Editor’s Note: This is the 14th in a series of stories researched during Don and Nancy Harrison’s 50th Wedding Anniversary cruise from Sydney, Australia, to San Diego. Previous installments of the series, which runs every Thursday, may be found by tapping the number of the installment: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

By Donald H. Harrison

DUNEDIN, New Zealand – Founded by Scots in 1848, this city on New Zealand’s South Island boasts the southernmost synagogue in the world, and thus for a Jewish traveler, the two cultures are inextricably intertwined.

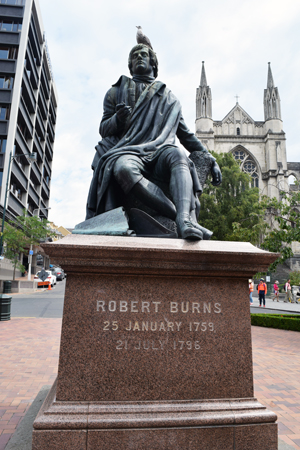

Robin Lamont, a member of Dunedin’s small Jewish congregation, met us at the “Octagon,” an area of downtown Dunedin that is dominated by a statue of Scotland’s favorite national poet, Robert Burns. People who know Burns’ work even casually may sing his “Auld Lang Syne” on New Year’s Eve, not necessarily understanding the meaning of the words, or perhaps too caught up in celebration to care. Just think of the Scottish phrase, “Auld Lang Syne,” as meaning “for old time’s sake.”

Less well known is the fact that Burns, who lived during the 18th century and was an admirer of both the American and French Revolutions, on one occasion decided that the 90th Psalm, attributed to Moses himself, needed a rewrite. So that’s what he did in a work called simply enough “First Six Verses of the Ninetieth Psalm.”

To appreciate his effort, we need to reacquaint ourselves with the original. As translated from the Hebrew in the Stone edition of the Tanach, Moses had this to say in the first six of the 17 verses of Psalm 90:

1. O Lord, You have been an abode for us in all generations, 2 before the mountains were born and You had not yet fashioned the earth and the inhabited land, and from the remotest past and to the most distant future, You are God. 3. You reduce man to pulp and You say, ‘Repent, O sons of man.’ 4. For even a thousand years in Your eyes are but a bygone yesterday, and like a watch in the night. 5. You flood them away, they become sleeplike; by morning they are like grass that withers. 6. In the morning it blossoms and is rejuvenated; by evening it is cut down and brittle.

Now, here is Burns’ version, as transcribed on the encylopedic website www.robertburns.org

O Thou, the first, the greatest friend

Of all the human race!

Whose strong right hand has ever been

Their stay and dwelling place!

Before the mountains heav’d their heads

Beneath Thy forming hand,

Before this ponderous globe itself

Arose at Thy command;

That Pow’r which rais’d and still upholds

This universal frame,

From countless, unbeginning time

Was ever still the same.

Those mighty periods of years

Which seem to us so vast,

Appear no more before Thy sight

Than yesterday that’s past.

Thou giv’st the word: Thy creature, man,

Is to existence brought;

Again Thou say’st, “Ye sons of men,

Return ye into nought!”

Thou layest them, with all their cares,

In everlasting sleep;

As with a flood Thou tak’st them off

With overwhelming sweep.

They flourish like the morning flow’r,

In beauty’s pride array’d;

But long ere night cut down it lies

All wither’d and decay’d.

Call it chutzpah, or call it brilliance, but anyone who can rewrite Moses – and arguably make his words sound better and even more reverent – has a lot about him to admire. If only the pigeon that roosted atop Burns’ sculpted head could understand how inappropriate was its choice of resting place.

As an engraving on the pedestal beneath Burns’ statue notes, the poet was born January 25, 1759. Worldwide, that date is celebrated as Robert Burns Night, when his life and works traditionally are remembered along with a serving of haggis. Because New Zealand is one of the largest producers of sheep, that is not a difficult dish to obtain, especially in Scottish inspired Dunedin. According to Wikipedia, it is made from the heart, liver, and lungs of a sheep, minced with onion, oatmeal, suet, spices, and salt, and traditionally cooked in the animal’s own stomach. Of these, only suet—the hard fat around the kidneys and loins of a farm animal—is problematic for the kosher chef, but this ingredient is easily substituted. Today, one can find kosher haggis on sale in Scotland, and, one assumes, it is not unknown among the poetry-loving, observant Jews of New Zealand. It has been compared to kishkes.

It is not mere happenstance, nor love of good poetry, that Burns is so celebrated today in Dunedin. As a plaque near the statue makes clear, “The poet’s nephew, the Rev. Thomas Burns, was a co-founder of the Otago settlement (1848) and Presbyterian minister of Dunedin’s First Church.” Otago is the name of the region on South Island which includes Dunedin.

If we Jews really be “People of the Book,” then how can we not appreciate the fact that there is a Writers Walk leading in semi-circular fashion from the Burns’ statue? Bronze plaques set into the pavement honor writers with a connection to Dunedin, including the Jewish poet Charles Brasch, who founded Landfall Literary Magazine in 1947. Each plaque comes with a quotation from the author that evokes Dunedin. For Brasch, the quotation from his “Indirectons” read: “I grew to know most of the country about Dunedin in all its variousness. It impressed itself on me so strongly that it seemed to accompany me always, becoming an interior landscape of my mind or imagination, unchanging, archetypal …”

Brasch and our Dunedin host Robin Lamont were related through the Hallenstein merchant family. According to an article in the Spring/ Summer 2018 issue of Western States Jewish History, written by the late Dunedin merchant and Jewish communal leader Ted Friedlander, who was a relative of Brasch’s, “It is a known secret in Dunedin that Charles and his cousins Dora, Mary and Esmond de Beer were the endowers of the trust which established the Mozart Fellowship in Music; the Burns Fellowship in Literature, and the Hodgkins Fellowship in the Arts at the University of Otago.” Fellows are provided with an office and a year’s salary to be creative during their University of Otago tenure.

Further, reported Friedlander, “Brasch was an early supporter of such indigenous New Zealand artists as Colum McCann as well as such great literary figures as Janet Frame. For many years he enabled the University Library to purchase every poetry book published in England and he bequeathed his extraordinary book collection to the University Library upon his death. Though his meticulous journals and collections of letters and family papers were embargoed for thirty years following his passing in 1973, they have recently been opened to the public, and have proven to be a treasure trove of knowledge on the history of the Hallensteins as well as the Jewish community of the Southland.”

Both Friedlander and Brasch could trace their lineage—Brasch directly and Friedlander indirectly–back to Bendix Hallenstein, who had served in New Zealand’s Parliament from a Queenstown district, before moving in the late 19th century to Dunedin, where he and his brothers established a clothing factory, which evolved into the Hallenstein Brothers chain of retail stores. From that chain’s profits, the Hallensteins invested in the New Zealand department store chain known as D.I.C.

When Nancy and I made preparations for our cruise aboard the MS Maasdam, which we knew would take us to Dunedin, we had arranged by email to meet with Friedlander to learn more about the city’s Jewish history. Unfortunately, by the time we arrived, Friedlander, a nonagenarian, had died. His daughter, Robin Lamont, insisted on escorting us around the city, as perhaps her father might have done, even though we did not wish to impose upon her during her year of mourning.

Among the places she escorted us to was Olveston, the 35-room mansion built between 1904 and 1906 for David Theomin, a leader of Dunedin’s Jewish community who made his fortune importing pianos for music-loving New Zealand. He named his mansion after a village in which he had enjoyed childhood holidays. Lamont occasionally has served as a docent at the mansion, and her brother, George Friedlander, has been more intimately involved in the preservation of the home, now owned and operated by the City of Dunedin. George served as president of the committee that is involved in promoting the mansion as a home of the arts. Robin’s and George’s father, Ted Friedlander, was instrumental in persuading the city to accept the mansion after David Theomin’s daughter, Dorothy, willed it, along with a fund for maintenance, to the city upon her death in 1966. At first, the city didn’t want to take on the responsibility, but after a public relations campaign to save the mansion, it was persuaded to do so.

I asked if there was much Judaica in the mansion. “Quite a bit,” she answered. “The dining room table is set for Shabbat.”

According to Ted Friedlander’s memoir, the mansion was “filled with a sizeable collection of European and Oriental treasures collected during the Theomins’ extensive European travels.” David Theomin was a patron of the arts, being a contributor to the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, an office-bearer in its society, and a quiet supporter of young artists, among them Frances Hodgkins. He had a long association with the Royal Dunedin Male Choir.

Another stop on the Thursday of our visit was outside the locked Beit Israel Synagogue, which today is housed in a simple bungalow as a result of a diminishing Jewish population since the congregation’s heyday in a large building in downtown Dunedin. Magen Davids still can be seen on the windows of the former Grand Synagogue, but the building today is used for secular purposes.

Lamont said that intermarriage is quite common in Dunedin. Another handicap to Jewish religious continuity is the fact that the congregation hasn’t had a rabbi in many years, but instead has depended on local lay leaders. She said she went to Hebrew School as a child, “but didn’t listen and didn’t learn,” and that her husband David’s and her children identify less as Jews than the previous generation. It is not uncommon for Dunedin children to move to Auckland on New Zealand’s North Island in search of greater opportunity, noted Lamont.

Asked about growing up in Dunedin, Lamont said what she remembered most about her childhood was spending summers at the nearby beach town of Wanaka, as well as having another family residence in the Central Otaga town of Karitane, about a 3 ½ hour drive from Dunedin. “It has a lake, and it’s beautiful up there,” she said. “In the spring, there are all these wonderful colors; and in this time of year, all the summer fruits.”

As she reflected upon it, she suggested that while she was growing up her lifestyle was “more Kiwi than Jewish.” However, she said, she takes pride in being Jewish, because “those are my roots.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

The Bible continues to intrigue and inspire writers: take my own sonnet collection, “People of the Book” (on the web link), which gives voice to its marginal characters, like Lazarus, Ruth’s sister and Eutychus.

Pingback: A posthumous salute for Rabbi Katz of Wellington | San Diego Jewish World

Pingback: Those special touches on a cruise ship | San Diego Jewish World