By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — On November 7, 1918, Jewish Bavarian Independent Socialist leader Kurt Eisner, with the help of workers, peasants, and soldiers, seized power in Bavaria, becoming prime minister of the republic, formerly a kingdom. As a result of this revolution, the Bavarian throne was abolished along with the other monarchies of the German states, ending the House of Wittelsbach’s 738-year reign over Bavaria. Ludwig III fled to Hungary, Liechtenstein and then Switzerland.

The Jew Eisner overthrew the king. His government included Jews Ernst Toller, Erich Mühsam, and Gustav Landauer. In February 1919, Eisner was assassinated by a nationalist. On April 7, 1919, the Bavarian Socialist Republic was proclaimed, led by the leader of the Independent Social Democrats, the poet Ernst Toller, who resigned six days later, followed by the Bavarian Soviet Republic, led by the Jewish communist Eugen Leviné. Toller, a poet and dramatist, was a pacifist and was unable to lead the violent regime that was the Bavarian Soviet Republic.

Opposition leaflets described the situation in the Communist-held city as follows: “Many houses were burned down and large sums of money disappeared forever. Arrests were made indiscriminately. […] Munich was cut off from the rest of the world. The transportation of supplies stopped. The lives of infants, the sick and the weak were in grave danger. Coal became a rarity in the poor man’s kitchen. […] The revolutionary tribunal persecuted citizens for every free word against the shameful management of the foreign rabble. Hostages were brutally murdered.” The place of execution of radicalized nationalist hostages was the Luitpold Gymnasium. Banks were nationalized. The communists took apartments from the rich and gave them to the poor. “The “foreign rabble” was considered to be the Jews.

Leviné was not worried about starving children: “What would happen if there was less milk in Munich for a few weeks? In any case, most of it goes to the children of the bourgeoisie. We have no interest in their surviving. There is no harm if they die – they would have grown up to be enemies of the proletariat.” The newspapers called the leadership of the republic “a gang of lunatics, fantasists, fanatics and criminals” and “vain agitator outsiders.” The poet and writer Isolde Kurtz called the Communists a “terrorist group.” In early May 1919, the republic fell, Landauer was lynched, Leviné was convicted and shot. Toller was arrested and convicted of treason. Mühsam was arrested, convicted of treason, and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

The Bavarian Soviet Republic horrified the Germans. Thomas Mann was appalled by the possibility of the revolution’s victory: “We talked about whether the salvation of European culture was still possible […] or whether the Kirghizian idea of annihilation would win. We were also talking about the type of Russian Jew, the leader of the international movement, this explosive mixture of Jewish intellectual radicalism with Slavic Orthodox fanaticism. The world, which has not yet lost the instinct of self-preservation, must take action against this breed of people with all its strength and in a short time, according to the laws of wartime.”

The revolution of November 1918 in Berlin was perceived as German, and the Jews were blamed for the Bavarian Revolution. American historian Christopher Browning wrote in his book The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Politics (2004): “The Jew became a symbol of leftist politics, of exploitative capitalism, of various kinds of avant-garde experimentation in culture, of secularization – of everything that was rejected by a fairly broad conservative part of the political spectrum. The Jew became the perfect political irritant.”

Commerce Counselor (“commerce counselor” is an honorary title given to prominent businessmen) Sigmund Fränkel, leader of Munich’s orthodox Jewish community and one of the founders of Agudath Israel, was frightened by the active role of Jews in the revolution. His 28-year-old son Abraham Fränkel, a graduate of Munich’s Luitpold Gymnasium, the site of the execution of the hostages, described his father’s position in Memories of a Mathematician in Germany: “Sigmund Fränkel expected that Jewish participation in the radical leadership would lead to a disastrous impact on Bavarian Jewry.” On January 5, 1919, at the end of the Bavarian Republic, the National Socialist Workers’ Party was founded in the Sterneckerbroi beer hall in Munich.

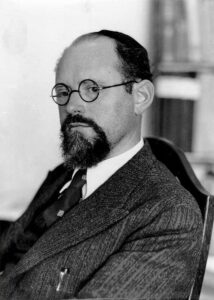

Abraham Fränkel (Adolf Abraham Halevi Fränkel) was born on February 17, 1891 in the family of a Munich Jew, wool merchant Sigmund Fränkel, where there were five children. He graduated from the city’s gymnasium in 1909. Fränkel studied mathematics at the universities of Munich, Berlin, Marburg and Breslau. In 1914 he graduated with honors and was drafted to the French front. In 1916, while on leave, he defended his doctoral thesis. In 1920 he was appointed a member of the board of trustees of the rabbinical college in Berlin. In 1922, Fränkel became a professor at the University of Marburg.

Worries over the revolutionary activities dangerous to Jews, condemned by his father, led Fränkel to Zionism. In 1926 he visited the future country of Israel for the first time. In 1928 he became a professor at the University of Kiel, but that same year, after consulting with Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, he accepted a professorship at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and in 1929 he repatriated. He received a leave of absence and returned to the University of Kiel, where he worked from 1932-1933.

On April 25, 1933, he was dismissed from Kiel University and moved permanently to the future Israel. He was a burning Zionist and a Hebrew fanatic. He was the first dean of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences and rector of the Hebrew University from 1938-1940. He taught in Jerusalem until his retirement in 1959, after which he taught at the religious Bar-Ilan University. In 1956, he was awarded the Israel Prize in the exact sciences. In 1960, he was elected to the Israeli National Academy of Sciences.

Fränkel is one of the authors of Cermelo- Fränkel‘s axiomatic set theory. His other works deal with algebra, the foundations of mathematics, the history of mathematics and the development of education in Israel.

Fränkel died on October 15, 1965.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education, and the author of 11 books.