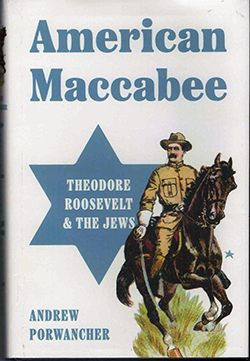

American Maccabee: Theodore Roosevelt & The Jews by Andrew Porwancher; Princeton University Press; © 2025; ISBN 9780691-271637; 287 pages of text plus 62 pages of appendices; $35. Publication date: June 10.

SAN DIEGO – Arizona State University history professor Andrew Porwancher has written a nuanced portrait of President Theodore Roosevelt’s relationships with Jews and his actions and/ or inactions in response to Jewish causes.

SAN DIEGO – Arizona State University history professor Andrew Porwancher has written a nuanced portrait of President Theodore Roosevelt’s relationships with Jews and his actions and/ or inactions in response to Jewish causes.

Even before he came to national office, Roosevelt had won plaudits as the New York City police commissioner who managed to upstage and convincingly counteract the lies of a well-known German antisemite, Harmann Ahlwardt, when the latter came to New York to raise money and spread calumnies about Jews and their worthiness. Roosevelt assigned 30 Jewish police officers to protect Ahlwardt, thereby making the hatemonger look ridiculous. If Jews were so contemptible, how come Ahlwardt owed his very safety to them?

At the midpoint of his second term, Roosevelt appointed Oscar Straus, a diplomat and attorney, as Secretary of Commerce and Labor – the first Jew in American history to serve in a President’s Cabinet.

Between these notable achievements, Roosevelt, as President from 1901 to 1909, wrestled with fashioning the correct American response to government-sponsored antisemitism in Romania and Russia. Both countries were under the autocratic rule of non-elected leaders, specifically a king and a czar. There was then, and still is today, a doctrine that no country should interfere in the domestic politics of another country, including what policies and restrictions such countries enact against any class of their citizens.

Pressed by Straus and financier Jacob Schiff to do something about Romania’s harsh antisemitic laws, Roosevelt and his administration struggled to develop an argument that U.S. interests were affected by Romania’s oppression of the Jews. It was decided to stress that those policies prompted Romanians Jews to immigrate to the United States causing a strain on the U.S. populace, particularly the Romanian Jewish community who had preceded them. But America of Roosevelt’s era prided itself on accepting the world’s “huddled masses, yearning to breathe free”—as advertised on the base of the Statue of Liberty — and the argument that immigrants were burdensome contradicted that conceit.

The King of Romania rejected the American note, and European commentators questioned why America – famous for its Monroe Doctrine rejecting any European interference in the Western hemisphere – should now hypocritically try to interfere in European affairs. Nevertheless, the effort endeared Roosevelt to a large portion of American Jewry.

Roosevelt learned from the Romanian experience. He faced the same diplomatic “interference” problem when pogroms erupted in Kishinev, and later throughout the Russian Empire. A public debate in the U.S., carried by newspapers, and in the halls of Congress, noisily weighed the pros and cons of Roosevelt sending a diplomatic letter to the czar. Russian diplomats, of course, followed the lengthy debate and tried to prevent such a protest being sent. The vigorous debate was monitored in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg, so Roosevelt’s protest was already known, although not through formal channels. When, at last, Roosevelt tried to convey his protest—which note the czar declined to receive—it was anticlimactic.

The U.S. had a definable interest in the scuffle with Russia over its refusal to treat American Jews with the same courtesy and rights as visiting American Christians. While the U.S. never noted on its passports what religion its citizens subscribed to, before Russia would issue visas, its agents cross-examined American citizens to determine whether or not they were Jewish. If they were Jewish, Russia refused to allow them to enter the country nor, in those rare instances where an exception was made, accord to Jewish Americans the same right to travel freely within Russia.

Roosevelt, meanwhile, was occupied with lending his good offices to peace negotiations between Russia and Japan, which had been at war over Russian occupation of Manchuria – a role for which he subsequently won the Nobel Peace Prize.

It was amid the peace negotiations that Russia promised to review its Passport Rules, which handed Roosevelt another Jewish “victory.” Subsequently, Russia did nothing substantive about the Passport Rules. It had made an empty promise.

The title of this biography is “American Maccabee,” which is a misconception. The Maccabees fought a life-or-death battle against their Syrian-Greek overlords, surprisingly winning a war in which they were outnumbered.

Roosevelt carefully chose his battles. He was far more cautious in his efforts to protect Jewish rights abroad. At one time, he even risked American Jewish frustration and displeasure by freezing efforts to influence the czar. At a time when Russia was in chaos, and the czar weak, Roosevelt thought such efforts might be counterproductive.

Nevertheless, Roosevelt stands out as a President who was a very good friend to the Jews. His memory is a blessing.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.