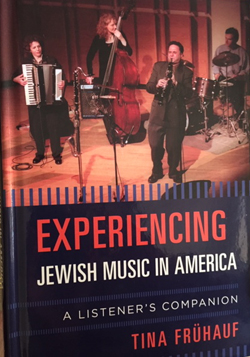

Experiencing Jewish Music in America: A Listener’s Companion by Tina Frühauf; Rowman and Littlefield

SAN DIEGO — As I read this comprehensive, engaging book about Jewish Music in America, I kept thinking about the extensive music collection we have in our Astor Judaica Library of the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center and what a wonderful course we could develop, using this volume as the textbook and our library’s lp records, CDs and DVDs for illustrations. We have most of the music Frühauf writes about in her book.

SAN DIEGO — As I read this comprehensive, engaging book about Jewish Music in America, I kept thinking about the extensive music collection we have in our Astor Judaica Library of the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center and what a wonderful course we could develop, using this volume as the textbook and our library’s lp records, CDs and DVDs for illustrations. We have most of the music Frühauf writes about in her book.

I also wondered how the author, born and educated in Essen, Germany, became so immersed in the study of Jewish music. When I posed the question in an email, she responded, “I grew up in a multi-denominational household and was exposed from an early age on to different notions of religious expression. …My early work in the field of Jewish music centered on a tradition lost on German soil, the decorous religious service of the 19th century. In my current work, I am looking closely at Jewish musical traditions that I partly experienced myself. My formal studies in Hebrew, liturgy, etc. only started when I entered university. Many German universities offer Jewish studies as a major or minor and students of all stripes attend such programs.”

The Folkwang Universität der Künste, Essen, Germany, where Frühauf earned her doctorate, is known for its outstanding faculty and alumni. The late Polish composer, Krysztof Penderecki and the famous French cellist, Paul Tortelier taught there. Pina Bausch, the German avante garde choreographer was an alumnus.

Tina Frühauf begins her book with Sounds of the Synagogue.

In this chapter, she gives historical background about the Sephardic Jews who first settled New Amsterdam, the Ashkenazi Jews who followed, and the types of synagogue music they used. Much of the chapter, however, is devoted to examples by the great Ukrainian-born cantor, Joseph (Yossele) Rosenblatt and the song leader, Debbie Friedman.

The next chapter is Seasoned With Song, At Home and at the Jewish Table. Here, she goes into great detail about the song, “Shalom Aleichem,” sung on Shabbat, the Hassidic nigunim and the traditional songs sung for Pesach and Chanukah.

The third chapter gives a wonderful overview of the Yiddish Stage on New York’s Second Avenue, discussing the roles of great Yiddish operetta writers like Abraham Goldfaden, and famous actors like Boris Thomashevsky. She covers the next generation of composers and tells the history of Shelomo Secunda’s song, “Bei mir bistu shein,” which eventually became popular in an English version sung by the Andrew Sisters. She includes the reemergence of Yiddish Theater in the 21st Century by the Folksbiene of NYC, describing their 2015 production of Di goldene kale.

The fourth chapter is On The Silver Screen, and is devoted to Jewish music in Hollywood films, from Al Jolson’s portrayal in The Jazz Singer to the score of Schindler’s List.

The fifth chapter, Fiddling On Broadway, is mainly about Harnick and Stein’s Fiddler on the Roof, while the sixth chapter, On the Concert Stage, is subtitled, Classical Music and the Jewish Experience. This chapter introduced Daniel Schlesinger (1799-1839), a Jewish pianist and composer from Hamburg, Germany, who immigrated to the United States in 1836 and helped bring European classical music to New York City, paving the way for Jews to emerge among the important performers, promoters and patrons of the arts.

Among the Jewish composers, she writes extensively about Ernest Bloch, giving an analysis of his Sacred Service, and covers Leonard Bernstein’s Jewish works, particularly his Jeremiah Symphony. As an instrumentalist, I was disappointed that she made no mention of the great Jewish violinists and pianists that dominated the concert stages in the 20th century, particularly violinists Jascha Heifetz, Mischa Elman, Nathan Milstein, Fritz Kreisler, David Oistrakh, Yehudi Menuhin, Isaac Stern and pianists Arthur Rubinstein, Vladimir Horowitz, Arthur Schnabel, Gary Grafman, Leon Fleischer, Vladimir Ashkenazy and many others. Some of the violinists were mentioned in the editor’s introduction, but none by the author herself.

Chapter 7, Jews Who Rock the Stages, is mostly about Matisyahu, the reggae-Lubavitch Hassidic music pop star, and Lipa Schmelezer, a product of the Skverer Hasidim.

Chapter 8 deals with Pubs and Clubs and covers some of the Hasidic alternative-rock girl bands such as Bulletproof Stockings and Hopewell. It also describes the club, the Knitting Factory, where musicians such as John Zorn, David Krakauer and Frank London explored new forms of Jewish music.

The final chapter, Beyond A Single Venue, Klezmer Everywhere, talks about the original Klezmer groups in the early part of the 20th century, those led by Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein. She then devotes many pages to the ensembles that revived klezmer music, beginning in the 1970s. Although she mentions groups on both coasts, she does not include the three San Diego groups which spearheaded the Klezmer revival in our city, Ron Robboy’s Big Jewish Band, Bob Zelickman and Debbie Davis’s Second Avenue Klezmer Ensemble and Yale Strom’s Hot Pstromi. However, in the index of Selected Reading, she praises Strom’s The Book of Klezmer: The History, the Music, the Folklore. She calls it “An entertaining and carefully documented study of klezmer from its origins in Renaissance Europe through its reemergence as a popular art form in the late twentieth century in the United States.”

In the last chapter, Frühauf writes about the role the great violinist, Itzhak Perlman played in popularizing klezmer music by joining klezmer groups such as the Andy Statman Orchestra, the Klezmer Conservatory Band, Brave Old World, and the Klezmatics for the recording and documentary, In the Fiddler’s House.

Fruhauf concludes that Jewish Music in America “continuously evolved and transformed. Like all music, it is a product of its time and creators.” She predicts, “it will grow out of its legacy or preserve it and will continue to flourish.”

Author Frühauf is on the faculty of Columbia University and also serves on the doctoral faculty of The Graduate Center, The City University of New York. Her research is centered on music and Jewish studies. She has received fellowships and grants from the Leo Baeck Intstitute and The Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture.

Other books she has written include The Organ and Its Music in German-Jewish Culture (Oxford University Press) and the forthcoming Transcending Dystopia: Music, Mobility, and the German Jewish Community, 1945-1989 (Oxford University Press).

Frühauf writes with scholarly precision, historical depth and musical understanding. This book is a valuable addition to the library of anyone interested in Jewish music in America.

*

Eileen Wingard is a retired violinist with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra and a freelance writer specializing in coverage of the arts.

article interesting. fyi – perhaps Debbie Friedman might have, and still is considered to be, much much more than a “song leader?” in the 1970’s that would have been a accurate description of the role she played on the Jewish musical scene. thoughts?

I would love to take this course. Maybe you could teach it. I would be there.

Eileen , thanks for the review of this amazing book and your article. I presume it’s a new release. Keep up the great work. Your scholarship and writing are assets to our community. Shanna Tova. Fine regards, Sheldon