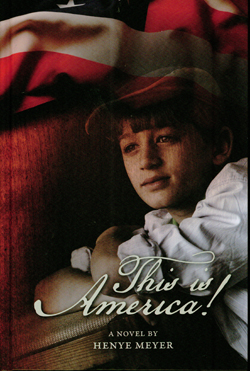

This Is America by Henye Meyer, Israel Bookshp Publications, 2012, ISBN 978-1-60091-196-5; 352 pages; price unlisted.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –In 76 episodes that previously had been serialized in the Orthodox daily newspaper Hamodia, this novel relates the experiences of members of a Ukrainian Jewish family who establish new lives as immigrants on New York’s Lower East Side in the early 20th century.

The narrator is Tcharna, a young marriageable woman who shares her mother Rifka’s desire to maintain a frum, shomer-Shabbas lifestyle in the United States notwithstanding the obstacles in the new country against doing so.

After hiding from pogromists, Tcharna’s father Tatte; older brother Elya; and younger brother Hershel preceded the women of the family to the United States, where they worked and saved enough money to send money for the women’s passage in steerage to New York City.

On their arrival, Rifka, Tcharna, and Bina-Gittel, 6, find that the males of their family had abandoned many of their observant ways. Tatte works as a presser and Elya as a cutter in a clothing factory, while Hershel has become part of a Jewish gang. Tatte explains that in his factory and most of the others, workers are required to work on Saturdays– or they will be fired.

Perhaps to assuage his guilt over abandoning the old ways, Tatte urges his wife and oldest daughter to do the same, but they resist. This results in a tense and divided household. Meanwhile the two younger children, under the influence of secular schools, swing back and forth, succumbing at times to peer pressure, at other times to Jewish mentors.

The struggle goes on against the backdrop of New York City in the first decades of the 20th Century, including the processing of immigrants at Ellis Island; the noise and crowds of the Lower East Side; sweltering tenements; the process of doing piece-work sewing at home; enduring foul conditions in sweat shots; labor unrest; the horror of the Triangle Shirt Waist Factory fire; children serving as English interpreters for their parents; spectacles for the 4th of July and in honor of the accomplishments of explorer Henry Hudson and steamship inventor Robert Fulton; listening to chazzanut in synagogues; experiencing first automobile and train rides; owning pushcarts, and tasting ice cream.

Amid all this, how could one be an observant Jew in America? Tcharna concludes that it cannot be done simply by rote, that it is not enough to do what was convenient to do back in the old country. If Judaism is to be practiced, it must be understood; intelligent Jews must educate themselves about the whys and the wherefores.

From the beginning to end, this novel uses many Yiddish expressions. Lamdan (a Talmudic scholar) was the first on Page 1 and melamdim (teachers), ehrliche (honest) , hashkafah (world view), b’ezras Hashem (with God’s help), Aybeshter (The One who stands above) and nadan (dowry) were just some of the terms used on Page 352, the last of the book. While non-Yiddish speakers can work out such expressions from their context, a glossary of Yiddish terms would have been helpful.

With each episode about 4-5 pages long, the novel is easily read and provides numerous places for readers to pause.

If you would like to learn some Yiddish or about some important aspects of the Jewish-American immigrant experience, this is a book worth reading.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

I would like to purchase this book of stories. I have a Kindle. Is either paper or electronic version available yet?

Pingback: Staying frum as an American immigrant | Happy Independence Day