Editor’s Note: This is the 9th chapter in Volume 3 of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com.

Editor’s Note: This is the 9th chapter in Volume 3 of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com.

Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Volume 3, Exit 40 (Birmingham Drive): Starbucks

From the northbound Interstate 5, take the Birmingham Drive exit, turn left on Birmingham Drive, follow to San Elijo Avenue. Turn left. Starbucks will be on the left side in the Seaside Market at 2081 San Elijo Avenue.

ENCINITAS, California –While the flavors of Starbucks’ coffee come from such far-flung locales as Brazil, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Indonesia and Kenya, the company itself has a decidedly Jewish-American tam.

Jews have been involved from the company’s beginnings as a specialty purveyor of coffee beans through its expansion to a giant global company with 33,833 stores in 80 countries as of November 2021. Of those, 15,444 were located in the United States, including this one at 2081 San Elijo Avenue in the Cardiff=by-the-Sea neighborhood of Encinitas.

Some of the landsmen who were crucial in the evolution of Starbucks included Zev Siegl, Howard Schultz, Jack Benaroya, Herman Sarkowsky, Sam Stroum, Harold Gorlick and his nephew, jazz musician Kenny G. Later in the company’s history came Leonard Maltz, Howard Behar and Dan Levitan.

Sigl, who taught history in Seattle public schools, was the son of Henry Siegl, a longtime concertmaster for the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, and Eleanor Shapiro Siegl, an educator who founded a Seattle pre-school called “The Little School.” Along with his friends, Jerry Baldwin, and English teacher, and Gordon Bowker, an education writer turned advertising executive, Siegl was a coffee afficionado. They were particularly impressed with the coffee varieties sold by the Berkeley, California-based Peets Coffee and Tea. In 1971, following Peets’ lead, the Seattle threesome opened the first Starbucks, which sold freshly roasted, rich, aromatic coffee beans as well as equipment for home brewing.

For a while, Siegl was the company’s only paid employee as Baldwin and Bowker continued at their day jobs. The name, “Starbucks” conflated the name of the early 20th century Starbo mining camp with “Starbuck,” the first mate on the Pequod in Herman Melville’s famed novel Moby Dick. For their logo, they chose a long-haired siren surrounded by the company’s original name “Starbucks Coffee, Tea and Spice.”

Siegl lectured customers enthusiastically about where the coffees had come from the differences in their tastes, and how best to brew them at home. As the company grew, he became a vice president and director, but eventually sold his share of the company to partners Baldwin and Bowker.

Howard Schultz, who would become the most important person in Starbucks evolution, had grown up in the Bayview Projects in the Canarsie section of Brooklyn, New York. His father, Fred, worked at a series of low-paying jobs, including driving a truck. His mother, Elaine, was a homemaker who raised Howard and his two siblings. Thanks to some prowess in football, Howard was able to go to Northern Michigan University, although he was not a star. After receiving a bachelor’s degree in communications, he worked first for Xerox and later as a general manager for the Swedish company, Prestop, in the Hammarplast division selling housewares.

One of the items Hammarplast carried was a drip coffee maker that Starbucks, then a small company, was purchasing and selling at an impressive rate. Schultz decided in 1981 to fly to Seattle and visit the company, which by then had four stores. He fell in love with the gourmet dark-roasted coffee concept. Over the next year, Schultz worked on persuading the two partners to hire him to head marketing and retail sales. The move meant a cut in salary for Schultz, but h gained a small equity position in the company.

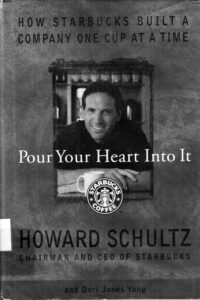

In his 1997 memoir, Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time, Schultz wrote about a momentous trip to Milan, Italy, during which he was impressed by the Italians’ love for expresso coffee shops. “I discovered the ritual and romance of coffee bars in Italy,” he wrote. “I saw how popular they were, and ow vibrant. Each one had its own unique character, but there was one common thread: the camaraderie between the customers, who knew each other well, and the barista, who was performing with flair. At that time there were 200,000 coffee bars in Italy, and 1,500 in the city of Milan, a city the size of Philadelphia. It seemed they were on every street corner, and they all were packed.”

In his 1997 memoir, Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time, Schultz wrote about a momentous trip to Milan, Italy, during which he was impressed by the Italians’ love for expresso coffee shops. “I discovered the ritual and romance of coffee bars in Italy,” he wrote. “I saw how popular they were, and ow vibrant. Each one had its own unique character, but there was one common thread: the camaraderie between the customers, who knew each other well, and the barista, who was performing with flair. At that time there were 200,000 coffee bars in Italy, and 1,500 in the city of Milan, a city the size of Philadelphia. It seemed they were on every street corner, and they all were packed.”

After visiting numerous coffee bars, Schultz said, “I had a revelation. Starbucks had missed the point – completely missed it. This is so powerful, I thought. This is the link. The connection to the people who loved coffee did not have to take place only in their homes, where they ground and brewed whole-bean coffee. What we had to do was unlock the romance and mystery of coffee, firsthand, in coffee bars. The Italians understood the personal relationship that people could have to coffee, its social aspect. I couldn’t believe that Starbucks was in the coffee business, yet was overlooking so central an element of it.”

After numerous entreaties from Schultz, Baldwin and Bowker allowed him to open a combination package and drinks store in 1985 at Fourth and Spring Streets in Seattle. Although it was successful, the senior partners did not want to get into the restaurant business. With their encouragement, Schultz opened his own coffee house called Il Giornale (after a daily newspaper in Italy). Besides Starbucks, which invested $150,000 in Schultz’s venture, other investors were three well-known Jewish philanthropists in Seattle: Jack Benaroya, Herman Sarkowsky, and Sam Stroum. Another Jewish investor was Harold Gorlick, whose nephew was jazz musician Kenny G.

Schultz and Kenny G became friendly, so much so that the musician entertained at subsequent sore openings. His recorded music became a feature of the music played at Il Giornale and later at Starbucks.

In 1987, Baldwin and Bowker decided to sell their Seattle stores, the roasting plant, and the Starbucks name while retaining the whole bean stores and the brand that they had acquired in the interim from Berkeley entrepreneur Alfred Peet. Schultz was able to raise $3.8 million to purchase the store and merge Il Giornale and Starbucks. Although he had a sentimental attachment to the Il Giornale name, he recognized that for non-Italian conversant Americans “Starbucks” was easier to pronounce and to remember.

Leonard Maltz was another Jewish community member who became involved with Starbucks. He was hired in 1987 to serve as the company’s executive vice president. Years later, he would head a subsidiary organization, Borderless Investment Group, that opened Starbucks franchises in China.

Even while Schultz was expanding the number of company-owned outlets to meet his board’s expectations of growth, he successfully implemented a health plan for employees, paying 75 percent of their premiums with employees contributing the other 25 percent. He also introduced a plan by which employees could annually receive stock options equivalent to 12 percent of their annual salaries and later 14 percent. When the value of the stock went up, the options became more valuable. Both moves were intended to make Starbucks employees feel less like employees and more like co-owners of the business. In fact, Schultz decreed the word “employee” should be stricken from the company’s lexicon. Thereafter, they would be known as “partners.”

“I tried to make Starbucks the kind of company I wish my dad worked for,” Schultz wrote. “Without a high school diploma, he probably could never have been an executive. But if he had landed a job in one of our stores or roasting plants, he wouldn’t have quit in frustration because the company didn’t value him. He would have had good health benefits, stock options, and an atmosphere in which his suggestions or complaints would receive a prompt, respectful response.”

Jeff Brotman, one of the original founders of Costco, joined the Starbucks board and was a mentor to Schultz. Another Jewish community member of the Starbucks team was Howard Behar, who lectured Schultz that as important a it was to maintain the high quality, taste, and aroma of the beans used in Starbucks drinks, it was also important to listen to the customers. Schultz had resisted offering a skimmed milk option with the café lattes because he felt it didn’t provide the same rich taste as whole milk. Behr said that made no difference. Diet-conscious customers wanted the skimmed milk, and they should have it. Behar prevailed.

After five years, Schultz took the company public, with the stock symbol SBUX. One of the investment bankers who engineered the initial public offering was Dan Levitan, another member of the Jewish community, whom Schultz described as a “mensch.”

Thereafter, in the time frame described in the memoir, Starbucks expanded in 1992 from Seattle and Chicago to San Diego, San Francisco, and Denver. It teamed with Capitol Records in 1995 to make CDs of the music played in its stores. That same year it partnered with Pepsi Cola to create and sell a bottle Frappuccino for sale in supermarkets and created a coffee-infused Double Black Stout with Seattle’s Redhook Ale Brewery. In 1996, it teamed with Dreyer’s Ice Cream to produce five varieties of coffee-flavored ice creams. It also contracted in 1996 with United Airlines to serve Starbucks coffee on flights.

In the realm of philanthropy, Starbucks created an ongoing partnership with CARE to assist the populations of coffee-producing countries.

In the years following publication of that memoir, according to Wikipedia, Schultz took an eight-year break from serving as Starbucks chief executive officer to concentrate on opening stores internationally and to participate in an ownership group for the Seattle Supersonics of the National Basketball Association and the Seattle Storm of the Women’s National Basketball Association. He feuded with the State of Washington over his demand that the state government help finance a new arena. In 2006, he sold the two teams to an Oklahoma City ownership group, resulting in the Supersonics being renamed as the Oklahoma City Thunder beginning in the 2008-2009 season. The Seattle Storm subsequently was sold to a Seattle group and remains in that city.

Schultz returned as Starbucks CEO during the financial crisis of 2008 and the following year, he fired numerous store managers, closed down hundreds of stores, and temporarily shut down all Starbucks to retrain employees on the proper way to make expresso.

In 2014, he created the Starbucks College Achievement Plan in collaboration with Arizona State University. It enabled employees working more than 20 hour a week to take video classes at ASU, with Starbucks footing the cost of tuition.

That same year, he wrote For Love of Country: What Our Veterans Can Teach Us About Citizenship, Heroism and Sacrifice. In 2019, he followed up with From the Ground Up: A Journey to Reimagine the Promise of America. He was considered a likely independent presidential candidate in 2020, but ultimately he declined to run, explaining that he didn’t wish to siphon votes from Democratic nominee Joe Biden. “Nobody wanted to see Donald Trump removed from office more than me,” he said.

Schultz and his wife, the former Sheri Kersch, co-founded the Schultz Family Foundation, which has focused on employing youth under the age of 24 and helping veterans to transition to civilian life. Schultz was honored by Israel during its 50th anniversary celebration in 1998. A year later, AIDS Action conferred its National Leadership Award on him for his philanthropic efforts to battle AIDS. In 2015, Fortune magazine described him as the most generous CEO.

The Schultzes have two children. In October 2020 Forbes estimated that the boy from the Bayview Project had compiled personal assets worth $4.3 billion, making him the 209th richest person in America. Among his assets is PI, a 77-meter superyacht built for $120 million.

In 2022, Schultz returned as CEO of Starbucks at $1 a year, pending the hiring of a new CEO to succeed Kevin Johnson who retired March 16, 2022.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com