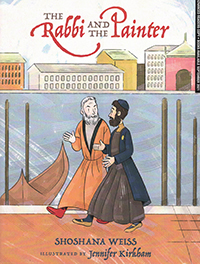

The Rabbi and the Painter; story by Shoshana Weiss; illustrations by Jennifer Kirkham; Kalaniot Books, 2021; ISBN 9780998-852782; 28 pages plus historical notes.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — This children’s book imagines a fictional friendship between the Mannerist painter Tintoretto and Rabbi Leon of Modena, whose most famous work, Historia de gli riti Hebraici, describing for non-Jews the rites and customs of the Jewish people, was written more than 40 years after Tintoretto’s death.

SAN DIEGO — This children’s book imagines a fictional friendship between the Mannerist painter Tintoretto and Rabbi Leon of Modena, whose most famous work, Historia de gli riti Hebraici, describing for non-Jews the rites and customs of the Jewish people, was written more than 40 years after Tintoretto’s death.

Author Shoshana Weiss imagines that the rabbi, also known as Judah Areyeh mi-Modena, was a boy when he first met Tintoretto on a bridge connecting the Ghetto to the rest of Venice, and that the two became friends. The time line is possible as Rabbi Leon of Modena lived from 1571 to 1648, while Tintoretto lived from 1518 to 1594.

Although the Christian painter was 53 years older than the future rabbi and author, Weiss suggests to her young readers that they could have built a friendship based upon their mutual boundless curiosity and willingness to explore worlds outside normal boundaries. Tintoretto, whose birthname was Jacopo Robusti, rejected the realistic style of painting of his day and became known by the nickname “Il Furioso” because of the energetic, emotional style of his paintings. Rabbi Leon, unlike some of his contemporaries, was unwilling to confine himself to the Jewish Ghetto, shut off from the outside world. Nor was he willing to limit his studies to traditional Jewish topics; he wanted to take in as much of the world as possible.

Weiss’s story culminates with Tintoretto consulting with a young Rabbi Leon to assure himself of some details appearing in his painting of The Last Supper, which hangs along with other of his paintings in the Church of San Giorgio Maggione. What detail he might have asked the rabbi about is left to our imagination, which is a weakness of this fable. Also, Weiss imagines that Rabbi Weiss “translated the story from the Hebrew for the painter.” However, the Christian Scriptures of Mark, Luke and John initially appeared not in Hebrew but in Greek, while scholars believe Matthew might have written either in Aramaic or Greek. So, the idea that the original language was Hebrew is a mistake that should be corrected in The Rabbi and the Painter’s next edition.

While Rabbi Leon bore the title of rabbi, he worked primarily as a cantor. In his own memoir, he admitted to the vice of excessive gambling. He also was a critic of Kabbalah as it was interpreted in the early 17th century.

Although the portrayal of Rabbi Leon is idealized, I nevertheless liked the story’s moral, which is if we are open-minded and willing to listen to people of different backgrounds, we can intellectually profit from the exercise by widening our own world views. Further, I’m delighted that author Weiss exposes 21st children to the medieval time period.

*

Donald H Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com