-First of two parts-

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Boarding a comfortable but fast boat that would circumnavigate the South Pacific island of Niue, Noa and Esther were pleased with their earlier meeting with the country’s premier, who had promised his government’s cooperation as they explored the possibility of installing a desalination plant on the island. However, he warned them that due to the atoll’s geography, rising as it did straight up from the Pacific Ocean, there were very few spaces for beaches or natural harbors. So, he said, finding a suitable location for a desalination plant might be very difficult indeed.

As representatives of the San Diego-based Rabinove Foundation, which channels billions of dollars into ecologically sound projects, Noa and Esther brought different perspectives to their work. Noa was an Israeli who had pioneered a desalination process that collected and utilized the salt and minerals separated from the ocean water, much as minerals and salts from the Dead Sea were process, packaged and utilized for skin care treatments. Noa also was blessed with a through knowledge of the Bible. Very recently, she had married Joseph Rabinove, the multibillionaire whose Six Points Enterprises funded the Foundation. Esther had grown up in Rancho Santa Fe, an affluent suburb of San Diego. She was the younger of Rabinove’s two children. Her brother Steve was Rabinove’s heir apparent who, in the guise of a financial writer, traveled the world to scout business opportunities for his father. Esther typically minded the home front, serving as her father’s executive assistant at the Foundation’s building in the Sorrento Valley neighborhood of San Diego. Esther was intimately familiar with her father’s many charitable enterprises. Her father had recommended that Esther accompany Noa on this trip to Niue. He believed it would help the two most important women in his life to get to know each other better. Although it was still a bit awkward for her, Esther had accepted Noa as her stepmother.

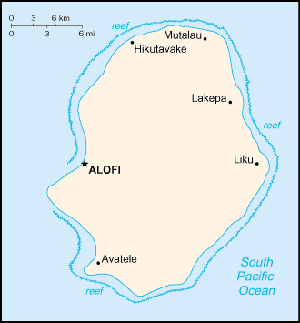

In consultation with their guide, Matafetu, the two women decided to circumnavigate the island from Alofi harbor in a clockwise manner, in that way passing the 14 villages that each elect one representative to the Legislative Assembly. Six other members of that body are elected at large, and together, all 20 decide who of their number shall serve as Premier and who shall be the Speaker of the House.

There are different ways to conceptualize Niue’s shape. You might think of it as a person’s face, looking to the west. In such a conceptualization, the capital city, Alofi, sits right above the bridge of Niue’s nose. Or you might think of it as a clock’s face, somewhat battered. In that event, Alofi is located at the 9 position of the clock face.

“Look there,” said Matafetu. “Do you see a canoe emerging from a nearly hidden passage where the atoll meets the waterline? The canoe is stored in the calm waters of the Makato Chasm, which is like chasms found all around the island. Running parallel to the coast, these chasms not only provide our canoes with safe shelters, but also are good places to find shrimp and other crustaceans. So, in that sense, Makato is a beautiful place, but sadly, nearby, it also is a very ugly place, because it is one of the major dumping sites on the island. The solid waste brought there becomes a home for rats, flies, and other pests. It also threatens to leach into our island’s freshwater supply, which is in a natural aquifer sitting near the top of the atoll. Our people know that solid waste hurts our environmentally conscious island, but what can they do? Studies after studies have called for the creation of a proper, regulated landfill, but we don’t have the money to accomplish that. So, the problem gets put off year after year. How long will it be before we will pay the cost of our negligence?”

Esther and Noa looked at each other. Perhaps creating a proper landfill might be a project for the Rabinove Foundation to consider, even if a desalination plant proved impractical.

“Up ahead,” said Matafetu, “is the Vaila Cave, which is a tourist destination.Our whole island is covered with scenic walks that lead to interesting photogenic places, Vaila Cave, which is known for its rock pools, being among them. At low tide, it’s a snorkeler’s delight because its pools are deep enough to swim in, while its coral wall keeps it safe from the incoming tides. Now we’re coming up on Makato Point, which is considered the northern boundary of Alofi Bay. Beyond it, is an interesting historical site, the grave of Nukai Peniamina, who went to Samoa where he was converted to Christianity by the London Missionary Society. He is credited with bringing Christianity to Niue, and in the process helping to end a cycle of warfare among the northerners and southerners.”

“You know, Noa, at the northern edge of San Diego County, right along the coastal road where our Camp Pendleton Marine Corps base meets the Orange County line, there is a marker at a place called La Cristianita,” Esther recounted. “It marks the spot in July of 1769 where Father Francisco Gomez, who was assigned to the overland exploration of the Spanish soldier Gaspar de Portola, spotted two dying little girls of the Acjachemen people —- better known today as the Luisenos – and persuaded their mother to allow him to baptize them before their deaths. Because it was the first Christian baptism in Southern California, the spot was later deemed worthy by the state’s historic commission to be permanently marked. However, the spot is on the Marine Corps base, which is closed for security reasons to outsiders. So now, in San Clemente, which is a city in Orange County, just north of the San Diego County line, they’ve put up another monument, which is accessible to the public about the first Baptism. It explains that the actual spot is at Camp Pendleton.”

“Do they have monuments to the first Jews too?” Noa asked.

“No, but the first Jew who settled in San Diego – Louis Rose – has had numerous places named for him, including Rose Canyon, Rose Creek, the Roseville section of Point Loma, and the Robinson-Rose House, which serves as the visitor center at Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. Personally, I like the idea of honoring people of many faiths who contributed to the history of our region. I can understand why Niueans would want Peniamina’s gravesite also marked.”

Continuing north to approximately the 10 position, the tour boat crossed the boundary line of Makefu, one of Niue’s 14 traditional villages. According to Matafetu, the village’s population was less than 100. Makefu is closely associated with the shimmering, turquoise water of Avaiki Cave, sometimes known as “The King’s Cave,” because it has two pools, one of which was reserved exclusively for Niue’s ancient kings to bathe; the other available to their staffs.

“That reminds me of King Herod’s fortress on Masada,” said Noa. “Even though he had built extensive bath house structures on that desert mountain for members of his court and the general public, he also had his own, personal bath on a lower terrace of Masada. Interestingly the bathhouses were a blend of Roman architecture and Jewish religious requirements. The baths were constructed so you had to step down into them, fulfilling the religious requirements for a ceremonial mikveh. I went to mikveh at Congregation Adat Shalom in La Jolla before my wedding to participate, you might say, in the ritual of a new birth. It was exhilarating.”

“New birth,” Esther repeated to herself silently. “I wonder if I will ever be reborn into a life that I truly desire?”

Matafetu pointed to a spot inland of the reef, where there was an irregularly shaped opening to a cave – perhaps 100 feet wide and 50 feet high in the shape of a gerrymandered U.S. congressional district. “Palaha Cave,” he said, “has two levels of chambers, and is famous or its stalactites, which stand inside like monuments.”

“I’ll bet he’ll tell us that old joke about the difference between stalactites and stalagmites,” Esther whispered to Noa.

“The cave of Palaha was probably the place where two brothers hid after stealing from the nearby village of Tuapa a talisman that our ancestors called ‘Takamutu,’” the guide said. “It was a simple looking object—no more than a shaft topped by a round head rather than by a spear. But among the people of the village, the Takamutu was considered a sacred object. If you were a farmer and you had it in your possession, you would have a good harvest. And if you were a warrior – as the people of Tuapa and other cities to the north were then – the Takamutu would sustain you in battle. At that time, the people of the north, known as the Mutu, and those of the south, the Tafiti people, didn’t like each other and warfare broke out frequently. Somehow the brothers from the south stole into Tuapa and when the keepers of the fire weren’t paying attention, they took the Takamutu from its honored place. They disappeared into the darkness of the Palaha cave, from which they made their way by sea back to their own people. The people of Tuapa were so disheartened by the theft, that they lost confidence in their ability as warriors. Today, the Tafiti and the Mutu are reconciled. Whatever our differences we are one people, Niueans. But that’s not to say, that people from Tuapa are afraid to fight. Prominent in the village is a memorial to residents who fought and died with ANZAC forces in both World Wars as well as the Vietnam conflict. Another point of interest, just in front of the church, is the gravesite of Niue’s last king, Togia, who died in 1917 – seventeen years after he ceded his kingdom to Britain.”

“You know,” said Noa, “the Philistines believed that by stealing the Ark of the Covenant, they could demoralize the Israelites, and drain them of their will to fight. Of course, the effect was just the reverse!”

“Any idea where the Takamutu is today?” asked Esther.

“This is not known. Perhaps it stands in a cave as a stalactite. Or perhaps it hangs from a ceiling as a stalagmite,” Matafetu responded. Smiling, he added, “I overheard that you are expecting this riddle: ‘How can you remember whether a formation is a stalagmite or a stalactite? Because they hang from the ceiling, stalagmites have to hang on with all their might.’ I should also tell you that Tuapa is one of the few places on Niue where you can find a sandy beach –- Hio Beach – but only at low tide. To get there you need to navigate your way through the cave system – and be sure to wear reef shoes.

“Now we are coming up on another of Niue’s 14 towns, the one that is known as Namukulu. It has the smallest population of all the villages – in the 2017 census, there were only 11 people, mainly members of my own family. On any given day at one of Niue’s most popular visitor attractions, the Limu Pools, there will be more snorkelers than we have residents. The snorkelers like to swim among the sea snakes and eel, butterfly and trigger fish. The sea snakes, by the way, are harmless.”

“As I understand it,” commented Esther, who was more focused on politics than fauna, “each of the villages sends one representative to Niue’s Legislative Assembly. So, in terms of sheer voting power, your 11 people in Namukulu are very powerful – akin to the power that small states exercise in the United States Congress. Although members of the House of Representatives are elected by population, each state – no matter how few or numerous its citizens — gets two U.S. senators. That same disparity is reflected in the Electoral College, which is how someone can be elected as President of the United States, even without winning the popular vote.”

“Donald Trump was the most recent example,” commented Noa.

“Yes, Hillary Clinton received about 3 million more popular votes than he did in the 2016 election.”

Matafetu chose not to answer Esther’s implied question. Instead her resumed narrating the tour. “Hikutavake, here near the northwest corner of Niue, is another small village with a population of perhaps 50 or less,” he said. “It is perhaps best known for the often-photographed, seaside Talava Arches, which are reached by following a path through the forest to the Matapa Chasm and then wading beneath high cliffs to the arches. If you enjoy snorkeling, it is another wonderful place to visit, but here, as elsewhere, you must be careful to wear reef shoes when you walk on the coral.”

Their power boat rounded the island to the northern coast, past Vaikho, which leads inland to Toi, which Matafetu described as “another of Niue’s severely underpopulated villages, with perhaps about 25 people or less. The village is named for the flowering Toi tree, which produces berries beloved by pigeons. Farmers believe when the Toi starts budding, it is the best time to plant taro.”

“For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven: a time to be born, a time to die, a time to plant, and a time to pluck up what is planted,” Noa quoted.

“That’s from ‘Turn, Turn, Turn’ by the Byrds, isn’t it?” asked Esther.

“Actually, no, it’s from Ecclesiastes in the Bible, from which the Byrds adapted their song,” Noa smiled.

“It’s beautiful.”

“We’re coming up on Mutalau, on the northeast corner of the island,” Matafetu commented. “Compared to some of the villages we have passed, Mutalau is fairly large, with a population of perhaps 100 people. It is best known for the vanilla vines that are grown here – vanilla is one of Niue’s few exports. You remember passing the site of Peniamina’s grave; well, it was here in 1846 that he first landed on his way home from Samoa. In Mutalau, the day he landed – the last Saturday in October – is celebrated as Gospel Day, the day Christianity was brought to the island. Peniamina had tried to land earlier on other parts of the island, but he was driven away.The village of Mutalau was the first to accept him. Mutalau, which was much more populous in those days, assigned 61 warriors to protect him from those who wanted to kill him for preaching a new religion.

“As you may have heard, the word Niue translates roughly as “Behold the Coconut,” and between here and Lakepa, we’ll pass our island’s largest concentration of coconut groves as well as a famous cave at Anatola, which ancient legend says was the home of a dangerous god,” Matafetu continued. “Here,” he said, handing coconuts with straws to Noa and Esther. “We drink the water from the coconut, but that is only one of its remarkable uses. Look at the fibers that cover the coconut. Those we use to make string or rope. The shell itself can be utilized as a vessel for carrying or storing liquids. The soft, white meat of the coconut can be eaten as you dig it out, or it can be cooked with vegetables to make a delicious stew. We also compress the meat into an oil, which can be used for massages and as an ingredient for sun tanning lotion. Just as we don’t waste any part of the coconut, this is also true about the coconut tree. Those large leaves can be used as thatch on the roof of a hut. The branches can be made into brooms. If a coconut tree ever falls, its thick wood can be used for a variety of purposes, one of my favorite being the stout, sturdy walking sticks on sale at gift shops for navigating your way through the forests and chasms of our island.”

After a pause during which Esther and Noa contentedly sipped on their coconuts, while enjoying the sea breeze, Matafetu continued his narrative “We have an interesting custom here in Niue: each of our 14 villages, including Lakepa, has an annual ‘show day,’ at which there are hakas and other dances, plenty of food, and the display and sale of crafts. The women of Lakepa are particularly renowned for weaving hand fans. The 9-mile cross-island road through forests and fields between Lakepa and our capital of Alofi is never so crowded as it is on the date of Lakepa’s annual show day. People from the States might think we have rush traffic! On any other day, life in Lakepa, with fewer than 100 residents, is fairly quiet. They have an old abandoned school that was converted into tourist lodging, a memorial for Lakepa residents who fought in World War I with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, and a 40-meter high Internet tower that connects Mutalau, Lakepa and Liku to the cyber world.”

Farther south came the village of Liku, which is the terminus of another cross-island road to Alofi. At the 3 o’clock position of the island, the village is fairly spread out, with most families’ stucco bungalows placed on concrete slabs and roofed with corrugated iron. “One of the crops grown in Liku is called “noni,” which is a fruit that is part of the coffee family,” Matafetu said. “You know how you like to open a can of coffee and breathe in its aroma? Well, don’t do that with the noni fruit, which has an odor so foul that kind people call it ‘cheese fruit’ and not-so-kind people call it ‘vomit fruit.’ Despite its bad smell when it ripens, noni is said to have healthful properties and is used throughout Polynesia as a folk remedy for a wide variety of maladies including diabetes, high blood pressure, and assorted aches and pains. There are many kinds of noni on the juice market, all of them mixed with some kind of sweet juice to mask noni’s unpleasant smell. What brings visitors to Liku, other than its annual show day, at which noni juices are sold, is the Hikugali Sculpture Park. There you will find a work called ‘Protean Habitat’ by the conservationist and artist Mark Cross is the most prominent feature,” Matafetu lectured.

“Approximately 10 meters in diameter, and centered on a vertical pole, 16 beams extend in every direction, giving the initial impression of a spaceship ready to be launched from an alien nest. However, strange fruit hangs from these branch-like beams: metal trash from our throwaway society that includes such items as pots, pans, old light fixtures, coffee pots, microwave ovens, fans, video players, bicycle wheels, license plates, diverse automobile parts, computer mother boards and aluminum cans. Visitors are invited to attach their own refuse to this growing monster, which is an analog for the evermore polluted lands and oceans. Cross is a New Zealander and his wife, Ahi, is a local weaver. Along with some friends, they conceptualized the Sculpture Park as a place both to showcase indigenous art themes and to address contemporary issues. I’ve visited the gallery in Alofi where the Crosses exhibit, and I must say I am one of his fans. Even as he addresses the absolute need to protect our planet in that amazing sculpture, he also addresses a similar theme in some of his paintings. Renowned for picturing the reflections of coral and sunlight off Niue’s shimmering waters, he places in some of his paintings the garbage that floats in from the sea – a potent protest against waste and disposables.”

“The Great Pacific Garbage Patch!” exclaimed Esther.

“Exactly what I was thinking,” Noa commented. “Imagine how he could draw the world’s attention to that!”

“Mark Cross has another monumental sculpture – it is a giant coconut crab, many, many times its actual size, which he has created to draw attention in New Zealand to the fact that if they are taken from Niue without regard to their population growth, they could soon become extinct. We call them ‘uga,’ but they also are known as coconut crabs because they actually wrap their claws around the trunks of coconut trees to wriggle their way up. They are quite delicious.”

“You won’t have to worry about me devouring the supply,” commented Noa. “I keep kosher.”

“What is that?” asked Matafetu.

“It is the set of dietary rules that certain Jews—but not all—observe in choosing what foods to eat.”

“You mean as in the Bible, when the Israelites are commanded in Leviticus not “to eat any animal that has a split hoof completely divided and that chews the cud?”

“Yes, except, I think that the relevant passage for the coconut crab is Levitius 11:9, in which we are commanded not to eat anything from the water that does not have fins and scales.”

“But the coconut crab is not from the water; it is a terrestrial species,” said Matafetu.

“Oh,” said Noa, “in that case, I think Leviticus 11:41 applies: “Everything that creeps on its belly, and everything that walks on four legs, up to those with numerous legs, among all the teeming things that teem upon the earth, you may not eat them, for they are an abomination.”

“Do you also observe this custom?” Matafetu asked Esther.

“No, I am more secular in my food choices.” Esther responded. “But I’m curious, Why do the crabs climb the coconut trees? Do they eat coconuts?”

“They’ll eat many things that they find on the ground, but they do not have the ability to crack the coconuts. The real reason they climb coconut trees is to escape from predators, especially when they are young and relatively defenseless.”

“Are New Zealanders particularly fond of eating them?”

“Less so the New Zealanders than the many Niueans who have moved there either to go to college or to find jobs. There are many more Niueans in New Zealand than there are in Niue, although many of them come home for visits, especially during the Christmas and New Year’s holidays. One of my sisters is there studying graphic arts, and my older brother works as a computer engineer in New Zealand. I miss them both very much, but I understand their decision to seek opportunities and to build their careers.”

“Do you think if there were good-paying jobs here in Niue to return to, they would return?”

“Yes, without doubt, I’m sure they would.”

“Where are we now?” asked Esther.

“We’ve just finished circumnavigating the northern half of Niue,” said Matafetu. Next, we’ll visit the lands of the Tafiti.

(End part 1)

Pingback: Fiction: Jewish perspectives on Niue, Part 2 - San Diego Jewish World