By Nikolai Schweber

LOS ANGELES — Today, an Israeli construction worker from the small city of Hadera will vote on Israel’s future. What kind of future will he choose? He hasn’t decided yet, and the decision is paralyzing. With over 30 parties vying for parliament, he likely won’t decide which to cast his ballot for until he is in the voting booth.

“I hate the elections. It’s all bullsh*t,” he said when we spoke last week. He requested to remain anonymous.

Israel’s vibrant and robust democracy, often touted as the only democratic system in the Middle East, is in a slow-burning crisis.

In Israel, voters cast their ballots for parties, which earn seats in the Israeli parliament, called the Knesset. Party leaders then negotiate to form a majority coalition with at least 61 Knesset members, and one of the party leaders is chosen as Prime Minister. In recent years, parties have been repeatedly unable to form or maintain coalitions. Each time they fail, they automatically trigger a new election.

“There is no leader for the Jews [right now], not a real one,” says the construction worker.

This election is unprecedented; it is Israel’s fifth in the span of only three-and-a-half years. Neither of the two dominant factions have secured a clear victory in the last four elections, and polling indicates this year will be the same.

Despite having more than 30 parties to choose from, Israel is split nearly 50-50 between supporters and opponents of former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who, since his ousting in 2021, has led the parliamentary Opposition. The ex-prime minister and his ongoing corruption scandals are at the center of the political divide that has dominated Israel for five elections.

Netanyahu has been under indictment since 2019 for alleged bribery and fraud, which triggered the ongoing political crisis. He has vowed to reform the Israeli court system if returned to power, which observers say would eliminate many of Israel’s democratic checks and balances.

“The ability of government to deliver non-corrupt solutions that help a majority of Israelis” is at stake, says Professor Jonathon Rynhold, a political scientist at Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv.

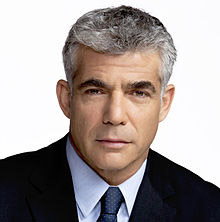

An ideologically diverse coalition of parties led by the centrist Prime Minister Yair Lapid opposes Netanyahu’s right-wing bloc. Lapid cobbled together this “change coalition” after the last election in March 2021. It incorporated all of the left and center parties, multiple right-wing parties, and, for the first time in Israeli history, an Arab party. These parties had only one goal in common: end Netanyahu’s 12 years in power.

However, the change coalition didn’t last. It collapsed in July after defections on the left and right, triggering today’s election. Lapid is scrambling to boost each of the small parties that formed the coalition, giving it his all to resurrect the alliance and prevent Netanyahu’s return.

The stage is set for another close finish that will leave Israel’s parliament without a clear governing majority for weeks or months, but with added stakes: Netanyahu has tethered himself to Israel’s once-untouchable extreme right-wing, promising to include them in his coalition and elevate their leaders to top posts if he is Prime Minister.

US officials worry that this move, if carried out, could increase anti-Israel sentiment in the West, thereby weakening the US-Israeli special alliance. Israeli observers foresee further deterioration of Jewish-Arab relations inside Israel. Today’s election could have serious, long-term implications for both Israel’s domestic stability and its position in the West.

How We Got Here: Four Elections and The Change Coalition

Netanyahu was a popular Prime Minister. During his 15 years in office, Israelis widely supported his handling of economic and security issues, as well as his COVID response. However, in 2016, his support began to erode after the announcement of police investigations into alleged bribery and fraud.

Investigations became indictments, alienating even close allies. His coalition disbanded, but subsequent elections in April and September of 2019 both resulted in deadlock. Neither Netanyahu nor his opponents were able to secure enough support to form a new governing coalition. As long as the parties failed to assemble a new majority, Netanyahu remained in power as head of an interim “caretaker” government.

Israel held a third election in March 2020, also tight, but this time centrist former general Benny Gantz, one of Netanyahu’s main rivals, accepted an unorthodox deal to break the deadlock. Gantz agreed to support Netanyahu as Prime Minister for one more year, and in return was promised that he would become Prime Minister after that. But his coalition deal with Netanyahu collapsed at the end of the year, and he never even became Prime Minister.

Instead, Israel was thrust into a fourth election in March 2021. This time, party leaders in the Knesset had had enough of Netanyahu. Enter the “change coalition.”

Benny Gantz and current Prime Minister Yair Lapid are the two most powerful figures in the “change” coalition. Barring a Netanyahu victory, they are the leading candidates to be Israel’s next Prime Minister. But they aren’t the only powerful figures in the anti-Netanyahu bloc. With margins so slim, even the smallest parties have immense leverage.

Building an anti-Netanyahu governing coalition is hard because Israel’s parliament has a clear right-wing majority. Any coalition that excludes Netanyahu’s Likud party, Israel’s largest political party, thus requires left and right-wing parties to unite.

This arrangement gives right-wing parties greater leverage and influence within any anti-Netanyahu coalition, as they have more incentive to defect. This is why the “change” coalition chose Naftali Bennett, who’s further right than Netanyahu, to serve as its first prime minister after the election last March. Bennett’s small, religious right-wing Yamina party, with only seven seats, was the most resistant to abandoning Netanyahu, and thus had the greatest leverage to extract concessions like the country’s top leadership position.

But Bennett’s Yamina was also the coalition’s weakest link. While Yamina got national leadership out of the deal, a number of Yamina members, under pressure from the right, defected, hobbling the government’s ability to function.

“Netanyahu put enormous pressure on two or three members of the coalition [from Yamina],” said Rynhold. They were targeted in speeches, in the media, and some of their families faced death threats and protests. These legislators ultimately withheld their votes on must-pass legislation, forcing the Knesset to call new elections.

Some coverage has focused on these specific legislative failures, but Rynhold argues they were merely the “arena of collapse,” not the cause. Policy compromises are always possible. In his view, the coalition fell apart due to the “personal politics of two or three people, either because they couldn’t take [the harassment] anymore or because they got greedy.”

The defections cost the coalition its majority, triggering the current election. Most of the “change” coalition’s member parties are still committed to opposing Netanyahu, and they’re hoping to form a second agreement after this election.

If they win enough seats, the same messy politics of a right-left alliance will be back, but this time they will be prepared. The left-wing party Meretz party has replaced less pragmatic members who created difficulties for the coalition. Yamina members did not know that their leader would negotiate them into a center-left government; at least this time, all of the right-wing parties know where they stand on Netanyahu.

Bibi’s Threats: Corruption and the Far-Right

A possible return to power by Netanyahu, popularly known as “Bibi,” has both Israeli and American observers on edge. Netanyahu is now seen as a threat to democracy in Israel because of his alleged corruption, proposed judicial reforms, and embrace of the far-right. In the US, pro-Israel Democrats have signaled that Netanyahu’s elevation of Israel’s far-right will fuel anti-Israel sentiments at home and abroad.

Netanyahu is currently involved in three separate court cases involving alleged corruption. In one case, he is accused of using his power to aid businessmen who showered him with expensive personal gifts during his time in office. The other two involve corrupt relationships with newspaper publishers, in which Netanyahu received promises of positive coverage in exchange for other favors.

In 2019, these indictments ultimately pushed several right-wing parties to abandon Netanyahu. “They’re opposing him because he’s corrupting the whole system and they think he’s detrimental to the future of Israel,” said Rynhold of the anti-Netanyahu right.

Since being indicted, Netanyahu has claimed that the courts are run by leftists and that the corruption cases are a ‘witch-hunt’ to keep him from power. He has gone even further in this election, proclaiming that he will pass several laws to restrain the power of the Israeli court system.

Most troubling, he has supported a law that would allow a simple majority in the Knesset to overrule any court decision, a long-time and controversial right-wing goal.

This would mean that the Knesset could grant Netanyahu a pardon or change Israel’s anti-corruption laws. Under this law, the Knesset could violate Israel’s unwritten constitution whenever it suits them. Israeli leaders would have the freedom to engage in open corruption and arbitrarily overrule court decisions they don’t like.

“Democracies do not fall in one day, or one month, it’s a process,” said Professor Rami Zeedan, who researches Israeli politics at the University of Kansas. “Changing the legal framework in Israel to benefit the cancellation of those trials against Netanyahu would put Israel on a very dangerous pathway.”

In the long-term, the loss of checks and balances could have severe impacts on Israel’s economy, security, and domestic stability.

“[Netanyahu] thinks he’s fighting for the state of Israel and thinks therefore he can do whatever the hell he likes. His role is to make sure he doesn’t go to prison [so that he] returns as Prime Minister, and everything else is collateral damage,” said Rynhold.

In order to return to power and stay out of jail, Netanyahu has also shown that he is willing to turn to anyone for help.

In 1971, an American-born Orthodox Rabbi named Meir Kahane moved to Israel. In the US, he had founded the Jewish Defense League, an organization which carried out assassinations and bombings against various perceived enemies. By the time he was elected to the Knesset in 1984, he had been convicted of terrorism conspiracy charges by both the US and Israel. The political platform of his party, Kach, included expelling non-Jewish people from Israel and banning sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews. The Israeli political establishment hated him, but his popularity grew among the working-class. Before the 1988 election, the Knesset passed a law banning parties that incited violence or racism from running in elections. The Kach party was no more, and two years later Kahane was assassinated in New York.

Though Kahane has been dead for over thirty years, “Kahanism” is still alive in the Israeli far-right. His followers have carried out major acts of terror, including the worst massacre of Palestinians by an Israeli and the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. None of his followers managed to win Knesset elections, that is, until last year.

In the last election, Netanyahu orchestrated a deal to merge two of Israel’s far right parties, Noam and Otzma Yehudit, into the larger Religious Zionism party. These parties were historically too small to get Knesset seats, but within a larger party they gained representation and relevance. Their party list, Religious Zionism, is projected to become the third-largest in the Knesset and will be essential for Netanyahu’s victory.

Noam is a socially conservative party known for its opposition to LGBT rights. Otzma Yehudit, the larger of the two, is considered the ideological successor to Kahanism.

Otzma Yehudit’s leader, Itamar Ben-Gvir, was a youth organizer with Meir Kahane and the Kach party. He first came to prominence in the 1990s, for his violent rhetoric against the soon to be assassinated Prime Minister Rabin.

He has since renounced violence but has a record of making violent threats against Israeli Arabs and made a career out of defending Jewish Israelis who murder Arabs in court. In the past year, he physically brawled with an Arab Knesset member and brandished a handgun at two Arab security guards. He has bragged about being indicted 53 times for a variety of incidents, most involving Arabs. He displayed in his home a portrait of Baruch Goldstein, the Israeli mass-murderer who shot 29 Palestinians as they prayed in a mosque.

Netanyahu once commanded the respect of much of the Knesset. Now, he is relying on some of its most toxic figures to solidify his majority. Previously, associating with such controversial politicians would’ve been a liability, but with margins so tight, Netanyahu needs new partners whose loyalty he can count on.

The far-right has their own reasons for supporting Netanyahu. “They think, [Netanyahu] is in such bad straits legally, he’ll give us the most… and so they support him,” said Rynhold.

In this election, Netanyahu has committed to including the far-right in his coalition and stated that he would elevate the once-untouchable Ben-Gvir to a top position in the government if elected. Ben-Gvir has stated he is most interested in being the Minister of Public Safety, which would give him power over the Israeli Police and prison system.

These figures’ extremism is further evidenced by US anxieties.

Senator Bob Menendez, one of the most pro-Israel US senators and a close Biden ally, told Netanyahu in a private meeting that there were “concerns” in the US about his far-right alliance. “Menendez wants to be a friend of Israel…and he’s saying [to Netanyahu] you’re going to make it difficult for me,” explained Rynhold. Menendez’s comments are not likely to impact much inside of Israel.

Netanyahu was reportedly frustrated by Menendez’s comments, and others were outraged by any US involvement in Israeli elections.

“I think that Israel is not American business…he’s talking like a patron,” said the undecided Hadera construction worker who identifies as politically right-wing. “[Religious Zionism’s voters] deserve representation,” he added, though he does not plan to vote for them.

His relaxed attitude towards the far-right is echoed by other centrist and right-wing Israeli voters. “[Ben-Gvir] is not really a radical [because] the situation here is terror[ism] daily,” said one young woman in Haifa, who plans to vote for Gantz’s National Unity Party and would like to see another unity government between Gantz and Netanyahu.

Rynhold, who specializes in studying the politics of the US-Israeli alliance, does not believe that there will be any sudden changes in the special relationship if Netanyahu makes good on his promise to elevate Ben-Gvir. For the US, this is about domestic politics more than strategic interests. American policymakers want to avoid headlines that could increase anti-Israel sentiment among the Democratic Party base.

The impact of the far-right on the US-Israel alliance could be more serious if their rhetoric translates into real policy. But these impacts could take years to materialize. In the short-term, any potential policy shifts would be more dire for Israel’s Arab citizens.

“[The far-right] might pass legislation that would make it harder for Arab politicians to run for office,” said Prof. Zeedan, who identifies as Arab-Israeli and specializes in studying Arabs in Israel. He also predicts land confiscations from Israeli Arabs would increase. Far-right and Likud legislators have also proposed deporting the families of convicted terrorists, a form of “collective punishment” which Zeedan says is undemocratic.

The far-right could be decisive come election day. But high turnout from other demographics could dilute the far-right’s impact.

Election Day: What to Watch For

Most polling shows neither bloc reaching a 61-seat majority on election day, though Netanyahu is projected to have a one or two seat advantage over his opponents. In an election this close, a few thousand votes here or there could determine which bloc is able to form a coalition.

Current Prime Minister Yair Lapid and the other architects of the anti-Netanyahu coalition are hoping for three key electoral outcomes to make their post-election negotiations easier.

While the center and left are firmly against Netanyahu, Israel’s right-wing majority is split. In this election, many right-wing voters feel “politically homeless,” split between Netanyahu’s far-right alliance and the anti-Netanyahu right-wing that is committed to allying with the center and left. These voters will be decisive for determining which faction is able to form a coalition after November 1st.

Netanyahu’s party, Likud, is the oldest right-wing party and the largest overall. Likud historically governed from the center-right and many voters like the Hadera construction worker still associate them with the widely popular, moderate leaders they grew up with in the 1970s and 80s.

In the wake of Netanyahu’s corruption charges, though, the Likud has found itself at odds with the traditional institutions of Israeli democracy. In Netanyahu’s final years in power, he and the Likud party increasingly espoused conspiracy theories about voter fraud and a rigged, leftist court system determined to undermine right-wing policies.

There are clear parallels between Netanyahu’s rhetoric and that of former President Donald Trump in the US.

“Trump is popular [on the right] in Israel, so Netanyahu sort of gets legitimacy from acting in ways that he would not have acted six or seven years ago,” says Rynhold.

Likud is projected to remain Israel’s largest party, but some formerly loyal voters are turned off by Netanyahu’s antidemocratic conspiracies.

“All the trials and all the BS that he has had around him are not honorable for someone in public office,” said the construction worker from Hadera. As a self-identified right-wing voter, he is torn between policy and principle. He also believes that the anti-Netanyahu right-wing parties have their own corruption problems.

The smaller parties are split on religious lines: the secular right (outside of Likud) uniformly opposes Netanyahu, while the religious right backs him even more uniformly than in previous elections.

Naftali Bennett, the prominent right-religious leader who made the “change” coalition possible, is retiring and his Yamina party has dissolved. The religious right-wing parties are now united under the Religious Zionism party banner, dominated by the aforementioned anti-LGBT Noam and ultranationalist Otzma Yehudit.

The other major religious parties, the ultra-Orthodox Shas and United Torah Judaism, are also firmly with Netanyahu.

The secular right-wing camp, which opposes Netanyahu, includes both moderate and hardline conservatives. The Yisrael Beitenu party was a reliable coalition partner of Netanyahu with a platform further to his right, but they have firmly opposed him since his corruption cases surfaced. The moderates have coalesced behind Benny Gantz’s National Unity Party, which leans heavily on its leaders’ military credentials and their pitch for uniting the country.

If the secular and center-right can increase their power, Benny Gantz or Yair Lapid have a good shot at leading Israel’s next coalition. Netanyahu is hoping the undecided right will shift towards the revamped Religious Zionist alliance.

Arab Israelis make up about 20% of the population, and most of them vote for parties that specifically represent Arab interests.

In the current Knesset, Arab representatives are divided between Ra’am, an Islamist party that is in the “change coalition,” and the Joint List, an alliance of the other three major Arab parties that remained in the Opposition. The parties in the Joint List are all more secular and liberal than Ra’am on social issues, and are more aggresively pro-Palestinian, putting them at odds with the Israeli mainstream.

Unlike the other Arab parties, Ra’am and its calculating leader, Mansour Abbas, are religious and lean conservative on many issues. But Abbas’ political philosophy values power above all else. He believes that the only way to achieve real change for Israeli Arabs is from inside the system.

However, his Machiavellian philosophy also means that Abbas is not necessarily a reliable coalition partner. He previously held talks with Netanyahu after the last election and has signaled willingness to do so again. He would likely not be accepted into a coalition with the anti-Arab far-right, Professor Zeedan said, but as long as Netanyahu has 61 “Kosher hands” to approve his government, Ra’am may still be willing to lend support from outside the majority.

Keeping Abbas onboard will be essential for the anti-Netanyahu coalition.

Other Arab parties have a weaker position. The current Joint List parties will not join any coalition under any circumstances, and the Jewish leaders won’t have them anyway; their positions on Palestine are too controversial. But they could still aid the “change” coalition in the same way Ra’am could potentially aid Netanyahu, by lending supportive votes while still remaining in the Opposition. So, more seats for the Arab parties is still a positive for the anti-Netanyahu bloc.

Most polling so far suggests that Arab turnout will be low this year. It was already low in the last election, too, at 44%, and some polls have predicted that for the first time Arab turnout could sink below 40%.

The low turnout forecast comes down to disillusionment with the Arab leadership. The Joint List announced its dissolution earlier this year, meaning that the Arab parties are now split among three different party lists. Arab voter turnout is highest when the Arab parties run unified and has historically declined when they split up.

Because the Arab parties are split, each one must also struggle to cross the 3.25% vote threshold required to earn Knesset seats. If any of them fail to meet the mark, then tens of thousands of Arab votes will be wasted and their Knesset seats lost.

Arab voter turnout will thus be one of the most important election-day indicators for which bloc has an advantage. The key to motivating Arab voters is simply “that people think it will make a difference,” says Rynhold.

“At the moment, Arab citizens do not feel that Abbas being part of the government made a real difference — they’re wrong, but that’s what they feel!” says Rynhold.

The government did approve new investments in Arab communities, but this hasn’t yet yielded noticeable changes that the Arab leaders can point to. “Nothing changed in regard to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict…and not a lot has changed in terms of the rhetoric and investment towards the [Arab] localities…and confiscation of lands,” notes Zeedan.

With many Arab voters planning to skip election day in protest, Arab parties are desperately trying to turn out the vote. Ra’am is touting the public investments it secured for Arab communities. Other Arab parties are relying on the fear of the anti-Arab far-right and the threat of missing the threshold as motivators. Some polls have shown momentum behind increased Arab turnout, but it may be too late.

“It’s too late now, unless the right-wing makes a mistake,” says Professor Zeedan.

This is all good news for Netanyahu, and he is attempting to avoid any last-minute mistakes that could shift this trend. In the past, Netanyahu’s infamous fear-mongering about Arabs “voting in droves” actually motivated more Arabs to come out and vote against him. This time, he is encouraging Arabs to vote for him, arguing that he can deliver the economic and public safety investments that they prioritize.

The final polls before the election still show Ra’am holding its four current seats and the other Arab parties losing two of their current six. Arab turnout will be essential for current Prime Minister Lapid and the anti-Netanyahu bloc. They will need Abbas’s Ra’am, and they will need the other Arab parties to take up Knesset seats that would otherwise go right. On the other hand, if Arab turnout is as low as predicted, Netanyahu and his allies will be advantaged.

The left-wing has less moving parts than the Arab parties or the right. Most left-of-center voters will support current Prime Minister Yair Lapid’s centrist Yesh Atid party, the second-largest in the Knesset. The two genuinely left-wing parties, the center-left Labor Party and the more socialist Meretz, are also reliable “change” coalition partners. Given left-wing voters’ unified concern about Netanyahu, turnout shouldn’t be an issue.

But the Israeli left is dwindling. Meretz may even fail to cross the 3.25% threshold to get Knesset seats, which would mean thousands of anti-Netanyahu votes gone to waste. Lapid had urged Labor and Meretz to merge to avoid this possibility, but Labor refused.

A failure to cross the threshold by Meretz would be the biggest blow to the anti-Netanyahu bloc’s chances of forming another majority. The final election polls predict Labor with 6 seats and Meretz with 4, both parties losing seats from their current total. Things are at a tipping point.

What’s next?

All eyes are on undecided voters like the Hadera construction worker. If right-wing voters like him go for Netanyahu’s opponents, Arab voters show up, and leftist voters push Meretz over the threshold, then Israel’s democracy may continue chugging along. The bitter polarization of the last few years may even begin to dissipate.

“If Netanyahu can’t win, I think this would be the beginning of the end for him,” says Rynhold.

Even if Netanyahu becomes Prime Minister though, the worst could be avoided if he goes back on his promise to include the far-right in his coalition.

The anti-Bibi right could potentially enter a coalition with Netanyahu in a bid to keep the far-right out of power. Ra’am’s leader, Abbas, could theoretically make the same calculation.

“The worst fear is…with the independence of the judiciary and the fabric of relations between Jews and Arabs in Israel,” said Rynhold. He also fears that any long-term possibility of peace between Israel and the Palestinians could evaporate if Netanyahu and the far-right stay in power for an extended period.

The far-right would likely support a legalization of further Israeli settlement in the Palestinian territories, and potentially revisit Netanyahu’s controversial proposal to annex the West Bank, added Zeedan.

Since its inception, the citizens of Israel have debated how to reconcile its competing identities as both a Jewish state and a democratic one. The far-right has a simple answer: forget liberal democracy and go all-in on ethnonationalism.

Bibi is along for the ride. He doesn’t believe that this will undermine Israel’s domestic stability and foreign alliances, or he just doesn’t care. In his view, Israel will be okay as long as he is in control. And anything goes if you’re the victim of a legal “witch hunt,” right?

Now it’s up to Israeli voters, right and left; religious and secular; Arab and Jewish; to decide for themselves: democracy or demagoguery. The future awaits.

*

Nikolai Schweber is an aspiring foreign policy analyst and journalist currently working for a DC-based polling firm. He is particularly interested in Israel and the Middle East region, and he spent a summer conducting political science research at the University of Haifa. He graduated from UC Berkeley in 2022, where he wrote for the Berkeley Political Review. He is currently based in Los Angeles.