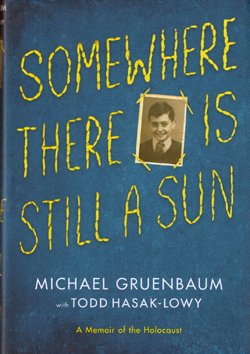

Somewhere There Is Still A Sun by Michael Gruenbaum with Todd Hasak-Lowy; Aladdin Books © 2015; ISBN 978-1-4424-8486-3; 378 pages including after words; $17.99

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – This book is what you might call a combination of a memoir and historical fiction—the two genres mixing in a tale intended for middle school students about a boy who survives with his family in Terezin, thanks to being able to avoid the transports to Auschwitz.

SAN DIEGO – This book is what you might call a combination of a memoir and historical fiction—the two genres mixing in a tale intended for middle school students about a boy who survives with his family in Terezin, thanks to being able to avoid the transports to Auschwitz.

The book combines the memories of an actual Terezin survivor, Michael Gruenbaum, with the writing skills of a fine story teller, Todd Hasak-Lowy. The writer interviewed the survivor at length, capturing his memories of specific incidents in Terezin, and then, feeling he didn’t have enough to sustain a book-length narrative, supplementing the story with his academic and personal research. The result was a book consistent with what already is known about Terezin (or as the Nazis called it “Theresienstadt”) that is mixed with Gruenbaum’s personal anecdotes.

As a pre-teen in Terezin, Gruenbaum didn’t have a sense of geopolitics, and knew very little about the world outside Prague, where he grew up, or Terezin where he was relocated with his family.

Inside the camp, he stayed in an all-boys barracks, led by a Jewish madrich who used the boys’ love of soccer to teach them how team work not only is a fundamental of sports, but a fundamental of survival in a world gone crazy. Essential to developing the spirit of camaraderie and mutual dependence among the boys was to make certain that they had only recreational contact with their parents—or in Michael’s case, with his mother and his older sister. Michael’s father, a Jewish communal leader, had been arrested by the Nazis in Prague and never returned home.

The story encompasses the deepening restrictions placed on Jews in Prague by the Nazis after their conquest of Czechoslovakia; how in his naiveté, young Michael was glad to be leaving Prague for Terezin; how the “show ghetto” of Terezin was organized; how madrichim hammered into the younger boys the necessity to keep themselves as clean as possible to avoid typhus; how everyone was always hungry; how word of an approaching “transport to the East” sowed panic, fear and depression among the Terezin inmates; how children (including Michael) performed in the opera Brundibar for representatives of the Red Cross; what it was like days before liberation when some of the walking skeletons from Auschwitz were marched back to Terezin; the effect of the tales they told; and, finally, the elation that came when Soviet soldiers liberated the camp.

While there are some graphic moments in the book, Gruenbaum and Hasak-Lowy told their story not to shock but to inform. As Gruenbaum’s generation passes away, these memoirs of the survivors—backed by solid historical research—will be important source material for children who unfortunately still must be initiated to the stories of the Holocaust so they can fathom the extent of man’s potential for inhumanity to man, and also, within that greater narrative, how the human spirit can be uplifted even in the grimmest of circumstances.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. You may contact him at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com