn. Her story dealt with a man who got so drunk the day before his retirement from the railroad that he lost the pension he had worked so hard to earn. To discuss that book on a panel was one of the reasons Libicki had traveled to San Diego for Comic-Con.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com