By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — Jewish Communists put forward the idea of a world socialist revolution. National revolutions did not sound large enough for them. National revolutions suited the indigenous nations. Jews needed supranational revolutions, which were easier to solidarize with.

Karl Marx, Alexander Parvus and Lev Trotsky were ideologists of a world permanent socialist revolution, i.e. a revolution that would take place like a chain reaction in different countries. Under the aegis of world revolution it was possible to disguise the Jewish energy directed by the oppressed nation against its oppression. If the revolution is permanent, with a constant increase in the number of participating nations, its accomplishment does not cast a shadow over the Jews who wish to liberate themselves in each individual country and pass off their local goals as international ones.

The active participation of Jews in the socialist movement was the result of their flight from an inconvenient nationality and the consequence of their assimilation into the universal non-Jewish world. Their break with national traditions turned them into radicals acting in the name of universalism and against a Jewry gravitating toward national values. According to Marxism-Leninism, Jews had to assimilate. Jewish leaders had to shake off their Jewishness and appear loyal to the international proletariat.

The subject of this essay is a Jew who left his Jewishness for the world socialist revolution. He did much for the power of the socialists in the USSR, for the economic prosperity of the country, but he poorly understood what system he was defending.

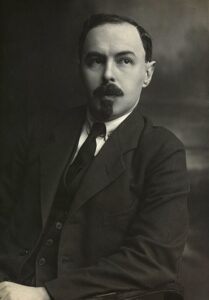

Hirsch (Gregory) Brilliant was born on August 15, 1888 into a wealthy Jewish family. His father owned a house in Moscow, on the first floor of which was located his pharmacy. His mother was from a family of wealthy merchants. The offspring of a wealthy family became fascinated by the ideas of taking wealth from the bourgeoisie, of which his parents were representatives. The offspring of a Jewish family was ashamed of the wealth of his family and the Jewish way of life. At the 5th Moscow Gymnasium, where he studied with the future poet Boris Pasternak, Nobel Prize winner in literature, and the future famous writer Ilya Ehrenburg, 15-year-old Gregory told his fellow students that he was a Marxist.

Gregory Brilliant entered the Law Faculty of Moscow University, but did not complete his studies due to his participation in the First Russian Revolution of 1905 as an activist of the RSDLP. In 1907, he was arrested at a meeting in Moscow’s Sokolniki neighborhood. In “honor” of this arrest, he chose the pseudonym Sokolnikov, thus preferring his Russian surname to the Jewish surname Brilliant. The court sent him into exile, from which he fled to France. In Paris, he entered the Sorbonne and wrote articles in the leftist European press due to his knowledge of six languages. At the Sorbonne he received his doctorate.

In April 1917, he returned to revolutionary Petrograd with Lenin, in a sealed train carriage. There he wrote articles against the Russian Provisional Government and voted in the Bolshevik Central Committee in favor of the armed overthrow of the Provisional Government. After the Bolsheviks came to power, he was given the task of nationalizing the banks, but in alliance with the old specialists he achieved the stability of the ruble. In February 1918 he led a Soviet delegation to the Brest negotiations and signed peace with Germany on behalf of the Soviet government on March 3.

During the Civil War, he led the 8th Army of the Bolsheviks. He had no military experience, but, as in financial affairs, he drew on the experience of military specialists of the tsarist army. He received the Order of the Red Banner for his military services. In 1920 he was sent to Turkestan to establish the Power of Soviets. His unit did not have enough weapons to fight the local insurgents. As in the other two cases, he succeeded not by force, but by intelligence: he freed from prison detainees from the local clergy, gaining their support for his measures. He abolished the draconian taxes imposed by his predecessors, replacing them with a moderate tax, and allowed free trade in the bazaars. Opponents of Soviet power were defeated.

Sokolnikov later led the measures of Soviet Russia’s new economic policy, under which small business and private initiative were allowed.

In 1922 Sokolnikov became head of the People’s Commissariat of Finance. After the Civil War, the ruble depreciated 50,000 times, prices for goods rose an average of 100,000 times. Sokolnikov hired specialists from the state apparatus of tsarist Russia and scholars of economics and finance. His team put into circulation a hard currency, the chervonets, equal to a ten-ruble gold coin of tsarist coinage, backed by 25% of its value in gold, other precious metals, foreign currency, and 75% in easily marketable goods. In 1925, the Soviet chervonets were officially quoted on the stock exchanges of many countries and were in circulation in Austria, Turkey, Italy, China, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Great Britain, Germany, Holland, Poland and the United States.

Under Sokolnikov’s leadership, state credit operations began to be carried out, short-term and long-term loans were issued. The People’s Commissariat of Finance gradually introduced a system of monetary taxes, state insurance and established savings banks. State and local budgets were separated, norms of Soviet budgetary law were developed, and financial discipline and accountability were introduced. Thanks to Sokolnikov, by 1925 the financial system was restored in the USSR.

In all his actions Sokolnikov relied on experts, was an opponent of harsh accelerated measures of industrial development, which led to inflation. He jealously guarded the national currency, repeating: “I am an adherent of the slow, gradual and careful realization of socialism in practice!” He was against printing money: “Emission is the opium of the national economy!” At the Bolshevik Party Congress in 1926, he was the only speaker demanding Stalin’s removal as General Secretary.

At the XV Congress in 1927, when Stalin outlined a course for the collectivization of agriculture, Sokolnikov opposed this policy, demanding “normal development of the economy, first in light industry.” According to his daughter Geliana Tartykova-Sokolnikova, “Father was very sharply opposed to collectivization. Sokolnikov believed that Russia is an agricultural country, and in no case should not ruin the village. This he wrote in 1925-1928.” He eventually lost his post as People’s Commissar of Finance.

In January 1934, Sokolnikov was sharply criticized for “mistakes in the field of industrialization.” Stalin’s “court Jew” Lazar Kaganovich declared from the rostrum: “A simple collective farmer is more politically literate than this ‘scientist’ Sokolnikov!” This was a criticism of an illiterate party official, uneducated and ignorant of economics. The Bolshevik mob hated Gregory Sokolnikov, an intelligent, educated, sensible and talented statesman.

In 1935, Sokolnikov was given the much smaller post of First Deputy People’s Commissar of the Forest Industry of the USSR. On July 26, 1936, Sokolnikov was arrested in the fabricated case of the “Parallel Anti-Soviet Trotskyist Center”, although he had separated from Trotsky back in the mid-1920s. To save his family, he confessed. Of the 17 convicted at this trial, 13 were shot. Sokolnikov, among the four convicted, received ten years in prison. However, Stalin did not forget his demand to dismiss him from the post of general secretary. At the end of May 1939, he was killed by NKVD agents. On December 16, 1988, Sokolnikov was posthumously rehabilitated.

Boris Bazhanov, Stalin’s former secretary who fled to the West, wrote in his memoirs: “I was often at Sokolnikov’s home. […] He […] was undoubtedly one of the most talented and brilliant Bolshevik leaders. Whatever role he was assigned, he handled it perfectly.”

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 11 books.