By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Before Mathew Marko became a Conservative rabbi and before Shoshana McKinney became the executive director of Tikvah Chadasha (New Hope) Uganda serving impoverished Jewish women and children with disabilities in Uganda, they were fellow congregants at Mishkon Tephilo (Tabernacle of Prayer) in the Venice Beach neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Marko went on to earn his rabbinic ordination at American Jewish University in Los Angeles and serve six years as the rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel in Greenville, South Carolina, before becoming senior rabbi at Tifereth Israel Synagogue in San Diego on July 1, 2022. McKinney, who had been born to African-American parents who were Jews by choice, fell in love and married Kirya Israel, a tall Ugandan civil engineer, and together they are bringing up their son, Dovid Avraham, in a village of the Abayudaya (People of Judaism) near Mbale in eastern Uganda.

McKinney and Rabbi Marko renewed their friendship over the August 11-13 weekend, when McKinney served as Tifereth Israel Synagogue’s scholar-in-residence. She outlined what Jewish life is like in the Abayudaya villages, covering Jewish holiday and life cycle observances, and told of the efforts her foundation is making to help impoverished families and children with disabilities.

She related to the congregation that while she was in Los Angeles she became a fan of Uganda’s first ordained rabbi, Gershom Sizomu, whom she had heard give a lecture. She began to follow the rabbi—who also served as a member of Uganda’s Parliament—on Facebook, occasionally commenting about his FB postings. Kirya Israel was another avid reader of Rabbi Sizomu’s FB page, and he began to take notice of what McKinney was writing. They struck up an independent correspondence and visited each other’s countries during their courtship. Sizomu officiated at their wedding.

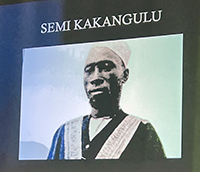

In 1917, General Semi (also Semei) Kakangulu, who had many followers, decided that the Anglican religion preached by missionaries in the then-British colony did not conform with the Scriptures he read in what Christians called the Old Testament. On the other hand, he determined that the Jewish people did follow those laws. He decided that he too would be a Jew, as did his followers. With what at first was a rudimentary knowledge of Judaism, he and his people began to practice it, importing guest rabbis to teach them more. The religion flourished, having today approximately 6,000 adherents, despite the period between 1971 and 1979, when the dictator Idi Amin banned Judaism from the country, making it illegal to wear a kippah, or to place a mezuzah on a doorpost or to have any identifiable Jewish institutions, including even cemeteries.

This caused the Abayudaya to practice secretly in each other’s homes, and children learned their Hebrew while spinning dreidels, making it seem as if they were simply playing a game, according to McKinney. The Jewish community had two causes for happiness during that era. First, when Israelis rescued the hostages that had been taken by terrorists to Uganda’s Entebbe Airport in 1976, and second, when Amin was toppled in 1979 by combined Ugandan and Tanzanian forces and went into exile in Saudi Arabia.

McKinney said while antisemitism was Amin’s policy, that hatred found no resonance at the grassroots level. There is little or no antisemitism in Uganda today, she told the congregants at Tifereth Israel Synagogue. Unlike the congregation where she was speaking, synagogues in Uganda need neither locked gates nor armed guards, she said.

During a slideshow on Sunday morning, Aug. 14, McKinney showed pictures of some of the natural wonders and animals of eastern Uganda, as well as of some of the crops that are raised in that country. She said green peppers are a popular crop among farmers because “they don’t take long to bear fruit and there are many harvest cycles throughout the year. … If you have smelled a pepper, imagine turning up the volume of that smell.” Her father-in-law grows corn, which has a “fruity floral” aroma, she said. “The corn in Uganda is not the soft sweet yellow kind; it is the hard white ones, which you might use for grits or corn tortillas. … Sorghum is a grain they use for syrup and dumplings.”

Looking ahead to upcoming Jewish holidays, she said during Rosh Hashanah the most popular place to attend services is the Moses Synagogue in Nabugoye, which is Rabbi Sizomu’s home base. “People who belong to other synagogues will go to the big synagogue for Rosh Hashanah, like a pilgrimage, I guess,” she said. Her husband and other men wear a kandu, which was adapted from the thawbs worn by men throughout the Arab world. “It has the look of a kittel, so the Ugandan Jews have appropriated the kandu into their dress for Rosh Hashanah,” she said.

The shofar used during the service “is made differently from most of the ones you have seen here,” she commented. “One of the biggest differences is that it has a hole on the side, so it blows a very high pitch and very evenly.”

In her village, there is a competition who can build the best sukkah. She, her husband and son live in home that was built inside a family compound, owned by her father-in-law. “On our land is a cocoa tree. We use the pods and mangos to decorate the sukkah,” she said. “Sukkah decorating is popular; there is a contest who can build the best one that is well decorated. It is covered mostly with banana leaves, and it has to have some style, some flair, and a good structure. Whoever wins gets bragging rights for the year.”

For Chanukah, “we have those big sidewalk chalks and we get the kids drawing pictures of menorahs and Magen Davids,” McKinney related.

The most popular holiday in Uganda, and here in the U.S. as well, is Passover. Chabad in Uganda’s capital of Kampala, about a five-hour drive from her village, supplies some matzo and others are baked by locals who practice for several days to make sure their matzo is kosher, baked for exactly 18 minutes.

McKinney said on her family’s seder plate, she has among other ceremonial items a green vegetable that can double as karpas; a chicken bone (instead of a lamb bone), an egg, and an orange. She introduced the orange to honor women rabbis in accordance with the American legend that one male rabbi scoffed at the idea of women ever being allowed on the bimah of a synagogue. According to the legend, that rabbi said a woman belongs on the bimah like an orange belongs on the seder plate.

Currently, she commented, an Abayudaya woman is studying for the rabbinate at a Reform Judaism seminary. Why didn’t she study at a Conservative congregation? someone asked from the audience. McKinney said there were a variety of factors, including that the rabbinical student was offered a full scholarship at the Reform seminary. Currently there are no Reform congregations in Uganda, McKinney said, so it will be interesting to see if and when the student becomes Uganda’s first female rabbi, what impact she will have. McKinney said there are a mixture of Orthodox and Conservative congregations in Uganda. She said she and her husband worship at a traditional congregation, where she sits in a women’s section.

Turning to life cycle events, she said that a typical Ugandan engagement party will see bridesmaids in matching dresses ceremonially carrying into the room “baskets of fruit, blankets, vases and all kinds of housewares that the couple will need…. It is all about giving the bride’s family gifts; one person even came with a basket of laundry soap.”

She showed some photos of her own wedding. She and Kirya stood under a tallit that was held up by sugar canes. There were the traditional ceremonies of seven circles, drinking of the wine, exchange of rings, and the breaking of the glass under the groom’s foot. After the ceremony, “we eat the chuppah – we eat the sugar cane. … I was called on to serve the sugar cane. The bride demonstrates her hospitality by taking a tray of the cake or the sugar cane to the guests. It is also considered good manners for women to curtsy to elders, so every time I met an elder, I had to go down to the floor.”

Brit milah (circumcision) is done by a mohel, of which there are a few in Uganda. During the ceremony, onlookers standing at a respectful distance, sing a soft, soothing song, ending it, when the operation has been completed, with the Hebrew words “Baruch Haba, Baruch Haba!” (Blessed is the one who arrives!)

Turning to issues of daily life, while English is the official language of Uganda, some people also speak their tribal languages. She said her father-in-law has taught her some useful phrases to speak to her young son in the Lusoga language such as “What do you want to eat?”; “Stop doing that!”; “Go take a shower”; “Stop fighting!”; and “Go to bed!”

Families who want their children to attend Jewish schools must bear the cost of room and board, said McKinney.

There are no supermarkets where she lives, so shopping means going to the individual stalls at a market place and bargaining with each vendor for the best price. She said that it can take all day talking to the tomato guy, and the onion guy, and the people at the other stands. She said when she bargains with the vendors she brandishes an amount of money, asks what they will give her for that much, then looks at them sideways when they answer. “Is that the best you can do?” she asks.

McKinney has a driver’s license in the United States, but is reluctant to drive in Uganda, because they follow the British style of driving on the left side of the road, and they do it too fast. Also, she said, the roadways have too many potholes.

Turning to the work of her Tikvah Chadasha Uganda foundation, McKinney told of a woman who attends her synagogue who walked an hour each way to pick green peppers or corn. A widow with 12 children and six grandchildren, for her day-long labor she earned only $2. Whenever there was a community meal at the synagogue, she made certain to bring all the children—so dependent was her family on the food that the synagogue could provide.

“We knew we had to do something to change her life and so we sponsored a chicken farm for her,” McKinney said. “At her home, she had an abandoned shed. We plastered over a section of the shed to keep the baby chicks so they wouldn’t be exposed to sand or other particles they could confuse with food. We added solar panels so that the chickens will have some light to see where the food is. We got those water dispensers and feeding troughs” and even galoshes or “muck boots” for the woman to wear inside the coop. “We got the feed and the baby chicks” and because they did so, “we triple her income every month and she works at home – no more walking an hour to the fields. Nothing that we do changes lives faster than women’s businesses, night and day. They sell the chickens. They get income every month. It is a long-term solution. One of the kids is able to go to school. They can deal with it if someone gets malaria. They can deal with anything life throws their way. There is sufficient food in the house.”

McKinney’s father-in-law has raised hundreds of thousands of chickens, and her brother-in-law consults for agribusinesses about raising chickens, so McKinney received expert advice as she began the program. The Foundation runs a training program for women who want to raise chicks for later sale at market when they are full grown and tasty. The profits not only allow replenishing the women’s supply of chicks but also provides financial security for the family. To build such a business from scratch costs about $1,300 U.S., she said, with sponsors always welcome.

Similarly, the Foundation solicits donations and sponsorships for its programs on behalf of children with disabilities.

“Disabled children in Uganda really have an uphill battle,” she said. “In Uganda, a disability is looked at as a curse on the family; the superstition that it is bad luck. It is not looked at like a disease or a medical condition.” Some families even hide their children with disabilities, she said.

“There are schools for disabled children,” McKinney added. “Many parents don’t know what resources are available to them. We want to get the kids into the schools … What we want is for all disabled kids to be self-sufficient when they reach adulthood.”

As Uganda has only a limited number of seats in government schools, opportunities for children with disabilities are expensive—often well beyond the reach of many Ugandan families. There are three terms in a school year, with each costing $800. With the help of sponsors, Tikvah Chadasha Uganda underwrites those costs, which include room and board for the children.

The foundation accepts donations large and small. McKinney may be reached by email TikvahUganda@gmail.com or via Post Office Box 1489, Mbale, Uganda 225.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Thank you for writing this interesting and very informative article! Shoshana is a lovely person.