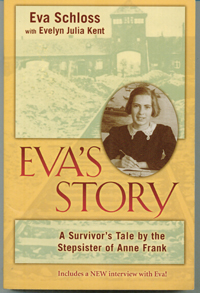

Eva’s Story by Eva Schloss (with Evelyn Julia Kent), William B. Eerdman Publishing Co, 2010, 226 pages.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—This is an updated version of the memoirs of Eva Schloss, who was the posthumous stepsister of the immortal Anne Frank. Originally published in 1988, the current edition brings readers up to date on the lives and deaths of the post-Holocaust family of Anne’s father, Otto Frank.

Eva and Anne were the same age, and in fact lived in the same block of buildings in Amsterdam, knowing each other slightly before they went into hiding with Dutch families. Like Anne, Eva was captured with her family by the Nazis, but unlike Anne, Eva survived the concentration camps. So did Eva’s mother, Fritzi, with whom she stayed together through the entire ordeal, despite the differences in their ages, selection processes at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and the chaos of liberation by the Russian Army.

Eva’s father, Erich Geiringer, and brother Heinz perished during a death march at the end of the war. Anne, her sister Margot, and mother Edith, died in the camps.

So many Holocaust memoirs have been written by survivors that unless this is the reader’s first, there will be few surprises in Schloss’s well-written, clearly understood narrative. She is perhaps a bit more candid than other survivors about her and her brother’s sexual yearning during the time they were in hiding, and about her sexual fears during the time she was in concentration camps. However, for the most part, the book deals with the routines of life under the Nazi reign of terror: the constant hunger, mindless work, lack of sanitation, brutality, and desperation.

So many Holocaust memoirs have been written by survivors that unless this is the reader’s first, there will be few surprises in Schloss’s well-written, clearly understood narrative. She is perhaps a bit more candid than other survivors about her and her brother’s sexual yearning during the time they were in hiding, and about her sexual fears during the time she was in concentration camps. However, for the most part, the book deals with the routines of life under the Nazi reign of terror: the constant hunger, mindless work, lack of sanitation, brutality, and desperation.

Whereas Anne was introspective in her famous attic, writing her impressions as they occurred, Eva in her recollections is far more reportorial. Her caution is intriguing. She treads very lightly on the issue of what it is like to be the sister of an icon. Although they knew each other, she and Anne were not friends. In their school girl days, Anne was more mature and sophisticated than Eva – one gets the feeling, between the lines, that Anne was a bit of an intellectual snob.

But this was not for Eva to say. Anne is revered throughout the world for her goodness and innocence; her diary has been translated into many languages; plays about her have been produced all over the world. As Anne’s story was bursting upon the world—after Otto read her diary—Eva was part of the lives that Otto and her own mother were rebuilding together. Later, Otto would become surrogate grandfather to Eva’s children, loving and cherishing his second family.

Eva indirectly disputes Anne’s famous verdict on the human condition. Anne was famous for writing that in spite of everything, she still believed that people were good at heart. Eva notes that Anne wrote that before she was sent to a concentration camp – and that she never had the chance to amend her diary. Had Anne, like Eva, lived through the privations of Birkenau – had she smelled the flesh of her fellow Jews belching out of the crematoria – perhaps she would have recanted her famous saying.

Accordingly, Eva describes her memoir as, in part, covering that part of the Holocaust that Anne could not write about. As you might imagine, Eva is far less convinced than Anne about the essential goodness of humanity. On the other hand, she does not discount the idea completely; she admits to also being an optimist.

Eva wrote the book knowing that history shall always record her as Anne’s sister, rather than vice versa. That the natural feelings of sibling rivalry were kept between the lines, to my mind, is to Eva’s credit.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World