By Cantor Sheldon Foster Merel

ENCINITAS, California — The distinguished Rabbi Richard N. Levy paid tribute to his colleague, Cantor William Sharlin in recognition of 30 years as originator and Director of the Department of Music at the Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles.

“William, you taught me the difference between davening and singing, between listening to a chazzan praying, and singing along. You taught me that listening is also praying and there are times for congregational singing, and also listening. A chazzan like you is not a showman but is the essence of a shliach tzibur, (messenger of the congregation). William, you don’t talk much about God, but your song abides in the heights. Your aesthetics, your social conscience, permitted you to turn your chazanut soul where the shtetl would recognize its kinship with your music and Philosophy.”

In a new book, Cantor William Sharlin: Musical Revolutionary of Reform Judaism, author Jonathan Friedmann has captured the metamorphosis and transformation of Cantor William Sharlin (1920-2012), a most innovative cantor, synagogue composer, scholar, teacher and lecturer in 20th century Jewish music. Many of his compositions have been published and performed throughout North America.

Friedmann spent over ten years studying voice and Jewish music with Cantor Sharlin. And then began to write his biography. He organized Sharlin’s writings, music manuscripts, and interviewed him to preserve memories of his wide-ranging achievements His fascinating biography is filled with profound insights of Jewish liturgy, texts, pulpit -demeanor, and congregational singing.

These are a just few question Sharlin asks of his readers:

1. Does instrument accompaniment support or distract from the worship experience?

2. .Do congregations engage in mindless repetition of simple and well-known melodies?

3. Do congregations avoid melodies that require longer exposure to learn?

4. Does the split pulpit of cantor –rabbi present a danger of fragmentation rather than a unified atmosphere?

5. What would change if the Reform cantor turned around and only sang facing the Ark?

Sharlin was like a Fiddler on the Roof, standing with one foot in Jewish tradition he knew so well, and the other foot in modern classics, Jewish folk songs, and Broadway show music. His compositions reflect his ingrained Orthodox upbringing mingled with modernity, and is (as Friedmann described) subtle, complex, and even playful. .

Sharlin was raised in a strictly Orthodox Jewish family in New York and attended Yeshivas in both New York and Israel. In his teen years he became both fond and critical of his religious upbringing, and during army service in WW 2, he entered the secular world . With the help of the G.I. Bill of Rights, Sharlin earned a Master’s Degree in the musical classics, composition, and advanced piano from Manhattan School of Music in 1949.

He then considered becoming a Music Director for a congregation, and audited courses at the brand new cantorial school (first in America) at the Hebrew Union College in New York City.

It was immediately evident to the faculty that William’s musical education and background in Hebrew and Jewish music qualified him to be in 1951’s first class to graduate in the school’s history. After graduation, he was among founders of the American Conference of Cantors. and Bill (as he was called until his later adult years) and I became close friends. We traveled around New York City to hear the leading chazzanim (cantors,) and Bill was my guide and teacher.

A few years prior to entering HUC, he wrote a delightful musical setting for the Talmudic text, Ey-lu D’varim. His melody imitated the study mode of Talmudic students repeating phrases like a mantra, and William turned it into an art song. He accompanied me at the piano when I first performed it. Ey-lu Dvarim became a regular part of my concert repertoire for many years, and was recorded live in concert for my first CD, Standing Ovation. To my knowledge it was never published.

Although enrolled at cantorial school, William never thought of him self as a singer. When he sang at student chapels, however we all complimented his fine natural baritone voice and chazzanut (cantorial art).

Approaching his graduation, I urged him to consider taking a cantorial pulpit. Instead, he accepted the invitation from Professor Eric Werner to pursue a Doctorate of Jewish Music at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. William spent the next two years studying with Professor Werner, and also conducted the rabbinic students’ choir.

In 1952, when my late wife Marcie and I were planning our marriage we wanted William to be involved in the ceremony. Rather than chant as cantor he was more comfortable playing the organ. Our close friendship continued throughout the lives of William and his wife, Jacquie, a concert pianist of note.

The many compliments William received singing at cantorial school evidently sparked him to delve into books on the art of singing. An inborn scholar and musician, he actually taught himself to sing, and later even taught voice. Strengthened with new confidence in his voice, he left Cincinnati, and accepted the position of cantor at Leo Baeck Temple in Los Angeles with Rabbi Leonard Behrman. He served there for forty years.

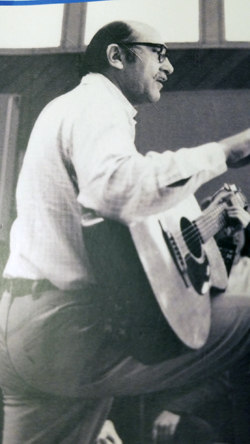

William quickly became a renowned cantor, offering innovative worship services and special music programs. He loved singing with organ and his devoted professional choir, but would just as soon hop off the pulpit with his guitar to lead or teach a new song.

Children in the religious school loved when the cantor came into their classrooms with his guitar to teach new songs. William also spent many summers doing the same at the NFTY (National Federation of Temple Youth) camps in Northern California, He never intended the guitar to replace the organ or to facilitate what he thought was superficial contact with the congregation, nor did he ever use the guitar during the Holy Days

William gave vocal lessons and coaching to many aspiring and active cantors. He was a demanding teacher, and expected professionalism of his students who respected his scholarship . He was among the first to open doors for women to become cantors before any seminary would accept them.

After finishing reading this biography, I glanced through the Epilogue and Appendix and found even more gems about his experiences, insights, and philosophy. Here are just a few:

…He describes how he tried to teach Debbie Friedman, already a celebrity about Jewish music, but to no avail.

…He successively taught Torah cantillation by first humming and singing the trope signs to English words.

…Quoted Rav Kook, “The old must be renewed and the new sanctified.”

…He criticized cantors and rabbis who hide behind the guitar and forget they are in a holy place. He felt the guitar should be used only to warm up the congregation for singing. (I believe he would be disappointed how the guitar and rock Jewish songs are now synonymous in many temples).

Cantor William Sharlin: Musical Revolutionary of Reform Judaism is very well written, easy to read, and filled with many thought-provoking insights into liturgy, worship and philosophy. I heartily recommend it to cantors, rabbis, and lovers of Jewish music of any denomination.

Author, Jonathan L. Friedmann is a professor of Jewish music history at the Academy for Jewish Religion California, extraordinary professor of theology at North-West University (NWU), South Africa, and a research fellow at NWU in musical arts in South Africa: resources and applications. He is the author, editor, or compiler of 19 books on music and religion. One may visit his website at jonathanfriedmann.com.

Cantor William Sharlin: Musical Revolutionary of Reform Judaism is available for purchase on Amazon

*

Cantor Merel is cantor emeritus of Congregation Beth Israel of San Diego. He may be contacted via sheldon.merel@sdjewishworld.com

.