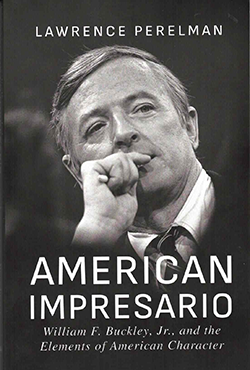

American Impresario: William F. Buckley and the Elements of American Character by Lawrence Perelman; New York: Bombardier Books, an imprint of Post Hill Press; © 2025; ISBN 9798888-453803; 216 pages plus appendices; $18.99.

SAN DIEGO – Author Lawrence Perelman is a classical pianist who realized that he was good, but not extraordinary. So, he spends his time now arranging concerts and other musical events for those artists whose talents exceed his own.

SAN DIEGO – Author Lawrence Perelman is a classical pianist who realized that he was good, but not extraordinary. So, he spends his time now arranging concerts and other musical events for those artists whose talents exceed his own.

In this memoir, or should I say “encomium,” Perelman announced that the late conservative columnist and commentator William F. Buckley Jr. was his hero. Perelman’s family had immigrated to the U.S. from the Soviet Union after the Soviets relaxed their restrictions on Jewish emigration. Perelman credited the change in Soviet policy to the pressure applied by U.S. President Ronald Reagan. Perelman also believed Buckley through his newspaper columns, books and “Firing Line” television program, was partially responsible for Reagan’s election.

Buckley was “an anti-Communist warrior, a fighter against anti-Semitism, defender of freedom, a Renaissance man, and the man credited with making Reagan a reality,” Perelman enthuses. “If not for this man and his philosophy, my family and people like us would never have made it to America.”

In 1994, as a teenager with a seemingly promising career as a pianist before him, Perelman wrote a letter of appreciation to Buckley, a classical music afficionado, offering to play for him in a private recital. Buckley responded affirmatively to Perelman’s offer. Knowing that Buckley had a particular fondness for Bach he “chose the C-Sharp minor Prelude and Fugue from Book I of the Well-Tenpered Clavier” as well as Debussy’s L’isle Joyeuse and Liszt’s Transcendental Etude No. 12, Chasse-neige, which Perelman described as a tremendously difficult piano piece.

The private recital was quite successful, with Buckley later sending Perelman a note saying “I was very pleased to meet you. You played beautifully, and you spoke with great maturity and wisdom. I wish you all the best, and please stay in touch.”

That encounter led to others over the next 14 years in which Perelman performed for his mentor Buckley’s guests at the columnist’s town house in New York City or at his home in Stamford, Connecticut. Another such recital was scheduled for the early evening of February 27, 2008, the day that Buckley died at the age of 82. Perelman had been Buckley’s overnight guest, rehearsing for the concert, so he was among the last persons who saw him alive.

For that unperformed recital, Perelman had devised a special program. Buckley had challenged him to learn Beethoven’s “Diabelli” Variations, which Perelman had played at another Buckley soiree the week before. The piece is formally titled “33 Variations on a Waltz by Anton Diabelli.”

Perelman described the work as “a monster of a piece,” paraphrasing conductor and pianist Hans von Bülow as saying “it is a microcosm of Beethoven’s entire output.”

Although this memoir is principally concerned with Perelman’s and Buckley’s love of classical music, Perelman also paid heartfelt tribute to Buckley’s vision that “those enslaved to Communism would be released from their chains.”

“He also resolved to unmask the creeping venom of anti-Semitism and to rid it from conservatism’s borders,” Perelman wrote. “What we lack today are more American impresarios of the Buckley mold, serving the interests of this nation and its greatest values rather than themselves. If we had more of them, our fight against anti-Semitism would be more successful and far more lasting.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.