Editor’s Note: Crossing borders and migration have been crucial over the centuries for the survival of the Jewish people. Now, other peoples throughout the world, whether because their lives are in danger or because their countries of origin offer no opportunity for economic advancement, are fleeing some nations and being blocked from entering others. The issue of migration is particularly acute along the U.S.-Mexico border because refugees from developing nations envision the United States as a beckoning land of opportunity, just as generations of Jews before them thought of America as the “goldene medina.” In this series to be published on an occasional basis, we will meet people who have been influential in defining issues of migration at the San Diego/ Tijuana border. True to our readership, we will not neglect those instances when our subjects interacted with or were influenced by the Jewish community.

-First in a Series-

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – In 2009, Enrique Morones, then the leader of Border Angels, was presented by Mexico’s President Felipe Calderon with an award conferred by the Human Rights Commission of Mexico. The impressive ceremony in Mexico City honored Morones’ decades of work protecting undocumented migrants who brave harsh terrain and insufferable temperatures to seek new lives in the United States. In an acceptance speech, Morones urged Mexicans not to come to the United States, telling them that they were needed to build their own nation. ‘We are Mexicans, and Mexico’s future is here in Mexico, not America,” he pleaded. “Mexicans, do not go.”

Morones asserts a dual identity. He was born and raised in the United States, more specifically the Golden Hill neighborhood of San Diego, and is an active American citizen. But as he also proudly declares, he is a Mexican, holding since 1998 the first certificate ever issued by Mexico acknowledging dual nationality.

To his fellow Americans, Morones preaches a message as urgent as that he has for Mexicans: Treat those migrants who do come to America with compassion and dignity. Don’t treat them as criminals but rather as fellow human beings who are seeking to better their lives and those of their family members. Build bridges, not walls. Reach out to them, with open hearts.

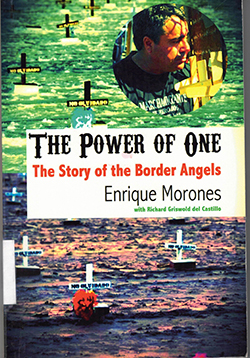

Over lunch at D.Z. Akin’s Delicatessen, where he ordered a bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwich, Morones told San Diego Jewish World reporters Mimi Pollack and me about the steps in his life that led to him becoming an impassioned advocate not only for migrants but also for Latinos facing discrimination in the United States. Information included in Morones’ 2012 memoir The Power of One: The Story of the Border Angels supplemented our interview.

Over lunch at D.Z. Akin’s Delicatessen, where he ordered a bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwich, Morones told San Diego Jewish World reporters Mimi Pollack and me about the steps in his life that led to him becoming an impassioned advocate not only for migrants but also for Latinos facing discrimination in the United States. Information included in Morones’ 2012 memoir The Power of One: The Story of the Border Angels supplemented our interview.

Morones’ father, Luis, had worked in Mexico City for AeroVia Reforma, a predecessor airline to Aeromexico. After moving to Tijuana to make arrangements at its airport, he was offered a job in San Diego working for the Mexican Fish and Game Department. Told the position paid three times what he was making with the airline, he informed his wife, Laura Careaga, that the family would stay in San Diego only temporarily. “Temporary became permanent,” Enrique Morones chuckled. Eventually Luis Morones returned to Aeromexico to work in its San Diego operations. In addition to his two children born in Mexico, he and Laura had Enrique and two other children born in the United States.

Enrique Morones had a Catholic education, graduating in 1974 from St. Augustine High School. He said that Catholic theology made a deep impression on him, particularly the example of compassion found in Matthew 25:35: “For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in.”

He subsequently earned a bachelor’s degree in international marketing from San Diego State University in 1979, and a Master’s Degree in 2002 from the University of San Diego in executive leadership. In the interim, he served as a marketing director based in the Del Mar Heights office of Krystal Hotels of Mexico, which operated properties in Puerto Vallarta, Ixtapa, Mexico City, and Cancun. “I would travel to their four hotels and travel all over the world to promote them.” From there he was recruited by the Presidente chain, which soon merged with Stouffer Hotels to become Stouffer Presidente, with properties in Cancun, Cozumel, Ixtapa, Oaxaca, Mexico City, Los Cabos and Loreto. However, Nestle, the food company that owned Stouffers, decided to get out of the hotel business, a decision that prompted Morones to create his own private marketing company in Los Angeles called Mexico-One Destination. He signed up independent hotels in Mexico and developed a program to promote all of them.

Next, he returned to San Diego, taking a volunteer position with the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. In December 1994, software executive John Moores purchased the San Diego Padres from Tom Werner, and installed Larry Lucchino as the team’s president and Bruce Bochy as its manager. Morones suggested to Lucchino that the Padres build fan loyalty across the border in Mexico, resulting in Morones being hired in 1995 as director of Latino marketing. Among his innovations: a Padres store in Tijuana’s Plaza del Rio; cross-border buses to the Padres games in San Diego, and the scheduling of three Major League Baseball games between the Padres and the New York Mets in August of 1996 in Monterrey, Mexico. But, as successful as these programs were, there was a conflict between Morones’ role with the Padres, and his off-the-field activities as an advocate for human rights. To relate that part of Morones’ story, we must go back three decades to the story of Roberto Martinez, who was Morones’ role model.

*

Martinez had moved in 1965 with his family to the Carleton Oaks section of Santee, a city on San Diego’s eastern border. One of the first Latinos to settle in Santee, he was greeted with graffiti that insulted his family as “wetbacks,” and included swastikas. A youth division of the Ku Klux Klan made life miserable for any non-White children. This was when Santee earned the nickname “Klantee,” a sobriquet the city still is trying to live down. Martinez spoke out against racism and such discriminatory practices, eventually taking a position as the San Diego director of the American Friends Service Committee, which, among other causes, advocated for the rights of border-crossing migrants. Martinez’s willingness to put himself on the front lines in the face of racism and unadulterated hate won admiration and support from Morones, who at that point stayed mainly in the background, contenting himself with delivering food and clothing to the needy in Tijuana. Years later when Morones was awarded with Mexico’s human rights award, he dedicated the honor to Martinez’s memory.

While engaged in collection and delivery of necessities to Tijuana’s poor, Morones was asked whether he also had a program for the migrants who worked in the flower fields of Carlsbad by day and slept in that city’s rugged canyons at night. As told in his memoir, “I went into the canyons and was mortified and very sad to see men, women, and children living in open air in the dirt. How could it be possible that the wealthiest country in the history of the world allowed the very people who picked our food, took care of our children, and built our homes to live in canyons without shelter, running water or electricity? How do you communicate with your families back home? Are you getting medical attention? Do your children go to school? I asked and was overcome by the sweetness, kindness, and sincerity of these hard-working people, the salt of the earth, the best of ours, our indigenous brothers and sisters.

“It was right then and there that the Border Angels was born, in the canyons of Carlsbad in 1986. We did not have a name yet but a movement was beginning,” Morones wrote.

In addition to expanding donations of food and clothing to the field workers in Carlsbad, Morones embarked upon an ambitious project to create water stations on the American side of the rugged U.S.-Mexico border in the mountains and deserts east of San Diego. Here migrants had regularly perished from thirst and heat exhaustion, unprepared for triple-digit temperatures in the summer, nor for freezing mountain temperatures in the winter.

Often asked if the program creating water stations had the effect of encouraging undocumented migration, Morones had a succinct answer: “I can guarantee you that not one person has ever crossed for the water.”

Morones said that at a rally in East Los Angeles College in 1993 to rename Brooklyn Avenue as Cesar Chavez Boulevard, he was seated next to Ethel Kennedy, the widow of former U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who asked him about his work in the canyons and at the border. In describing his work, he also said that as a matter of preference he prefers to stay in the background and let others enjoy the limelight.

He quoted Mrs. Kennedy as responding, “No, people do need to know about it. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, ‘Injustice here is injustice everywhere,’ and my husband really believed that. He took a bullet for it, and his brother [President John F. Kennedy] took a bullet for it. I recommend you get out there on the front lines and tell people about this… You’re going to have enemies, of course, but some of those enemies are going to be from your own community. They’re going to get jealous or not going to understand or be envious. But you have the passion, so I recommend that you get at the forefront of this issue.”

*

The job with the Padres lasted until 2001 when Moores stayed on as the baseball team’s owner and Lucchino went to Boston to become the president of the Red Sox. Morones said that Moores gave him an ultimatum: he could continue to work for the Padres, or he could continue his controversial work as a well-known advocate for migrants and the Latino community. Morones chose the latter.

That same year, Don Francisco, the Chilean host of the popular Spanish-language television show Sabado Gigante [Giant Saturday], seen throughout Latin America, interviewed Morones about his work leaving water for migrants and dubbed him the Border Angel. Morones responded that the title better belonged to the organization that he had founded, rather than to himself personally. Thereafter those who left life-saving water in the deserts of California became known as The Border Angels.

Morones, a bachelor who had three longtime girlfriends, but never felt having a family was in the cards, thereafter threw himself into advocacy. He was often a guest on American television interview shows to discuss legislation affecting immigration. And he accepted an offer from radio station owner Jaime Bonilla to become an afternoon talk show host himself on a program called Morones por la Tarde [Morones for the afternoon]. Roberto Martinez was his first guest, and over the course of the show he interviewed such others as Dolores Huerta of the United Farm Workers; Congressman (and later unsuccessful presidential candidate) Denis Kucinich, U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Jeffrey Davidow, and California Supreme Court Justice Carlos Moreno. He also interviewed some adversaries, including Bryan Barton, a member of the Minuteman group that self-appointed themselves as guardians of the border.

With Dolores Huerta he helped to organize annual Migrant Marches, which were multiple-automobile cavalcades along the border and into the American interior, with stops and press conferences to publicize the plight of the migrants. Drawing a lesson from the 1993 Steven Spielberg-produced movie Schindler’s List, Morones began highlighting the tragic stories of individual migrants who lost their lives or were separated from their families during the migratory process. “Like most people I thought how horrific that period in world history was; I think in terms of numbers—millions of people died during the Holocaust, about two-thirds of them being Jewish. I think how horrible that is. But it’s hard for me to capture what one million is, or even a thousand. I could picture maybe fifty or a hundred, but for me to imagine ten thousand or more people dying [in the North American deserts], it’s hard to understand on a human level. But in Steven Spielberg’s movies you see the individual stories, and I thought that’s very powerful to have these individual stories that personalize a mass tragedy.”

So, along the marches, he told such stories as that of 5-year-old Marco Antonio Villaseñor, who was among some 80 people crowded into the back of a truck stopped in Victoria, Texas. He asked his father for water, but he didn’t answer; nor did the next man, nor the next. The reason was that they were among 18 men who already had died from heat exposure. Not much later little Marco also succumbed. The horror was reported in Jorge Ramos’s book Dying to Cross: The Worst Immigrant Tragedy in American History.

Morones said the “most famous” of the Migrant Marches came in February 2006, which left Friendship Park at the junction of the Pacific Ocean and the U.S.–Mexico border and “covered 10,000 miles in a round trip that involved 111 cars, 40 cities and 20 states.”

Today, Morones is no longer affiliated with Border Angels from which he retired in November 2019. That organization now is run by different leaders. Meanwhile, More directs Gente Unida, which focused in 2020 on the upcoming election between Joe Biden and then President Donald Trump. Morones was involved in hosting podcasts with such guests as singer Linda Ronstadt, actress Eva Longoria, and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. After Biden won the election, Gente Unida developed programs in support of the poor, including a “1,000-mile caravan to San Quintin in Baja California to deliver 1,000 toys to 1,000 Oaxacan children.”

While unhappy with some aspects of President Biden’s policy toward migrants – including the retention of Title 42 of the public health law allowing Immigration officials to turn asylum seekers away from the border out of fear of spreading the coronavirus pandemic – Morones says “there is a huge difference between this administration and the previous.”

Under Trump, he said, “there were children dying in custody; they were pepper spraying people through the wall – it was horrible. … The worst of the worst was Trump, his racism, his sexism, all of it. Joe Biden has a good heart. He is trying to do the right thing. He stumbles sometimes, like anybody, but I think he is surprising a lot of people including me.”

Morones also involves himself in local issues. When students of Coronado High School, with a predominantly White student body, recently threw tortillas at the predominantly Latino students of Orange Glen High School of Escondido following a regional championship game which Coronado won, Morones declared it an instance of racism, dismissing the words of the man who brought the tortillas that it wasn’t meant that way – that in fact, tortilla showers are customary at some colleges like UC Santa Barbara. The man who brought the tortillas said that he, himself, has one Mexican parent.

Said Morones: “I’ll say this about the kids from Orange Glen; they kept their cool. If that had happened to me, I would have been in a fist fight. That’s a tribute to their parents and the coaches. … They weren’t only throwing tortillas, they were throwing racial slurs, and the people who were being hit, that was battery.” Further, he said, “the person who determines if it is racist is not the person committing the act; it is the person receiving the act. They are the ones who can interpret it, who can tell whether it is racist or not.”

Notwithstanding incidents such as these, Morones declares himself hopeful about race relations. In his book, he cited the case of President Bill Clinton’s college friend, Alan Bersin, a member of San Diego’s Jewish community, who served initially as the United States Attorney in San Diego, and later was named by President Barack Obama as the Commissioner of the sprawling Customs and Border Protection agency. Bersin was nicknamed the “Border Czar.”

One year when Bersin came back to San Diego to address the Catfish Club (an African-American organization) and UC San Diego’s Institute of the Americas, Morones had to cancel his planned attendance because of the death of his friend and mentor Roberto Martinez. “I asked Alan to mention the passing of Roberto Martinez in his talks, which he did. This was evidence of the new and improved Alan Bersin. In order to have change you need to work with both sides.”

In addition to his roles as the founder of Border Angels and Gente Unida, Morones also is the organizer of the House of Mexico, which is one of the organizations awaiting a constituent cottage at the House of Pacific Relations in Balboa Park.

We should anticipate that Morones will be speaking up for Mexico, Mexicans, and improved cross border relations for as long as he has breath.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Wonderful piece to be shared by all. We should have more people like Enrique in this world.

Rogelio Quesada

Attorney Emeritus