Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of stories based on editor Donald Harrison’s 50th anniversary cruise with his wife Nancy from Sydney, Australia, back to San Diego, and the people they met and places they visited along the way.

By Donald H. Harrison

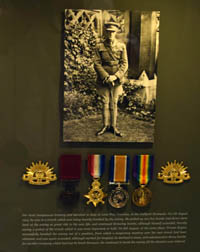

SYDNEY, Australia – Dedicated as the Maccabean Hall in 1923 by Sir General John Monash, a Jew who perhaps was Australia’s greatest military figure, the Jewish Museum of Sydney today devotes much of its space to the exploits of Australia’s Jewish servicemen and to the history and aftermath of the Nazi-perpetrated Holocaust in Europe. The multi-level museum is successful in personalizing both the stories of war and of racist genocide.

Monash was the World War I lieutenant general credited with designing the Allied offensive against Germany at the Battle of Amiens (France) in August 1918, an offensive that relied upon surprise and the coordinated use of artillery, tanks, and infantry. Historians mark the battle as a turning point of the war, which ended only three months later with an armistice on November 11. Many Australians also associate Monash with the development of ANZAC (Australia-New Zealand Army Corps) pride, when as a newly minted general in 1916, he passed out ribbons for his troops to wear on April 25 to mark the one-year anniversary of Australian and New Zealand forces landing together on the Gallipoli peninsula. That operation was part of a broader, unsuccessful Allied effort to capture from Turkish and German forces the Dardanelles, the narrow sea passageway that divides European Turkey from Asian Turkey and leads from the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus (adjacent to Istanbul) all the way to the Black Sea. The joint landing helped stoke the national consciousness of both Australia and New Zealand, which then were British colonies.

Our guide through the museum was Michael Gold, a retired principal of public high schools in the largely Jewish neighborhoods in Sydney of Dover Heights and Killara. Gold, who rose from working class beginnings as the son of a steel metal worker, also has served as president of Sydney’s Great Synagogue.

In a section of the museum honoring Australia’s war dead, he pointed proudly to the name of Evan Altshuler (L/Sgt), who was killed during World War II when “his ship was torpedoed, even though it had a Red Cross on it.” Altshuler was the uncle of Gold’s wife, for whom her brother was named.

Among Jewish soldiers who survived the war were brothers Eric and Stanley Goulston, who both were honored as men of medicine. During World War II, serving in Australia’s medical corps, Eric was detached to Ethiopia, where he served as a battlefield surgeon for units of Ethiopian guerrillas fighting to liberate their country from the rule of Fascist Italy. In the 1960s, he became the first professor of surgery at Haile Selassie University in Addis Ababa. In Australia, he had a wide ranging surgical practice and was recognized for pioneering a procedure to repair cases of congenital tracheoesophageal fistula. Eric lived a few weeks past his 100th birthday, “and the rabbi and I visited him on his 100th birthday at his home, where he elected to spend his last days.” Brother Stan served in the Australian Expeditionary Force’s medical corps in the Middle East, earning a military cross. As a civilian doctor, he later co-founded with Sir William Morrow the first gastroenterology department in Australia, at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

Stopping at a display about Leonard Keysor, Gold said that Keysor had immigrated to Australia from England, and had a passion for playing cricket. At Gallipoli, “as the Turks were throwing the equivalent of hand grenades into the trenches, he would jump up and catch them and throw them back. Although wounded, he did that for about 50 hours on the front, and he won the Victoria Cross,” Australia’s highest military award.

Another display concerned Gregory Sher, who “was the first Jewish soldier to die in combat since World War II and the eighth Australian soldier to die in Afghanistan.” The display included his uniform and boots.

Jews have served in the Australian military forces in higher percentages than their representation in the overall population, according to Gold. “Jews have been accepted in Australia,” Gold commented, adding that military service is considered an appropriate means to express appreciation. Over the years, he said, Jews have been encouraged by rabbis of the Great Synagogue to such patriotism.

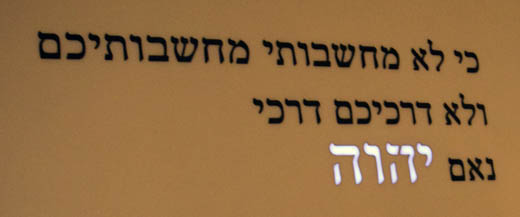

Before turning to the Holocaust section of the museum, we visited a section providing a general orientation about Judaism for non-Jewish visitors. One display within that section quotes biblical passages about God, for example: Isaiah 55:8, which states (per the Art Scroll Tanach) “For My thoughts are not your thoughts and your ways are not my ways – Hashem.” The top bar in the hei of God’s Hebrew name is intentionally broken so that the assembled letters do not actually spell the Divine name, but rather an approximation of the name. Gold explained: “You shouldn’t destroy anything that has the name of God, so what they had to do was to make it so that His name was not complete. So, if this ever has to be taken down, or is destroyed, it will be kosher.” He added that for the same reason, worn out siddurim (prayer books) are not destroyed, but rather are buried in a cemetery, just as a human being would be, with appropriate prayers.

In the museum’s Holocaust section, there are exhibits and a fold-out brochure with portraits of many of the survivors who settled after the war in Sydney. Indicating one of the photos, Gold said: “Here’s a woman I grew up with. She didn’t know her background at all. Eventually, she learned that her parents were not her biological parents. In Jewish fashion, she was raised by the brother of her father. She came across a photo in which she was with a group of other children in Theresienstadt [a ghetto and concentration camp in Czechoslovakia], and she began piecing things together.”

As a matter of policy and possibly safety, the museum does not disclose the exact names of the Survivors.

Another portrait was of a “woman who was in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, and when they were liberated, she was 18 years old, and weighed 28 kilos [61.7 pounds]. She acquired a blanket, woven from the hair of inmates destined for death, to cover her skeletal form and to provide warmth. Her mother died on the day of liberation.”

Another survivor, who visits the museum from time to time to talk to visiting school children, tells of lining up for soup, and intentionally lingering at the back of the line. The reason: the watery soup had only a few potato peels, and that which was ladled from the bottom of the pot was likely to have more peels than the soup at the top.

We passed through a gallery documenting the rise in Germany of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party, and the increasingly repressive decrees aimed at dehumanizing the Jews. Gold stopped in front of a display case telling the story of William Cooper, an elder of the Aborigine people.

“He was elderly and in ill health, but he led a delegation to the German consulate that was based in Melbourne at that time with a petition from the Aboriginal people of Australia,” said Gold. “In 1938, the Aboriginal people were not being treated all that well themselves, and yet, he stepped out with a petition. He was denied entry to the consulate, but he made a fuss and drew attention to it.”

The petition read: “We the undersigned, on behalf of the Aboriginal inhabitants of Australia, wish to have it registered and on record that we protest wholeheartedly at the cruel persecution of the Jewish people by Nazi government in Germany and we plead that you will make it known to your government and its military leaders that this cruel persecution of their fellow citizens must be brought to an end.”

Smitten with this member of an oppressed minority, who stood up for the Jews, the Jewish community of Australia has heaped honors and awards upon William Cooper and his descendants.

In the section about Kristallnacht—the pogrom in which synagogues and Jewish businesses throughout Germany were destroyed—is a story about an Australian immigrant who was 4 years old at the time of Kristallnacht. His parents decided to flee Germany, and they went to Shanghai, China, from whence they later immigrated to Australia.

About another Australian immigrant is the story of how she changed her identity with a false passport, taking a very Christian-sounding pseudonym: Christianne De la Croix.

One of the displays at the Jewish museum is a teddy bear. It was owned by a 2-year-old boy who escaped Budapest in 1944 with his parents, going after the war to a Displaced Persons camp, and eventually to a new life in Australia.

In a section about the mass shootings by the Einsatzgruppen (Mobile Killing Units), the story is told of the town of Sernicki in the Ukraine, where more than half of the 1,500 inhabitants were Jews. The Germans rounded up the Jews, had them dig their own mass graves and strip naked, whereupon they were mowed by machine gun bullets. Years later, in Adelaide, Australia, some women survivors recognized a man they said was the Sernicki forest warden, who assisted Nazi troops in rounding up Jews and executing them.

Australia convened a special investigation into war crimes. It sent an archaeologist, a forensic scientist, and a police officer, who also was a good photographer, to Sernicki, where after searching and digging they found the mass grave. Amid the skeletal remains was a bottle of Schnapps, which had been tossed into the grave after the bodies. Gold offered two alternative explanations. Perhaps a soldier threw the bottle into the grave as a further sign of contempt for the Jews just executed. Or, perhaps, the soldier was so emotionally affected by the scene that he got drunk to try to erase it from his stricken conscience. In my opinion, the first scenario was more likely, but what do you think?

As a result of the investigation, charges were brought against Ukrainian immigrant Ivan Polyukhovich, 75, in a war crimes trial. It took the jury less than an hour to find him not guilty, notwithstanding the documentary evidence that had been brought back from the Ukraine.

There are many touching stories about Holocaust survivors who later became Australians. Another that captured my imagination was about a woman who found a coin in a concentration camp. She traded it to another inmate for a slice of bread (in that camp, inmates normally received two slices). Then she traded the slice of bread for half a head scarf. In the barracks, when guards would not see her, she fixed the half-scarf over her shaven head, and thereby reclaimed—at least fleetingly—her Jewish womanhood.

*

Harrison is editor and publisher of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Thanks, Don

Btw our friend Peter Kubiek, z’l, passed away in late December

Pingback: The Jewish victims in an Australian tragedy | San Diego Jewish World