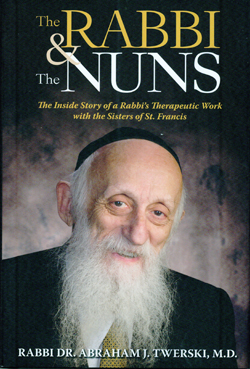

Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, M.D., The Rabbi and The Nuns, Mekor Press, 2013, ISBN 9781614651338. 190 pages.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO– Although the title sounds like the beginning of a joke, this book, in fact, contains numerous recollections of Rabbi Twerski’s career as the head of psychiatry at the Roman Catholic-operated St. Francis Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The anecdotes are written in bite-sized installments, so this is a book that one may interrupt and later pick up at any time without feeling a loss of continuity. I suspect that different insights in the book will appeal to different people, depending on what is going on in their lives or those of people about whom they care. So, reporting to you what I found particularly interesting may do justice to the book if your interests are similar, but, on the other hand, may lead you astray if you think my reportage is a complete synopsis. Let me say that Rabbi Twerski tackles numerous problems, not just those that I plan to relate.

SAN DIEGO– Although the title sounds like the beginning of a joke, this book, in fact, contains numerous recollections of Rabbi Twerski’s career as the head of psychiatry at the Roman Catholic-operated St. Francis Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The anecdotes are written in bite-sized installments, so this is a book that one may interrupt and later pick up at any time without feeling a loss of continuity. I suspect that different insights in the book will appeal to different people, depending on what is going on in their lives or those of people about whom they care. So, reporting to you what I found particularly interesting may do justice to the book if your interests are similar, but, on the other hand, may lead you astray if you think my reportage is a complete synopsis. Let me say that Rabbi Twerski tackles numerous problems, not just those that I plan to relate.

As a journalist, I often have the pleasure of dealing with older people–octogenarians, nonagenarians, even centenarians. I believe that there is much to be learned from the stories that they tell about events in their lives, even as I hope that someday younger people may find something of value in the stories that I tell about my life. Talking to people who have lived through history that I have only read about — or perhaps did not appreciate at the time, because the events occurred during my childhood– is particularly stimulating for me. The joy of listening to such stories comes with a very small price: the listener must also be willing to hear the complaints of the elderly, especially those who find themselves dependent on other people. For example, it is not unusual for older people–especially those living in “senior residences”–to complain that the attendants are not responsive to their needs, the room temperature is too cold, the food tastes terrible, the other residents are boring, and so forth.

I sometimes become impatient with such behavior. Why do they afflict themselves this way? From my viewpoint, the food isn’t really that bad, the room is not so cold, the attendants seem to be caring, and if the residents would take the time to get to know each other, hours and hours of enjoyable conversations in which they share their life stories might await.

In his book, Twerski relates the story of a nun who felt similar frustration. No matter how much she did for elderly patients, no matter how hard she tried, they always had a complaint.

The rabbi said such complaints may in fact be a coping mechanism, a way for the elderly patients to deal with the realization that the remaining period of their lives may be short, and that death is surely approaching. Complaining can be a way for the elderly to comfort themselves about the likelihood that they will be leaving this world sooner rather than later. It’s not such a wonderful world, after all, they can rationalize to themselves. What would I miss if I die? Rooms that are too cold? Miserable tasting food? Maybe when nature takes its course, it won’t be such a bad thing.

As often as I have been with elderly people–as many interviews as I have done with them–I never had thought that way about their complaining. So I was quite taken with Rabbi Twerski’s insight.

Turning to the opposite end of life–infancy–the combination rabbi, psychiatrist, and author told another story that got me to thinking.

He told of a child who was returning to the hospital for another vaccination. The infant didn’t understand what the vaccination was for, just that the big bad person had a needle that was going to hurt. So he cried and struggled and resisted as his mommy tried to get him to cooperate. Finally, the shot was given, the ordeal was done, and sobbing, the child held on tight to his mommy for comfort. He didn’t know why he had been subjected to such pain, but knew that his mommy cared for him and loved him. Even though mommy was part of his being hurt, she still was a source of comfort to him.

Twerski said just as the mother had far greater understanding than the infant for the necessity of such a medical procedure, so too does God have infinitely more understanding than humans about why calamities must befall the world. As the infant trusts in its mother, so too does the rabbi put his trust in God.

A significant segment of the book has to do with alcoholism, particularly among members of the clergy. If someone comes down with Parkinson’s Disease, or cancer, no one blames him. But if someone suffers from alcoholism or drug-dependency, this is seen as a moral failing, particularly among the clergy. However, Rabbi Twerski has a different viewpoint. He says that most of American society approves of the use of alcohol, even encourages it. Most social gatherings include alcoholic drinks as an option. Having a beer while watching a baseball or football game is commonplace, almost expected behavior. Various religious rituals include wine. However, some people, by virtue of their genetic make-up, are unable to regulate their consumption of alcohol, or even to be aware of the changes in their behavior that the alcohol is causing. This is not a moral failing, but rather it is a medical-psychological problem in Rabbi Twerski’s view. Society needs to be more compassionate. What the world needs is… rachmanis.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com