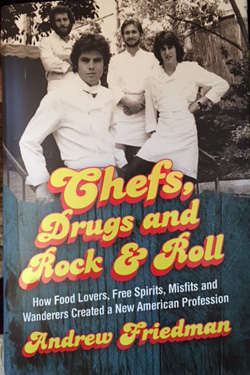

Andrew Friedman, Chefs, Drugs and Rock & Roll, How Food Lover, Free Spirits, Misfits and Wanderers Created a New American Profession, Ecco, $27.99, 464 pages

© Oliver B. Pollak

RICHMOND, California — Andrew Friedman gave a reading at San Francisco’s Omnivore Bookstore. After the talk I asked the author if the book has some Jewish content. He uttered excitedly, ”Oh yes, look at chapter 2, it’s all about Jews.” I emailed the publisher for a review copy which arrived a few days later at my front door. The 14-page Index, although not listing “Jew,” revealed that Jonathan Waxman had the largest entry, 9 lines, and was interviewed four times.

RICHMOND, California — Andrew Friedman gave a reading at San Francisco’s Omnivore Bookstore. After the talk I asked the author if the book has some Jewish content. He uttered excitedly, ”Oh yes, look at chapter 2, it’s all about Jews.” I emailed the publisher for a review copy which arrived a few days later at my front door. The 14-page Index, although not listing “Jew,” revealed that Jonathan Waxman had the largest entry, 9 lines, and was interviewed four times.

When the text and Index contains Abrams, Berkowitz, Bromberg, Feniger, Goldstein, Kafka, Katz, Lazaroff, Lieb, Mizrahi, Pritsker, Reichl, Rosenthal, Rosenzweig, Rothstein, Schulman, Sheraton, Siegal, Waxman, Weinstein, Wine, Wise, Wolfert, and others, you know there is a Jewish component. Another food writer said that in the culinary world even when their name does not look Jewish, they could still be Jewish, or have a Jewish spouse.

Friedman’s 215 interviews, accomplished between 2010 and 2017, cover the early 1970s to the emergence of the Food Network. He has been collaborating with chefs for about 20 years. He is a chef writer, not a food writer. The chefs did their magic in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco with some in Chicago, Santa Fe, and New Orleans.

Friedman is an epiphany hunter, asking when chefs get turned on to cooking, when they intellectualized and professionalized, and when they started innovating. Some of the interviews referred to events occurring half a century before. Wolfgang Puck observed, “everybody remembers history differently.” Chef egos have a tendency to push their personal creativity and contribution to the forefront.

Alice Waters, Jeremiah Tower, Waxman, and Wolfgang Puck established culinary benchmarks.

At the core was fresh, seasonal, local, and grown or raised by people you know, and a layering of a cult of personality. Chez Panisse in Berkeley celebrates 50 years in 2021. Some endeavors did not last a year. According to Thomas Keller of The French Laundry, “There’s no one reason that anything fails. It’s an accumulation of a lot of different things.”

The love affair with French cuisine merged into Nouvelle Cuisine, American cuisine, and New World cuisine. There’s a tension between apprenticeships in French kitchens, cooking schools in Paris, New York. and San Francisco, and trade schools. Chefs pore over cookery books, exercise their intuition and innovate. Ego, getting credit, the daily take, getting paid, ownership interests,and drinking after midnight fill their lives as well as fascinating details and intrigue between the front of the house, the kitchen (back of the house), and celebrity diners.

Satisfied dinner guests at a private home sometimes suggest, “You guys should open a restaurant.” In 1979 five New York couples opened restaurants. Three restaurants were short lived. Two of the men were lawyers. Two couples got divorced. In the same year Tim and Nina Zagat developed their own culinary advice empire which is now owned by Google,

Friedman reports, “The Five Couples were also… with the exception of a former actress who was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, it must be said, all Jewish, although it might be something else that set them off from other young cooks in town.” One interviewee stated, “I don’t really think it’s about Jewish as much as I think it’s about class,” “There was the money and the sophistication to be comfortable in the dining room, to appreciate sitting in the dining room as an aesthetic experience; some people were cooks and some people were into the restaurant business.” On the business side one of the five couples contemplated replacing the tipping pool with a service charge.

Perhaps a nurturing Jewish mother or grandmother, a steady diet of home cooking, with mouthwatering noodle kugel, matzo ball soup, and recipes drawn from cookbooks, newspapers and magazines, may have influenced some young men and women toward professional culinary pursuits.

A May 1983 banquet at Stanford Court Hotel on San Francisco’s Nob Hill honored New Orleans chef Paul Prudhomme, who had introduced the “signature dish” of blackened Red fish in 1980. Twelve chefs from around the country prepared the resplendent Menu and the after party. The extravaganza marked a turning point in American cuisine, similar to California wine achieving world class status, by French standards, in the early 1970s.

The cavalcade ends in the early 1990s with the arrival of Thomas Keller, Charlie Trotter, and Emeril Lagasse, and others. The molecular and fusion movement were in the air. West coast women were taking charge of the front of the house and the kitchen. Nonsmoking, no reservations, and a national camaraderie of celebrity chefs playing food together was nascent.

Friedman comments at least ten times that the period he covers had no internet, in contrast to current communications and research conditions. He published Knives at Dawn: America’s Quest for Culinary Glory at the Bocuse d’Or, the World’s most Prestigious Cooking Competition in 2009, and has a podcast, Andrew Talks to Chefs.

.

Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, is a freelance writer now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com