By Jerry Klinger

Herman Stern was a small-town North Dakota clothier based in Valley City. He was isolated, remote from any major Jewish community. He and his wife lived their lives modestly and with community respected dignity on the Dakota Plains.

Stern became a major, American Holocaust rescuer.

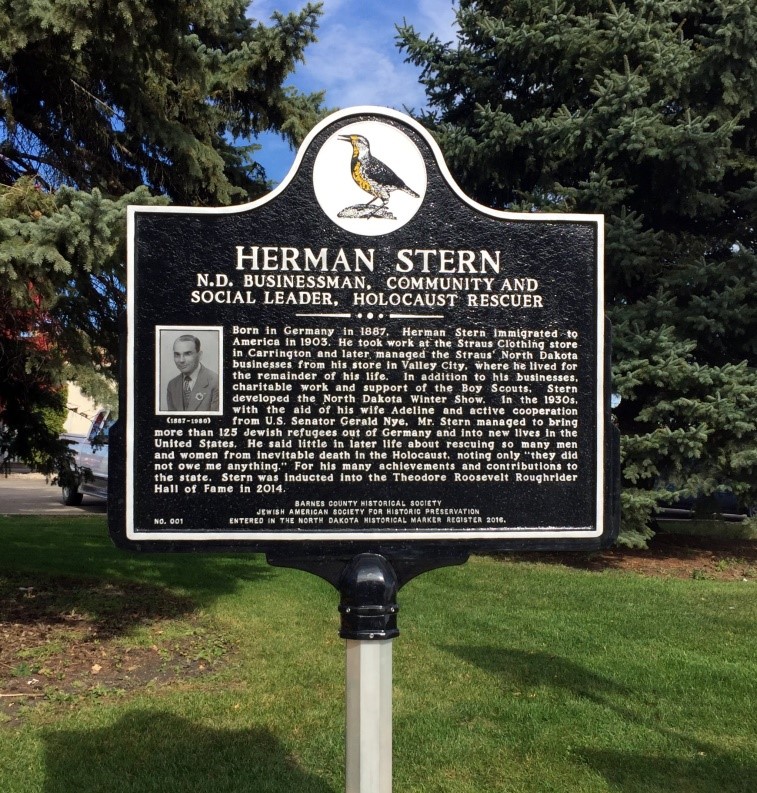

On Oct. 15, 2016, the State Historical Society of North Dakota erected the first historical roadside interpretive marker in the State’s history honoring Herman Stern. The marker project was sponsored by the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation with support from the Barnes County Historical Society and the community of Valley City.

Herman Stern, N.D. Businessman, community and asocial leaders, Holocaust Rescuer

Confronted with a choice, Stern, with assistance from his wife Adeline, chose to rescue when many others did not or would not.

Herman Stern was born in Oberbrechen, Germany in 1887. He immigrated to the United States when he was sixteen years old to work at his cousin’s, Maurice Straus, clothing store in Casselton, N.D. Four years after arriving in Casselton, Stern with demonstrated skill, adeptness, and a solid sense of business management, became the manager of the Casselton location. Straus opened a second store in Valley City. A few short years later, Stern became manager and eventually owner of what would grow to be a seven clothing store chain spread across North Dakota. Stern remained in Valley City for 70 years becoming an integral part of the social and economic life of the community.

As the dark clouds of the Holocaust gathered in Germany with the rise of Nazism life for Jews became increasingly difficult. The world calamity of the Great Depression exacerbated and gave excuse to the Nazis to institute increasing oppressive legislation specifically focused on getting rid of Germany’s Jews.

At first, many German Jews did not wish to believe the words written in Hitler’s manifesto, Mein Kampf, or believe the extremism of his words aimed at them. Germany had a long history of antisemitism but also culture, science and learning. Germany was only going through a phase, a transition that would return to toleration and acceptance, they told themselves.

The Jews of Germany and the world looked at developments in Germany affecting their brethren. They chose to deny the disease of antisemitism would become virulently life threatening.

The Nazification and dejudaization of Germany began by nurturing and capitalizing on centuries of Jew hatred. The Nazi goal was simple, to make Germany Judenrein – Jew free – force them to leave. Slowly at first and then with increasing desperation, German Jews began searching for somewhere that they could escape to. Jewish Palestine wanted Jews. Palestine as a safe haven was closed by the British who reneged on the promise of the Balfour Declaration. The British surrendered, as European Jewry’s darkest hours approached, to Arab oil blackmail and their own brand of antisemitism.

One avenue of escape was the Golden Land of America. But America as a safe haven was difficult to get to because of the U.S. State Department. America had closed its open door immigration policy years earlier adopting a quota system controlled by visas favorable to special racial groups, especially those from Northern Europe

The State Department put special obstacles, applied with extra rigor, to Jewish immigration. A visa applicant had to demonstrate they would not become an economic burden upon an America struggling with the Great Depression and high unemployment. Refugees leeching scant American resources and jobs from Americans were not wanted.

German Jewish refugees had to have sponsors in America who would guarantee they would not become welfare dependents. Even with a sponsorship, the State Department went to extreme lengths to make the process and the paperwork as byzantine as possible.

Herman Stern began receiving requests for help from his family in Germany. At first he could not believe what he heard about the deliberate destruction of Jewish life. Reluctantly at first, economic times were hard in North Dakota, Stern began to try and help bring his family to America. At every corner, the State Department threw up additional road blocks. They demanded proof of familial relationships, proof of economic support, proof of Stern’s financial resources and even demanding his tax returns.

Conditions worsened as obstacle, after obstacle was quietly and studiously surmounted by Stern only to have the State Department continue to drag its feet.

Stern turned for help to a non-Jewish friend in Washington, D.C., an America Firster, an isolationist, a North Dakotan who many today would cynically characterize as narrow minded and myopic, Senator Gerald Nye. Almost until the beginning of WWII, no matter how many times, Stern appealed to his friend, Nye never turned Stern down for help. Nye was a powerful and influential Senator in Washington. If Stern needed it, Nye went directly to the State Department for a “talk” as to how they could help expedite Stern’s visa requests.

In the beginning Stern helped only his family. Soon, family of family, friends of family and then desperate Jews who heard there was a man from the God only knows place of North Dakota, reached out to him.

Stern did not have to help the strangers. He was not a particularly rich man and the additional costs, demands, and requirements to obtain the visas of life became increasingly hard on him and his family. Stern did not say no. His conscience would not permit him to say no.

Stern eventually was able to rescue from Germany, over 125 souls from certain death.

Years later, Stern was asked if the rescued owed him anything. He modestly, yet powerfully responded, “they do not owe me a thing.”

When the economic pressures of rescue became too great for Stern, he tried to enlist help from Jewish communal organizations and charities. Stern realized he could rescue even more Jews by bringing them to North Dakota as “farmers.” Stern begged for help from Rabbi Stephen Wise the Jewish American leader who had Roosevelt’s ear. Wise turned Stern down for funding as did the others.

American Jewish organizations were busy fighting each other over how best to save Jews, not to intimidate President Roosevelt, nor raise anti-Semitism in America. American Jewish leadership remained timid as Jewish lives evaporated and even attacked those, such as the Bergson group, who challenged their timidity.

Rescue was a choice. Except for a very small handful of American Jews who acted individually to rescue, few American Jews reached beyond their immediate families. When World War II broke out, 200,000 American visas, that could have rescued Jewish lives, remained unissued.

Halachicaly, organized American Jewry faced a quandary. If rescuing Jews endangered the Jews who were already here, they did not have to rescue.

It was an irony, as explained by an Aish HaTorah Rabbi. Can Jews risk Jews to save Jews?

“According to Jewish Law, if the Jews in the town (besieged by Nazis) were being told to give up specific members of the Jewish population for death then they would be forbidden to do so. If they were being told that they have to give a up a certain percentage (to save the rest) they can do so but no one can be forced to be included in those who are being given up to the Nazis. However all of that is only applicable if it is the Jews who are being forced to make the decisions.”

Herman Stern began by rescuing his own. Soon, he was caught up, inevitably in his own decision. It was a slippery slope. While others bickered, Stern chose life.

Stern never talked much about his rescue efforts. He remained a modest pillar of the Valley City community devoting much of his later years in support of the American Boy Scouts, and Zionism.

March 2014, Herman Stern was recognized by North Dakota Governor Jack Dalryimple with the Theodore Roosevelt Rough Riders award and the honorary rank of Colonel. It was North Dakota’s highest honor.

Never a particularly religious or observant Jew, except at High Holidays when Stern would make the long drive to Fargo to attend schul, he lived his life the best way a Jew could.

He walked humbly before his God.

The text of the marker honoring Herman Stern reads as follows:

Herman Stern

N.D. Businessman, community and social leader, Holocaust Rescuer

Born in Germany in 1887, Herman Stern immigrated to America in 1903, where he took work at the Straus Clothing store in Carrington. Stern later managed the Straus’ North Dakota businesses from his store in Valley City, where he lived for the remainder of his life. In addition to his businesses, charitable work and support of the Boy Scouts, Stern developed the North Dakota Winter Show. In the 1930s, with the aid of his wife Adeline and active cooperation from U.S. Senator Gerald Nye, Mr. Stern managed to bring more than 125 Jewish refugees out of Germany and into new lives in the United States. He said little in later life about rescuing so many men and women from inevitable death in the Holocaust, noting only “they did not owe me anything.” For his many achievements and contributions to the state, Stern was inducted into the Roughrider Hall of Fame in 2014.

Barnes County Historical Society

Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation

North Dakota Historical Marker Register 2016

*

Jerry Klinger is president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. (www.JASHP.org) and may be reached via Jashp1@msn.com