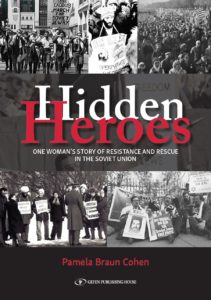

Hidden Heroes: One Woman’s Story of Resistance and Rescue in the Soviet Union by Pamela Braun Cohen; Gefen Publishing House © 2021; ISBN 9789657-023365; 393 pages including appendices and an extensive index.

By Toby Klein Greenwald

EFRAT, Israel — How did the prisoners of Zion and refuseniks have the courage, strength and dedication to apply to leave for Israel, study Hebrew and Judaism, and demonstrate for human rights, knowing that they would lose their livelihoods, and even to end up in the cruel gulag or in years of hard labor camps?

So I thought I knew something.

Reading Cohen’s book “Hidden Heroes” opened my eyes in a way that I didn’t think possible. Her stories are astonishing and spell-binding.

Cohen introduces us to the heartbreaking and inspirational stories of both the well-known personalities and of those whose names are less known to the public, who comprised the engine behind decades of perseverance and struggle. But Cohen, who lived in Deerfield, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, also tells the story of those who fought from her side of the world.

At her book launch in Jerusalem, Natan Sharansky recalled how his jailers had taunted him, “Look who is fighting for you! Just students and housewives.” But those students and housewives helped shake the world and change history.

Cohen takes us from the Soviet Jewish awakening — encouraged by Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War — through the Leningrad trials in 1970 of 11 people, mostly Jews, who had tried to hijack a plane “to marshal international attention,” including Sylva Zalmanson, her husband Edward Kuznetsov and Yosef Mendelevich. She concludes her book in the 1990s.

“[They were] Jewish moral giants who had pitted themselves against the Kremlin. But I wanted to know more…How had they come to make a decision that would result in years of imprisonment and hard labor in Siberia?” Kuznetsov and Mark Dymshits—the pilot who was to fly the captured plane, were sentenced to death, a sentence that was eventually commuted, due to international pressure. Cohen told this writer that while following the trials, she said, “The arrest of Jews…It wasn’t going to happen — NOT ON MY WATCH!”

Until then she was a happy Jewish mother and wife, involved in her synagogue, sent her kids to Jewish camps, and enjoyed family barbecues. Then her life changed forever.

She learned of the CASJ (Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry), the UCSJ (Union of Councils for Soviet Jews), and the SSSJ (Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry), all of whom pressed for the Jackson-Vanik Amendment. The UCSJ worked closely with Congress to ensure that the Soviets were not granted most-favored-nation-status as long as Jews could not emigrate freely.

She learned of the CASJ (Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry), the UCSJ (Union of Councils for Soviet Jews), and the SSSJ (Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry), all of whom pressed for the Jackson-Vanik Amendment. The UCSJ worked closely with Congress to ensure that the Soviets were not granted most-favored-nation-status as long as Jews could not emigrate freely. These organizations, and others, she writes, “managed to overcome the opposition of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the Nixon White House, big business and some Jewish Establishment leaders.”

In 1986 she became national president of the UCSJ. She was joined in her efforts by Marillyn Tallman, who had been her Jewish history teacher. Another of Tallman’s students was Tom Lantos, who later became a congressman from California and the co-chairman of the Congressional Human Rights Caucus.

Cohen says that people said, “You think you can take on the Kremlin?” But at her first UCSJ annual meeting she discovered that she was in good company with self-educated Sovietologists, savvy activists, doctors and business people and “strong, gutsy women…capable of facing down any KGB goon…”

Cohen overcame a natural shyness to reach out to Congressmen, senators, presidents and prime ministers. Her first trip to the Soviet Union was in 1978, with her husband, Lenny. They packed their suitcases with books, tallitot, tefillin, kosher mezuzah klafim, and also with cameras, tape recorders and other items that could be sold on the black market so refuseniks who had been fired from their jobs would be able to subsist.

Even the KGB knew about Pamela and her colleagues. On her trips to the USSR, she knew she was being followed and listened to.

Cohen and the Union of Council activists took a bi-partisan approach. In the fall of 1976, the wives of two refusenik-protesters who had been arrested, Boris Chernobilsky and Yosef Ahss, sent appeals to Betty Ford and Rosalynn Carter. Three weeks later the men were released.

Cohen, in an interview, tried to give credit to all those who helped. “President Reagan. His undiplomatic assertion that the USSR was an ‘evil empire’ gave him a diplomatic edge for negotiation on trade, arms control and human rights. George Shultz. Senators Henry Jackson and Frank Lautenberg established a firm foundation for the movement, the former by tying emigration to trade and the latter by redefining Soviet Jewish emigrants as refugees…Democrats and Republicans in the Senate and the House were united on the issue of Soviet Jewish emigration, Soviet human rights abuse, and Soviet anti-Semitism!”

Her husband Lenny and their children supported her every step of the way, even when evenings with friends morphed into Pamela’s lecturing. “What? You don’t know who Mendelevitch is?” When Cohen and her husband were on a romantic weekend getaway, she said to him, upon awakening, “Lenny, did I tell you that Lev Blitshtein went to visit Ida Nudel in Siberia?” That same Lev Blitshtein was denied exit by the Kremlin on the excuse that he had knowledge of “state secrets,” even though he was the only sausage-maker in Russia.

The morning after the bat mitzvah party of her daughter, Brooke, she writes, “Before she opened her gifts and we could relive the moment together, I allowed a limousine to carry me off to the airport for a flight to DC for our annual UCSJ meeting. Maybe that’s when I began asking the Almighty to take care of my children as I was trying to take care of His.”

Cohen and others were fervently committed that never again would Jews on the other side of the world be silent.

Even when the doors of the USSR started to open a bit in the 70’s and 80’s, it was a trickle compared to the hundreds of thousands of refuseniks still denied emigration visas. There were families torn apart.

Resistance was taking place all over the USSR. There were a large number of Jews living in Central Asia who were trying to get out. Cohen describes her first harrowing plane ride in snowy, stormy weather, to that area, when the flight attendant seated herself next to her, asking her questions that made it clear she was KGB.

Cohen writes, “It is written in Leviticus, ‘Do not stand by the blood of your brother.’ (19:16) We were impelled by an imperative to rescue…We were Jews. We were one people. They were ours.”

The American activists worked with European governments to try to get the Soviets to uphold the Helsinki agreements, which allowed for foreign nationals to have contact with Soviet citizens.

Cohen and her friends were always seeking creative solutions to help the refuseniks. On one occasion they got bear fat through the UCSJ’s council in Alaska for a Chinese homeopathic practitioner to treat Yaakov Mesh, to heal him from the brutal beating he had received in prison; they sent it with a tourist from Alaska going to Vladivostock. Mesh recovered.

The battle of the Kremlin against the Jewish refuseniks was also a psychological one, so the CASJ sent the refuseniks copies of the UCSJ’s statements, news articles, statements in the “Congressional Record,” and op-eds. They photographed the items, repacked the negatives so they looked like unused rolls of film, and tourists gave them to refusenik Yakov “Yasha” Goredetsky, who arranged for them to be developed and distributed to other refuseniks. She learned that these photos “lifted the morale, brought hope.” They did the same things with Hebrew audio tapes.

Cohen writes, “Once they applied to leave …refuseniks’ actions lit up the night sky like flashing comets. Every act of defiance reflected their inner liberation, their desire to live in freedom, in Israel… [Anatoly] Altman and Sharansky said they experienced that freedom to resist in rat-infested frigid prison cells.”

They had to contend with official rabbis in the USSR who were really working for the KGB, and an organization called the AZC were in fact “mouthpieces of the Kremlin…court Jews…” There were also informers. They were even concerned that the KGB would find a way to plant a mole inside of the UCSJ councils. Cohen says that “…the only freedom in the USSR was among the dissidents and refuseniks.”

Hebrew teachers like Aleksander Kholmyansky and Yuli Edelstein were arrested; a gun had been planted in Kholmyansky’s apartment and narcotics in Edelstein’s. Ari Volvovsky was sentenced to three years for teaching Hebrew.

There were interlocking threads. Cohen was called by a California congressman’s foreign affairs assistant who wanted to help a California woman who had been hit by a troika while visiting Moscow. The U.S. embassy was closed; Cohen found a Moscow refusenik, Leonid Stonov, to meet her husband at the airport. The assistant asked how to thank her. She asked for President Reagan to send a letter to Volvovsky at the labor camp. She only heard the end of the story in Laura Bialis’s film “Refusenik.” Ari was “invited” to the office of the camp commandant who asked if he was a friend of President Reagan’s. He said, “Well, if President Reagan wants to be my friend, I don’t mind.” He was released a few months later.

Pamela told me that some of the people who she feels were the most central in her organization were “UCSJ’s national director, Micah Naftalin, and David Waksberg, Lynn Singer, Glenn Richter, Judy Balint, Bob Gordon, Morey Schapir,a Ruth Newman, Helene Kedvin, Sandy Spinner, Babette Wampold.” She said they all had specialties.

“The next morning,” writes Cohen, “Mikhail’s story was on the front pages of the world’s press…But by the time Gorbachev let his sister leave, it was too late…” Cohen attended Mikhail’s shloshim in Israel. In 1987, writes Cohen, she believed the euphoria at the number of Jews who were leaving was “counterproductive,” as there were still half a million Jews waiting to get out, and savage human rights abuses.

Pamela drew closer to Judaism while working for Soviet Jewry.

“Volvovsky, Mendelevich and others who hacked their way through the thick, secular Communist propaganda were not only creating a path for their own Jewish Soviet people, but also for me, far away in Deerfield. Many of us in the West would later come to realize that in the process of rescuing Soviet Jews, we ourselves had been rescued.”

*

Toby Klein Greenwald is an award-winning journalist, an educational theater director and the editor-in-chief of WholeFamily.com. She and her husband live in Efrat and have children and grandchildren who live throughout the land of Israel.