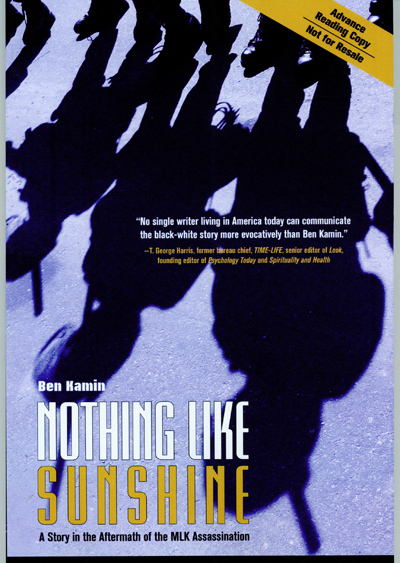

Ben Kamin, Nothing Like Sunshine, Michigan State University Press, 146 pages, $24.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—Rabbi Ben Kamin was in the tenth grade in Cincinnati, Ohio, on the April day in 1968 that Martin Luther King was assassinated while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. The murder of the Civil Rights leader had a profound effect on the high school sophomore, partly because King had inspired the future rabbi as no one had before, and partly because Kamin conflated the assassination with the apparent end of his friendship with Clifton Fleetwood, Jr.

Fleetwood was a black student who had served as drum major of the Woodward High School marching band. Kamin, white, was one of his drum beaters.

Fleetwood was a black student who had served as drum major of the Woodward High School marching band. Kamin, white, was one of his drum beaters.

Jews had been drum beaters in the early Civil Rights movement, helping to form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and lending legal support to challenge the constitutionality of laws that segregated or discriminated against African-Americans. Young northern Jews participated in Civil Rights demonstrations in the South, in some cases giving their lives for the cause. Notable rabbis, too, made common cause with African-Americans seeking their rights. Who can forget Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel—looking as if he just stepped out of the Bible—walking with Martin Luther King, whom Kamin identifies as a modern-day Moses.

However, the Jewish Moses got all the way to the mountain top; from Mount Nebo, he saw the Promised Land, and knew his people would achieve their objective of Canaan. King, in a famous speech the night before his murder, said he had been to the mountain top and had seen the promised land of freedom, but it was many years before his followers could sense his vision was becoming a reality.

When King was assassinated, grief, frustration and anger boiled over into the streets of cities across the United States—and that’s when Kamin and Fleetwood parted company.

Protesting the assassination, black students gathered outside the school for a march—and who knew what else, given the temper of the times—and Kamin was prepared to march with that band. But Fleetwood held up his hand, arresting Kamin, telling him that this demonstration was not for him. Kamin was heart-broken.

One might consider Kamin’s experience a metaphor for the overall relationship between African Americans and Jews. Seemingly, the friendship was solid between the two peoples. But then, African Americans apparently rejected the Jews. Some Jews, smarting over it, felt in their divorce that African Americans had turned against them. Perhaps it was because African-Americans felt a sympathy toward Palestinians, whom they identified as an oppressed people; perhaps it was because they felt that the Jewish community’s performance on the stage of Civil Rights did not match Jewish performance off-stage. Perhaps they needed to win their own liberation.

Whatever it was, it hurt.

Although Kamin saw Fleetwood from time to time in the hallways of the high school, there seemed an unbridgeable distance between them, that grew into a deep emotional chasm after graduation. Were it not for the turbulence surrounding King’s assassination, perhaps the disappearance of Fleetwood from his life would not have affected Kamin so profoundly; how many other classmates, white and black, have slipped back into the foggy recesses of his yearbook memories?

Over the years, Kamin obsessed over the question of what had happened to Fleetwood? Eventually, he began the quest that resulted in this book. The San Diego-based rabbi began looking for Fleetwood, not in Cincinnati, at least not at first, but at the former Lorraine Motel, which today is part of a Civil Rights museum. The book weaves Kamin’s personal reflections over the site and deed of the assassination with interviews of African-Americans about the impact of King’s murder on their lives.

Eventually, Kamin was able to find and speak with Fleetwood, and to get some of his questions answered about why they had drifted apart. The answer was a revelation; as well as he thought he knew his school friend, in that moment of separation, he had not known him at all.

As for the cryptic title of Kamin’s book, Nothing Like Sunshine, it was taken from a comment Fleetwood’s father made to Kamin after the King assassination. Kamin had telephoned the son, on the day of that demonstration, only to be told by the father that young Clifton had not arrived home yet. The news about King was terrible, horrible. And the father commented, “Nothing like sunshine.”

For many people the election of Barack Obama as President of the United States helped to dispel the darkness of racism that had blanketed the United States. Certainly this was true for Kamin, who rejoiced in the election of an African-American president as the realization of King’s dream. How sweet it was that in the same year, Kamin’s sleep need no longer be troubled over his shattered friendship with Fleetwood.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World.

Pingback: A bissel this, a bissel that …San Diego Jewish news and chatter | San Diego Jewish World