I alighted from my pony, and gave him the range of his lariat. I perceived that he preferred a breakfast of fresh grass to the contemplation of the sublime scene around me, to which he seemed totally indifferent. — Solomon Nunes Carvalho, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West with Col. Fremont’s Last Expedition.

By Susan C. Ingram

Baltimore Jewish Times

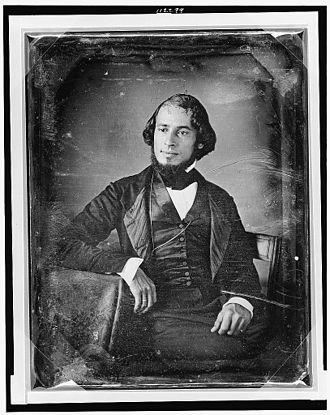

BALTIMORE, Maryland –The sublime scene surrounding Baltimore daguerreotypist Solomon Carvalho that September day in 1853 was the sunrise-lit expanse of prairie near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers, where Col. John C. Fremont and his party of 22 men, mules and supplies bivouacked before embarking on Fremont’s fifth expedition to map a suitable transcontinental railroad route through the Rocky Mountains.

Carvalho had been hired to record the expedition on daguerreotypes, an early photographic process that rendered mirror images of subjects onto silver-coated copper plates. Along the expedition he learned to ride horses and shoot a gun, he hunted buffalo and he came to admire and respect the Native Americans he photographed.

“Jewish pioneer” isn’t a phrase used often in the American lexicon, especially when talking about the Old West. But it is certainly an apt description of Carvalho, a Sephardic Jew and Baltimore resident who was a pioneer in many senses — in art, business, technology and religious life.

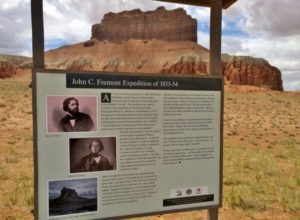

In recognition of that pioneering spirit and his unique place in the history of Westward expansion, efforts have been made in recent years to rekindle interest in Carvalho’s life, including a book and film. And Maryland native Jerry Klinger and Utah native Wade Allinson are collaborating on historical markers about Carvalho along Fremont’s expedition trail, including at Wild Horse Butte and Parowan, Utah, where the team escaped the mountains in 1854, suffering from scurvy, exposure and starvation.

“I do quite a bit of research about Jews on the American frontier, and it mainly goes to fight the negative stereotypes that Jews weren’t part of the American experience from the beginning,” said Klinger, president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation.

“To find Jews that were pioneers, to find Jews that were wagon masters, even gunfighters. The amazing part about the American experience is that it offered us opportunities to be whatever we could be. And the frontier, in particular, didn’t ask what religion you were. It asked what you could do, what could you bring to the table.”

From opening a daguerreotype studio and a synagogue in Baltimore to traveling the uncharted West with Fremont, Carvalho lived an exceptional life for a Jew of his time.

“Over and over, we see the new technology, whether it’s photography or the opening up of the West, and here was a guy who jumps to be part of these innovations. And that tells you something about his mind,” said Jonathan D. Sarna, Brandeis University American Jewish history professor, in the 2015 documentary Carvalho’s Journey.

Carvalho was born in 1815 in Charleston, South Carolina, into a Sephardic family that was prominent in the coastal city’s Jewish community. His father, a leader in the Reform Society of Israelites in Charleston, was an innovator in Jewish worship, introducing modernizations to traditional services, including adding English hymns.

The family moved to Baltimore in 1828, to Philadelphia in 1834 and to Barbados in 1842, during which time the young Carvalho studied fine arts and perfected his painting skills. Back in Philadelphia in 1845, where he married, Carvalho began experimenting with a new technology — daguerreotype.

In 1849, he opened a daguerreotype studio in Baltimore at 205 Baltimore Street and later opened studios in Charleston and New York.

“Solomon was part of a technology bubble in Baltimore in the 1850s that is somewhat analogous to what happened in Silicon Valley in the 1970s,” said Marvin Pinkert, executive director of the Jewish Museum of Maryland, which houses a Carvalho collection. “Trains, telegraphs and photography were fundamentally changing American life and Baltimore was the hub for all three.”

According to Elizabeth Kessin Berman in Solomon Nunes Carvalho: Painter, Photographer and Prophet in Nineteenth Century America, a 1989 exhibit catalog by The Jewish Historical Society of Maryland, “Carvalho immersed himself in the development of photographic technology, creating improvements which could aid and further refine the photographic process.”

Baltimore photographic historian, collector and researcher Ross J. Kelbaugh called Carvalho “an innovator,” who did hand-tinting of daguerreotypes in his studio.

“During that period he was active, there were approximately 23 daguerrean galleries in Baltimore,” Kelbaugh said.

Daguerreotypes required a complicated process of sensitizing a silver-coated copper plate with chemicals, inserting the plate into the camera and exposing it for a few seconds. The plate was then put into a heated chamber to create mercury vapors, which produced the exposed image. After the image was fixed in a chemical bath, washed with distilled water and dried, the plate was framed under glass as the surface was easily ruined if touched.

Carvalho, by his own admission, had taken the expedition job without much experience attempting this intricate process under the extreme conditions he would face working outside. “My professional friends were all of the opinion that the elements would be against my success,” he wrote in the opening pages of his expedition book, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West.

“To make daguerreotypes in the open air, in a temperature varying from freezing point to 30 degrees below zero, requires different manipulation from the processes by which pictures are made in a warm room,” he wrote. “Buffing and coating plates, and mercurializing them, on the summit of the Rocky Mountains, standing at times up to one’s middle in snow, with no covering above save the arched vault of heaven, seemed to our city friends one of the impossibilities.”

Kelbaugh expressed amazement at Carvalho’s ability to produce 300 daguerreotypes while, as he himself wrote, “suffering from frozen feet and hands, without food for 24 hours, traveling on foot over mountains of snow.”

“It was an incredible feat,” Kelbaugh said. “To haul all that equipment, to have all those plates and preparing the plates and exposing them and then developing the plates with all the things he couldn’t depend on — temperature, humidity — it was quite a feat and would explain, in part, why he was exhausted when he got back from it all.”

The only Baltimore daguerreotype by Carvalho that Kelbaugh knows of is a hand-tinted daguerreotype of a little girl that he said the Maryland Historical Society acquired serendipitously among a cache of Civil War artifacts a few years ago.

“It was an extraordinary example of his work,” Kelbaugh said.

When Fremont, in February 1854, decided the expedition and men were in serious danger (one man died on the trail), he ordered everyone to lighten their loads for a dash out of the mountains to Parowan, Utah. Carvalho buried his daguerreotype equipment, but saved the 300 daguerreotype plates. After recuperating in the Mormon settlement, he went north to Salt Lake City, where he spent time with Mormon leader Brigham Young before heading to California and a ship home.

Later, Fremont, who finished the expedition in California, did not allow Carvalho to use the daguerreotypes in his book, as Fremont planned an expedition book himself. Since daguerreotypes were not reproducible, many of Carvalho’s daguerreotypes from the expedition were redrawn by other artists and etchings of them were mass produced. Fremont then stored the daguerreotypes, and they are believed to have been destroyed in a fire decades later.

Kelbaugh speculates that the loss of Carvalho’s original daguerreotypes delayed appreciation of the West and the first forays into conservation.

“It could have made a dramatic difference in earlier appreciation of the wonders of the West, because this could have been the first major photographic documentation of the West,” Kelbaugh said. “Later photographers’ work would cause Congress to be inspired to create national parks. So, perhaps if they had survived, that might have motivated the desire for preservation of the wilderness and the viewshed.”

Sarna agrees.

“The great tragedy is that he took all of these daguerreotypes, which were lost,” Sarna said. “Had those daguerreotypes not burned in a warehouse, his reputation would be different and maybe be known to more people”

When Carvalho returned to Baltimore with his family in 1856, he and his wife started a synagogue in the spirit of what his father and other Jewish leaders in Charleston had done, incorporating modern ideas with traditional Judaism, including English hymns, prayer books and services.

“The Beit Israel Synagogue survived for only three or four years, from about 1856 to 1859. While Solomon was a founder, his wife Sarah Solis Carvalho was probably more influential in synagogue life,” Pinkert said. “She was the founder and president of the Baltimore Hebrew Sunday School Association — Baltimore’s first Sunday school and the first institution in the city, as I understand it, to have women teach the Hebrew bible.”

Carvalho was a follower of American Jewish scholar Isaac Leeser, who was influential in American Judaism.

“On the one hand, he’s a guy involved in the latest innovations in photography, and on the other hand, he is a supporter of [Jewish] tradition with a modern bent,” Sarna said. “And Leeser is exactly the person who he looks up to in terms of leaders of American Judaism at that time.”

The scope of Carvalho’s talent is far-reaching, from his well-known and respected work as a painter and portraitist, to his daguerreotype and later tintype work, to his best-selling expedition narrative, to patenting an apparatus for super-heating steam after failing eyesight forced him to give up painting and photography. He died in New York in 1897.

While Carvalho: Portrait of a Forgotten American by Joan Sturhahn was published in 1976, there are more recent efforts to remember him.

In 2000, New Mexico daguerreotypist Robert Shlaer published the book Sights Once Seen: Daguerreotyping Fremont’s Last Expedition Through the Rockies.

In 2015, filmmaker Steve Rivo followed Shlaer to the site of one of Carvalho’s images as part of the feature-length documentary Carvalho’s Journey, which includes interviews with Western and Jewish historians.

At the historical marker at Wild Horse Butte, Utah, the sight of another of Carvalho’s iconic images, the marker text recounts the hardship and danger Carvalho endured as he worked.

“The men of the expedition were bundled in winter coats and wrapped in tattered blankets moving ahead through the snow and ice,” the marker reads. “Many of the men were suffering from frostbite and the lack of food. The horses and mules were walking skeletons, and so were the men. Many of the men were without animals to ride and were forced to walk on frozen feet.

“Under these conditions, the men of the expedition found themselves at this location, now known as Wild Horse Butte. Despite the cold, snow and freezing temperatures, Carvalho took a daguerreotype picture of this geological feature. The expedition then traveled into Cathedral Valley and on to Thousand Lake Mountain. A few days later, one member, Oliver Fuller, died of exposure.”

Wade Allinson, who found Klinger through the Western States Jewish History Quarterly, is a descendant of the Mormons who founded Parowan, Utah, where Fremont’s party was nursed back to health.

“When I started looking into Carvalho, I saw what an amazing thing this guy did. The track that he made in 1854 with Fremont went through the county I live in,” Allinson said. “The writing that he left behind is really the only record we have of it. Because when John Fremont came through here, he wouldn’t let any of the people with him keep diaries.”

Carvalho skirted this rule by sending long letters home to his wife, which served as the basis of his expedition book.

When Klinger and Allinson attended the Wild Horse Butte marker dedication, they discussed a second marker recognizing Carvalho in Parowan. That marker is under development now and the two hope, after approval from city authorities, that the marker will be in place later this year.

Meanwhile, Klinger is making requests to the National Park Service, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and local Wayne County, Utah, authorities to name a grouping of rock obelisks in Capital Reef Park after Carvalho. Susan Fritzke, superintendent of Capital Reef National Park, said educational materials about the obelisks now include information about Carvalho.

Back in Baltimore, while working on recent exhibits about Jews in Shanghai and Jews in space, Pinkert has been contemplating the lives of remarkable Jews like Carvalho.

“What has driven the Jewish people to the ends of the Earth and beyond? And why do the rest of us find this phenomenon so fascinating?” he said. “It really shouldn’t be surprising that the religion of a nomadic people, forged in the wilderness, should retain some wanderlust in its cultural DNA.”

“The world seems to have delivered an endless supply of madmen and bigots to ‘encourage’ our travel,” he added. “Yet what really inspires us about explorers and risk-takers like [astronaut] Judith Resnick or Harry Houdini or Solomon Carvalho is the way they overcame stereotypes about our people and demonstrated an exceptional courage that we all aspire to.”

*

Reprinted with permission from writer Susan C. Ingram and the Baltimore Jewish Times