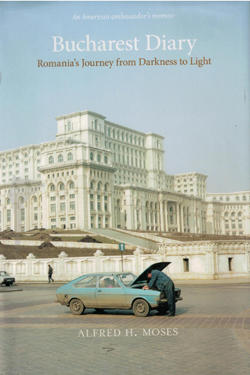

Bucharest Diary: Romania’s Journey from Darkness to Light by Alfred H. Moses; Brookings Institution Press © 2018; ISBN 9780815-732723; 394 pages including index and glossary of people and places.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Formerly national president of the American Jewish Committee, trial attorney Alfred H. Moses had successfully lobbied the Communist government of Romania to permit Jews to emigrate to Israel—an achievement that later recommended him to be appointed ambassador to Romania by U.S. President Bill Clinton. Moses’s ambassadorial service in Bucharest came after the Communist government of Nicolas Ceaşescu had fallen, and the democratically elected governments of successive Presidents Ilon Iliescu and Emil Constantinescu were struggling to win Western acceptance and membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

SAN DIEGO – Formerly national president of the American Jewish Committee, trial attorney Alfred H. Moses had successfully lobbied the Communist government of Romania to permit Jews to emigrate to Israel—an achievement that later recommended him to be appointed ambassador to Romania by U.S. President Bill Clinton. Moses’s ambassadorial service in Bucharest came after the Communist government of Nicolas Ceaşescu had fallen, and the democratically elected governments of successive Presidents Ilon Iliescu and Emil Constantinescu were struggling to win Western acceptance and membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

To win its place among Western allies, Romania needed to privatize many of its state-run businesses, and to negotiate treaties of friendship with neighbors Hungary and Ukraine, which had long-running disputes with Romania over territories that had been grabbed first by the German Nazis and later by the Russian Communists.. There was resistance to both of these requirements from various factions in Romania. Politicians were reluctant to privatize industries if that meant throwing people out of jobs, however unnecessary those jobs might be. Various ethnic groups in Romania resented both Hungary and the Ukraine, making tenuous the continued existence of two presidents’ parliamentary coalitions.

Besides gently shepherding Romania through such difficult decisions, Moses also needed to negotiate the mine fields of Romania’s internal politics. Several parties vied for influence and American favor, and Moses, a successful lawyer but not a career diplomat, needed to tread very gently. In his book, he admits some occasional missteps.

This memoir was written in diary form; that is, events are presented chronologically rather than thematically. So, for readers to learn how the two treaties finally were negotiated, they must work their way through the entire book rather than read a chapter devoted strictly to that phase of Moses’s work. I’d have preferred that Moses presented his work subject by subject. One fascinating chapter could have been called “An American Jew in Romania” because Moses, a fairly strict Sabbath observer, made a practice of visiting active and former synagogues wherever in Romania he traveled. With the Clinton Administration’s approval, he also worked for the restoration of Jewish properties seized both by the Nazis and the Communists.

In his diary, there also are entries about places he ate, people he met, diplomatic occasions he attended, and the considerations that go into state visits – whether those be of a Romanian president going to the United States, or an American president coming to Romania.

I would say that this book will appeal mainly to two categories of readers: First, to people of Romanian nationality or descent, both Jewish and Christian, especially because Moses makes some savvy observations about Romania’s leaders. Second, to people who are considering applying for a career in the U.S. State Department. The book provides a fairly comprehensive look at the duties of an Ambassador as well as the interplay among the host country, the ambassador, envoys from other nations, and such various components of the United States as the President, Congress, and U.S. business interests.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com