By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – One hundred seven years ago today, on February 14, 1912, President William Howard Taft signed a proclamation making Arizona the 48th State of the Union. The Republican president may have thought that his signature culminated a long fight with Progressive Democrats in Arizona over the question of the independence of the judiciary. He was wrong.

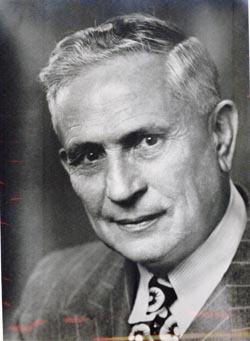

One of Taft’s key adversaries in the fight was Jacob Weinberger, who later would become a moving force in San Diego’s Jewish community as well as the first resident U.S. District Court judge in San Diego.

At the time of Arizona’s 1910 state constitutional convention, Weinberger was a young lawyer living in the mining town of Globe, Arizona. Because of his legal background and because of his friendship with George W. P. Hunt, who had been a territorial legislator and would later become Arizona’s first governor, Weinberger was nominated and elected as a convention delegate. Furthermore, to draft the state’s constitution, he was made chairman of the committee on the judiciary – quite an honor for a young man who had immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 7 with his family from the Hungarian town of Hedrei, which today is known as Hendrichovce of the Slovak Republic.

Weinberger was a Democrat, and very much a believer in Progressive reforms that were sweeping the nation. Among these was the idea that if citizens were dissatisfied with an elected official, they could initiate a petition, and if a sufficient percentage of voters signed that petition, the elected official could be subjected to a recall election, in which a majority of voters could then decide the fate of the elected official one way or the other. We take such elections for granted today, but the idea was controversial back then – especially as it applied to the judiciary.

Taft was a great believer in the independence of the judiciary – foreshadowing the role he would play following his presidency as the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court., appointed by President Warren G. Harding. When President Taft saw that the proposed Arizona constitution enabled judges to be recalled, he cried “foul,” worrying that if judges had to worry about how their decisions would be received by the popular electorate, concerns about reelection might take precedence over administering justice.

So, after the proposed Arizona state constitution was submitted to Taft, he refused to approve it, demanding that the provision enabling the recall of judges be taken out of the constitution.

Arizonans complied with his demand, and he then signed the proclamation.

Once Arizona became a state, it had sovereignty. That meant that it was able to enact its own laws with or without the President’s approval. Very quickly, Governor Hunt and the Arizona Legislature, then controlled by Democrats, reenacted the provision enabling judicial recall.

The controversy was much ado about nothing. Notwithstanding President Taft’s fears, the procedure has been very rarely used.

Between the time of the state convention and the signing of the proclamation by President Taft, Weinberger and his wife, Blanche, moved to San Diego. He initially went into private law practice, during which time he served as a member of the San Diego Unified School District board for 21 years, and also was the founding president of the United Jewish Fund, which today is known as the Jewish Federation of San Diego County.

He served as a city attorney for the City of San Diego, later was appointed as a Superior Court Judge, and following his defeat for reelection, was appointed by President Harry S. Truman as a federal court judge.

The federal bankruptcy court downtown is named for the judge, as was the Benchley-Weinberger Elementary School in the San Carlos area, in which his name was paired with that of longtime San Diego Zookeeper Belle Benchley.

Weinberger, who lived to be a nonagenarian, stayed active as a senior judge almost to the end of his life, which came in 1974. One of the judicial duties he most welcomed was conducting naturalization ceremonies for immigrants to the United States, telling the new Americans that even as he had been able to advance in his field, so too could they live the American dream.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com