-64th in a Series-

Exit 51 Buckman Springs Road, Pine Valley~Gaskill Brothers Stone Store, Campo

By Donald H. Harrison

CAMPO, California – During the 1870s, the San Diego mercantile firm owned by Abraham Klauber and Samuel Steiner supplied groceries and dry goods to general stores all over Southern California and Northern Baja California. One of their best customers was a fellow Jew, Louis Mendelsohn of Rancho San Rafael, Mexico. Sufficient trust developed between the two mercantile concerns that Mendelsohn arranged to send $600 in gold, which was an enormous amount on Nov. 30, 1875, to Abraham Klauber, who operated the San Diego headquarters of the partnership. Klauber’s partner, Samuel Steiner, lived in San Francisco, where he purchased much of the company’s stock from importers.

The buggy in which Mendelsohn’s clerk, Henry A. Leclaire, and a former territorial governor of Baja California, Don Antonio Sosa, were traveling was intercepted, the gold stolen, and both men were murdered. The robbery and murders were part of a sinister plan by the bandit Cruz “Pancho” Lopez to acquire enough money, ammunition and supplies to enable his gang to attack and exploit the gold mines in the Mexican state of Sonora. Other customers of Steiner and Klauber—the brothers Silas and Lumen Gaskill who owned on the American side of the border in Campo a general store, blacksmith shop, post office, mill and small hotel as well as apiaries and cattle—were the next intended targets of Lopez and his gang.

David Klauber, a great-great grandson of Abraham Klauber, recounted in The Sounding, a 2009 history of his family, that the Gaskill Brothers were no easy pushovers. In fact, he reported, they “had previously earned their living with firearms, hunting game for wagon trains and shooting literally hundreds of bear for northern California ranchers.” Tipped off by a local worker that the Lopez gang planned to kill them and loot their store, the Gaskills made ready. They placed shotguns in strategic niches around their complex and went about their business. On December 4, 1875, Lopez and five other heavily armed riders crossed the border, where two wagons drivers awaited instructions to haul away the Gaskill Brothers’ goods.

David Klauber, a great-great grandson of Abraham Klauber, recounted in The Sounding, a 2009 history of his family, that the Gaskill Brothers were no easy pushovers. In fact, he reported, they “had previously earned their living with firearms, hunting game for wagon trains and shooting literally hundreds of bear for northern California ranchers.” Tipped off by a local worker that the Lopez gang planned to kill them and loot their store, the Gaskills made ready. They placed shotguns in strategic niches around their complex and went about their business. On December 4, 1875, Lopez and five other heavily armed riders crossed the border, where two wagons drivers awaited instructions to haul away the Gaskill Brothers’ goods.

As retold in Klauber’s book, over the next six minutes the sequence of events went as follows: When the Lopez gang arrived, Lumen was in the general store and Silas was at the blacksmith shop. Gang member Rafael Martinez, who had been pretending to shop, stepped outside when his six cohorts arrived. Lopez entered the store joined by Jose Alvijo and Alonzo Cota. Then Alvijo and Cota pulled their guns on Lumen, who screamed “murder” and dropped behind the counter. He tried to get to his weapon but Cota pulled him up and Alvijo fired a six-shooter right into Lumen’s chest, puncturing his lung. They left him behind the counter for dead, but somehow, although partially paralyzed, he survived, retrieved a shotgun, and crawled to a prone position just inside the door of the store.

Silas heard his brother’s shout and grabbed a shotgun in the blacksmith shop. Gang member Teodoro Vazquez fired at Silas, nicking his inner arm, and Silas blasted his shotgun, killing Vazquez instantly. He then chased Martinez and gang member Pancho Alvitro around the building, wounding Martinez badly enough that he stayed down on the ground. Alvitro hid for a while behind a woodpile, then headed to the store, where he came into the sights of Lumen’s shotgun. The subsequent blast severely wounded him.

In the meantime, two passersby came upon the scene. One held Silas’s shotgun; the other, a Frenchman, used his horse as a shield, and wounded Lopez as he came out of the store. Cota and Alvijo then found Lopez and the three of them engaged the Frenchman and Silas in a gun battle, until the bandits broke off the engagement. Those that could rode back to Mexico, where apparently the wagon drivers also had fled. Lumen meanwhile crawled to a trapdoor and dropped to safety in the stream that ran below the house.

Once out of range, Lopez yanked the seriously wounded Alvitro off his horse and shot him in the head, killing him. Alvijo, who had been left behind with wounds, was arrested and placed under guard with Martinez. That night vigilante ranchers broke into the temporary jail and lynched the prisoners together with the two ends of a single rope. About a month later, the Frenchman died of his wounds in San Francisco. Lopez subsequently also died from the infected wounds he had received from the Frenchman. Only Cota and another unnamed bandit got away.

In his book, David Klauber pointed out that the gunfight resulted in more deaths than Wyatt Earp’s famous shootout at the OK Corral approximately four years later.

The wounded Gaskill Brothers worried that Lopez would assemble another gang to stage another raid, and Silas wrote to Abraham Klauber in San Diego that “it seems rather tough that we can’t be protected in some way from being robbed and murdered here at home; minding our own business, does it not?”

He added: “I wish you would use what influence you can for us and see if we can’t get some protection in some way. The government ought to protect the Post Office and Military Telegraph here. They will have to be discontinued; probably both officers will be killed in the next attack.”

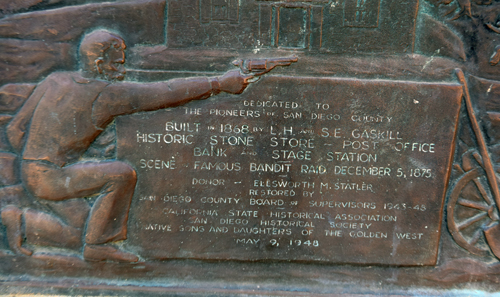

A ten-member committee of San Diego business leaders, including Klauber, persuaded the military to send troops to Campo. When a small military force arrived about a month later, tensions along the border somewhat eased. But, taking nothing for granted, the Gaskills decided to replace their frame store with a secure stone store, its walls four feet thick on the first floor and two feet thick on the second floor.

In 1898, The Klauber firm purchased the stone store from Ed Aiken, who was a successor of the Gaskill Brothers. The Klaubers sent, among others, Abraham’s son, Hugo Klauber, to run it for about two years. Aiken continued to work at the store for a brief period while Hugo familiarized himself with its operation. Campo, then, was cattle country, meaning that the ranchers only came into money once a year, after the cattle were driven to market. In the interim, they carried pass books on which the totals of their purchases at the store was noted on each occasion. A running total was shown for the year.

In a letter written June 26, 1898, Abraham gave his son some advice and spelled out the financial arrangements of their partnership.

I suppose it is unnecessary to say that the more rapidly you familiarize yourself with the details of the business, the better. Shall I send you my Spanish books? You will find them of great service when studied at the same time when you have a chance to put the theory into practical use. … Our proposition to you is as follows: We will furnish the capital interest to be charged and paid quarterly as an expense of the business at 7% per annum. Losses, if any, to be divided equally. I don’t see any chance whatever of a loss. The first $1200 per year (or 100 per month) of profit to go to you. Anything over 1200 and up to 2400 to go to us. If profits exceed 2400, they are to be equally divided. In other words if the profits were 3000 for the first year, you would get 1500 and we (K&LCo) 1500. All personal expense you will, of course, have to stand, such as board &c.

Melville Klauber joined his younger brother in Campo for the occasion of the store’s grand opening, recalling later that “we gave a free dinner to the inhabitants of that section at the Campo Hotel. In order to make the affair as successful as possible, there being a large crowd to take care of, H.K. {Hugo} and M.K. {Melville} helped to wait on the table and did whatever else was necessary to make it a success.” Hugo lodged at the same hotel, where the food was, frankly, awful.

A younger brother, Laurence M. Klauber, then 15 years old, came out to help in the summer of 1899. Sixty-one years later, he wrote an account for the San Diego Historical Society Quarterly detailing his impressions of the store.

At the left of the door, as one entered, there hung an olla of water. The olla was filled by carrying a bucket in from a nearby spring, in which resided the biggest goldfish you ever saw. Everyone entering the store paused for a drink from a dipper hanging by the olla, as a sort of greeting to those already within.

On three sides of the room there were counters. In front there were empty nail kegs intended for use as stools for the customers, but actually they were appropriated by philosophical cowboys resting from arguments with cows. At the right there was a wall rack containing rifles and shotguns, mostly museum pieces even for that day, although there were a few modern items, including an 1886 Winchester .38-55 that was Hugo’s pet.

There was no cash register, but under the counters, at four locations, there were cash drawers of the kind then used. Each of these had four or five finger hooks out of sight on the under side. If you knew the combination, and pulled the right hooks, the drawer came open, otherwise a bell rang. Beside each cash drawer, on a small shelf hidden under the counter and open to the back, there was a loaded six-shooter. I may say in passing, that although every cowboy wore a .44, I never saw any shooting during the three months I was there.

Eventually, Hugo returned to San Diego, where in 1899, he was drafted by the San Diego team in a four-team league to play first base in what turned out to be a 15-inning championship game against San Bernardino. The regular first baseman, Mike Donlin, had injured his finger so was sent to right field where he wasn’t likely to field as many plays. The San Diegans won the contest 1-0 with the very rookie Hugo Klauber making 17 putouts with nary an error. Donlin, by the way, went on to play for the fabled John McGraw’s New York Giants and later became a Broadway actor.

During Hugo’s tenure, the Campo store later was operated as part of the Klauber & Levi-owned Mountain Commercial Company, which also included other general stores in far-flung locales. Eventually, Henry Marcus Johnson partnered with the firm, serving as its general manager through 1925. Later, philanthropist E.M. Statler purchased it for San Diego County for use as a museum.

Although Hugo had made quite a name for himself as a semi-professional baseball player, he remained loyal to the family business and eventually rose to the presidency of the company that, after Steiner’s retirement, had been twice renamed, first as Klauber & Levi Company. After Simon Levi left to start his own grocery business, the firm became known as the Klauber-Wangenheim Company in honor of Julius Wangenheim, who married Abraham’s daughter Laura and became a business partner.

Today, the old stone store houses the exhibits of the Mountain Empire Historical Society, with a re-creation of a 19th century general store on the first floor, and exhibits about the area’s military history—including the story of the Buffalo Soldiers at Camp Lockett—retold on the second floor.

The townspeople of Campo periodically stage reenactments of the gun battle.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com