Plaque honoring Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington in Virginia

By Jerry Klinger

WARRENTON, VIRGINIA –Julius Rosenwald was the organizational genius and President of Sears and Roebuck. Rosenwald felt, as a Jewish American, a deep personal commitment to humanitarian issues. After Sears went public in 1906, Rosenwald, now an immensely wealthy man, faced a dilemma.

Rosenwald said, “I can testify that it is nearly always easier to make $1,000,000 honestly than to dispose of it wisely.”

Yet he did dispose of his money wisely.

Rosenwald began funding special projects, especially YMCA’s for Black Americans. He recognized the particularly difficult circumstances that American Blacks were experiencing when he wrote in 1911,

“The horrors that are due to race prejudice come home to the Jew more forcefully than to others of the white race, on account of the centuries of persecution which they have suffered and still suffer.”

That same year, he was introduced to Booker T. Washington, the Black President of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Their relationship was tentative at first. Washington invited Rosenwald to Tuskegee to see what his vision for Black America was. The visit began a firm, life-long friendship and direction for Rosenwald’s incredible generosity – Black educational opportunity.

Rosenwald was practical, pragmatic, realistic. He did not believe in simply throwing money at the problem of Black education. Together, Washington and Rosenwald developed a plan, a program, a positive approach for Black America’s tomorrows.

Rosenwald agreed to become a Trustee of Tuskegee University in October 1911. It was a major coup for Washington. Washington wrote to former President Theodore Roosevelt, who was also a trustee about Rosenwald.

“that Jew who gave so much money for colored YMCAs…I think he is one of the strongest men we have ever gotten on our board.”

At the beginning of their relationship, Rosenwald was the Jew, the other American, a Jew with lots of money. In the end, the relationship between the two men was not about money, it was mutuality, true friendship and respect.

Seven months after Rosenwald became a trustee of Tuskegee, Rosenwald, ever the practical man, needed to spell out in writing his motivation.

Rosenwald, once committed to something he believed in, went full forward. But he needed to define his reason for doing so to himself and to others who might ask why a Northern Jew was interested in helping Southern Blacks.

Buried deep within the personal papers of Julius Rosenwald, housed at the University of Chicago is Rosenwald’s statement of purpose. The personal statement is often overlooked because it does not fit with the P.C. perception of Jewish motivation. It is the why, Rosenwald, as a Jew, felt it so necessary to do what he did and why he would spend his enormous fortune doing it.

s

“This matter of civic duty looms larger than any one point of American Jewish life. It is the small cloud upon the horizon which portends danger for the future. I do not believe that economic, social, racial or cultural considerations will ever play a large role in American anti-Semitism. Social discrimination little interests the best Jews and is laughed at by the best non-Jews. But I take it, if the Jew fails in the discharge of his civic duty, he does not demonstrate to the nation that it acted wisely when it gave the Jew shelter and liberty and freedom. The Jew must be a pillar of civic well-being and moral capacity. He must be the one who in in every crisis will be right, militant for the right, the ethical, the spiritual, the best in national life. If he falls short of this standard, he will himself have brought into being the monster which will one day destroy him and unseat him from his position of safety in America… If distrust grows, nothing can save us. We can only save ourselves by creating a healthy atmosphere – both within our own group and on the outside – of trust and confidence in our integrity and our motives. It may not be an easy path to go; but it will be a path of safety and the assurance of safety to ourselves and to those who come after.

“The Jew need not be lost in America. He needs but demonstrate his usefulness in the highest sense of the term, and America will save him for himself.

“If the American Jew will be but true to his traditional powers for righteousness, if he be faithful to the best traditions of his past, and ready to do his best for this land of his adoption and nativity, he can play a big role in the ethicalization of public life in this country.”

Together, Washington and Rosenwald developed a goal of addressing the terrible shortcomings of Black education in the South. By public policy, construction for Black schools was deliberately underfunded. The two men decided to do something about the injustice.

Rosenwald continued after Washington’s premature and tragic death, creating the Rosenwald Fund in 1917. By the time the self-liquidating Rosenwald fund terminated in 1948, Rosenwald’s efforts led to the construction of over 5,300 schools for Black Americans in 14 Southern States. Scores and Scores of Black American artists, writers, educators, and societal leaders were provided with scholarships, stipends and vital support from the Rosenwald fund.

The years have passed and the memory of Rosenwald and his efforts are fading. They are not totally forgotten.

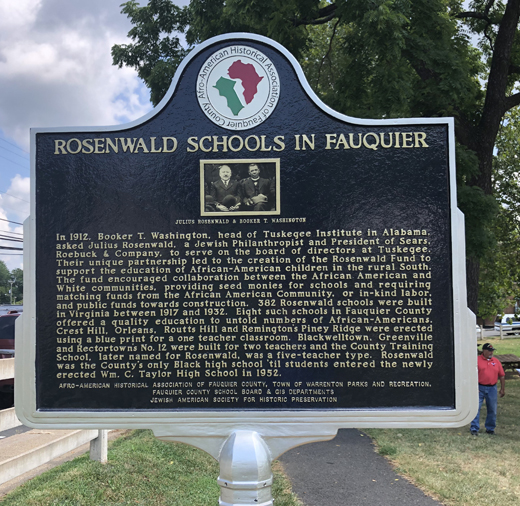

On August 3, the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation in partnership with the African American Historical Association of Fauquier County, Virginia, dedicated a historical marker to the Rosenwald schools of Fauquier. The dedication was attended by hundreds of whites and blacks together.

The marker is a silent sentinel of a past that gave hope and reality to a better future to thousands of Black American children in Fauquier. Located in Warrenton’s Eva Walker Memorial Park, the marker tells of the belief in a better future for decades to come.

The text of the marker reads:

In 1912, Booker T. Washington, head of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, asked Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish Philanthropist and President of Sears, Roebuck & Company, to serve on the board of directors at Tuskegee. Their unique partnership led to the creation of the Rosenwald Fund to support the education of African-American children in the rural South. The fund encouraged collaboration between the African American and White communities, providing seed monies for schools and requiring matching funds from the African American Community, or in-kind labor, and public funds towards construction. 382 Rosenwald schools were built in Virginia between 1917 and 1932. Eight such schools in Fauquier County offered a quality education to untold numbers of African-Americans. Crest Hill, Orleans, Routts Hill and Remington’s Piney Ridge were erected using a blue print for a one teacher classroom. Blackwelltown, Greenville and Rectortown’s No. 12 were built for two teachers and the County Training School, later named for Rosenwald, was a five-teacher type. Rosenwald was the County’s only Black high school ‘til students entered the newly erected Wm. C. Taylor High School in 1952.”

Rosenwald experienced a universal truth about giving. It overrode his historic, legitimate insecurity being a Jew. He knew anti-Semitism had a way of reappearing anywhere, even in America.

“All the other pleasures of life seem to wear out, but the pleasures of helping others in distress never does.” – Julius Rosenwald.

It is the best epitaph anyone can have.

*

Jerry Klinger is the President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. www.JASHP.org.